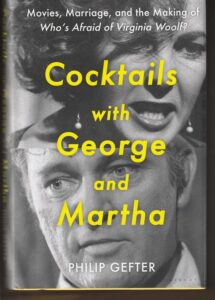

There are two major characters in Philip Gefter’s Cocktails with George and Martha: Movies, Marriage and the Making of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

One is the four-actor play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, written by Edward Albee that opened on Broadway on October 13, 1962. The other — a much larger character — is the movie of the same name, based closely on Albee’s play and directed by Mike Nichols, which premiered on June 21, 1966. Indeed, Gefter’s book is a biography of the movie.

Other important characters are Albee, Nichols and Ernest Lehman, the scriptwriter and producer of the movie.

Surprisingly, two lesser characters are Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, the George and Martha of Gefter’s title and the George and Martha of the movie.

That’s odd to say since the two married actors — perhaps the most famous couple in the world in the 1960s because of the scandalous affair that started their relationship and the lavishness of their personalities and lifestyles — appear on perhaps as many as 150 pages of the 290-page book.

So, let me explain.

“So Brooks Brothers”

“So Brooks Brothers”

The first 47 pages of Gefter’s book are devoted to Albee — to his unhappy childhood and how it shaped him, to his homosexuality and his circle of literary friends and lovers, to his writing of the play, and to the production of that work under his close supervision.

Lehman plays an outsize role in the remaining 200-plus pages of the book, even though he was certainly a less glamorous figure than Taylor and Burton and Nichols, or, for that matter, than Sandy Dennis and George Segal, the two other actors in the movie, portraying Nick and Honey.

A prolific and highly successful screenwriter, Lehman wrote the movie’s script, much adjusted by Nichols back to Albee’s original words, and was a neophyte as the producer of the film. Of course, as a movie director, Nichols, a Broadway and Off-Broadway director of note, was a neophyte as well.

On the set of the film, Lehman was a pretty colorless figure, especially compared to Taylor and Burton and Nichols. Taylor, in fact, once said to him, “You’re so Brooks Brothers.”

“A daily production chronicle”

In Gefter’s book, however, Lehman gets a great deal of time on stage for one reason, his concern for his legacy in film history. Gefter writes:

Further proof of Lehman’s intentional legacy-building exists in the form of a daily production chronicle he kept during the entire process of making Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? This methodical account of daily events was aimed clearly at posterity….

Lehman’s documentation is a systematic chessboard-like description of the daily activities, obstacles, minuscule dramas, and protracted sagas throughout the production of the film, commencing soon after the arrival of Nichols in Los Angeles.

At the end of each day, Gefter relates, Lehman would get in his Cadillac sedan and, on his drive home to Brentwood, speak into a Dictaphone, “recounting the events of the day relevant to the production, monitoring his role as producer-screenwriter, and expressing his feelings.” The next morning, his secretary would transcribe his words as the next installment of a continually growing real-time document of the experience.

Lehman and Nichols

Time and again in Gefter’s account of the progress of the film’s production, he trots out Lehman’s observations and information from this daily diary.

This was a godsend for Gefter, as a researcher and writer, providing him with a skeleton of you-are-there details about the specific events that were taking place, and a touchstone against which to present the memories of that time from Nichols and others as recounted in interviews and memoirs.

While Gefter’s book is a biography of the movie, Lehman’s diary is a running color commentary on it as it happened.

As a reader, I couldn’t help thinking that, without the presence of his diary, Lehman’s role in Gefter’s book — in anyone’s memory or story of the production, to be honest — would have been much smaller. Nichols would have overwhelmed him in what participants remembered, leaving him as something of a stick figure. Maybe he realized this — hence, the Dictaphone.

When it comes to Nichols, Gefter is clearly fascinated by the director’s intelligence, taste, confidence and insecurities, giving a great deal of attention to his back story and the details of his decisions and actions in making the film.

The film is the main character of Cocktails with George and Martha, and, in the complex ways of filmmaking, Nichols was, by far, the most important person to bring it into existence.

Liz and Dick

So, Gefter takes in-depth looks at Albee, Lehman and Nichols. He gives necessary but passing attention to Segal and Dennis.

And then there are Burton and Taylor.

Reading Cocktails with George and Martha, I’m struck by the realization that, in the not too distant future, the whole Dick and Liz thing will fade into insignificance.

As a teenager in the 1960s, I remember all the hubbub about the couple, about their marriage and divorce, their remarriage and redivorce. They were a kind of world royalty, acting in the flamboyant and shocking ways of many kings, queens, princes and princesses over the centuries. In the Western world, you had to be a hermit not to know of them — indeed, not to be inundated with regular updates about their doings and over-doings.

Their stories as a couple and as individuals have been told and retold and retold for more than half a century. This meant that Gefter couldn’t go very deep into who Burton and Taylor were without possibly boring his readers or having the two overwhelm his book. It also meant that he could take writerly shortcuts, making passing references to their backgrounds and careers and love lives, relying on his readers to fill in the blanks.

The result is a story of the movie told mainly from the point of view of Nichols and Lehman. Taylor and Burton enter the story only to the extent that they are interacting with those two and doing their actor’s work in the film.

Neither Taylor nor Burton wrote memoirs. Neither did they write anything about their experience in the filming of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? — about what it was like for them as individuals and as a couple playing an emotionally violent, dysfunctional couple. They appear in Gefter’s book based on what other people had to say about them during and after the production.

Too much side talk about marriage

Gefter’s book is a pleasant, respectful book about a movie that he clearly regards with great reverence — maybe too much.

I say that because Gefter goes to great lengths to argue that the play and the movie have a great deal to say about marriage and had a great deal of influence on American culture.

There might be some truth to that, but, in his book, it is only Gefter making these assertions. It might have helped his case to have brought in some other voices about the significance of the play and movie.

As it is, he works too hard, delving into the psychology of marriage to an extent that is unnecessary and, in fact, distracting for the reader.

The greatness of the play and the movie — and what they have to say about marriage — are there for anyone to experience. They can speak for themselves.

All of Gefter’s side-discussions about marriage, particularly in his long epilogue, could have easily been trimmed from his book, and it would have been better for it.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.29.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.