In the epilogue of her astute, significant and multi-dimensional Cuba: An American History, Ada Ferrer focuses on the work of sculptor Teodoro Ramos Blanco.

She writes that, during the course of a long career, Ramos Blanco “created monuments to many people who have appeared in the pages of this book,” including:

- Placido, the poet and man of color executed for his antislavery work in the mid-19th century.

- Antonio Maceo, a general in the Cuban wars for independence from Spain, killed in action in the 1890s.

- Jose Marti, the poet and nationalist known as the Apostle of Cuban Independence, also killed in action in the 1890s.

But Ramos Blanco didn’t limit himself to famous people. She writes:

[He] loved to carve anonymous people, the kind of people who might have walked by his monuments every day. In wood and bronze and marble, he carved beautiful statues to them, too. One, titled simply, The Slave, won first place at the World’s Fair in Sevilla in 1929; another called Negra Vieja (Old Black Woman) sits in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Another was given by the sculptor to Havana’s National Museum of Art. It’s titled Interior Life, and it’s the head and face of a black woman carved in white marble.

The woman’s face is serene, contemplative; her eyes are closed. She could be one woman thinking about something that happened the night before. She could be any of the millions of women whose lives overlapped with the more than five centuries of Cuban history in this book.

History beyond the rich and powerful

Ferrer, a Cuban-American historian specializing in Latin America at New York University, spends most of this four-page conclusion to her book on the work of Ramos Blanco because it mirrors her own efforts as an historian.

In the past, history was owned by the rich and powerful. It was the story of kings and titans. It was, as that truism has it, written by the winners. It was about policies and governments, about decisions by important people or those who would be important.

For wars, it was written from the perspective of generals, a kind of bird’s eye view of the battlefield with thick or thin arrows swooping this and that way on the map. Little regard was given to the soldiers — the hundreds or thousands or tens of thousands of soldiers — who made up those arrows. A general might suffer a loss. The unacknowledged foot soldier would suffer death.

It was relatively easy to write about the generals and the rulers and the power brokers because they left lots of documentation. Much harder to figure out what it was like for the average person who participated in the making of history — the soldiers, the factory workers, the farmers, the servants, the drovers and all the rest.

But, over the last century, more and more historians have taken up the challenge and found ways to recover this aspect of the past. One example is John Keegan’s Face of Battle (1976) which told the story of three major battles — Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme — from the experience of the foot soldier.

“People make history”

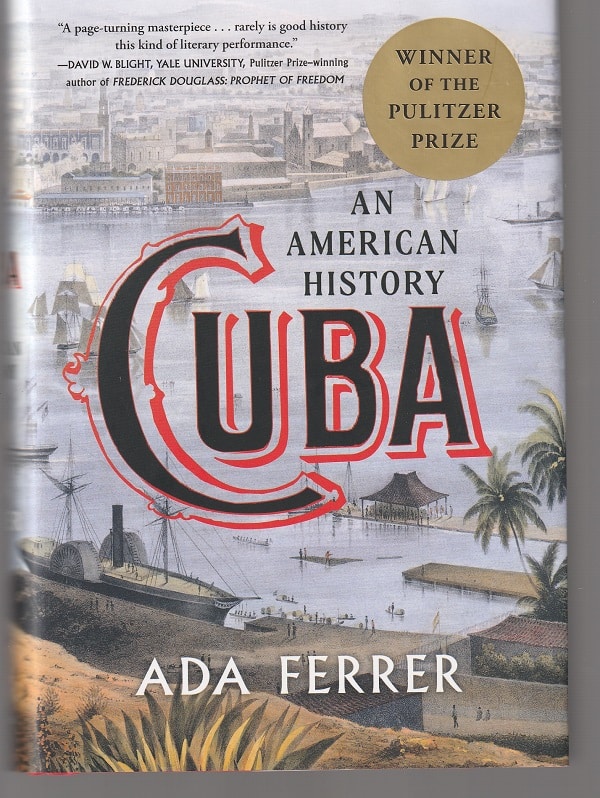

In Cuba: An American History, which won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in History, Ferrer is going several steps further, attempting something much more complicated.

First, she is telling the history of Cuba with an emphasis on its relationship with the United States — and telling the history of the United States with an emphasis on its relationship with Cuba.

Second, just as important, she is telling this history in a multi-level manner, recounting the actions, decisions and policies of the leaders of governments and of rebellions while also detailing the words and actions and experiences of everyday people.

Written history, Ferrer writes, can be told as the story of heroes or as an account of “abstract forces — social classes or groundbreaking ideas or economic structures.” It can be seen as “a current between sweeping transformations and stubborn continuities” with events inelegantly layered upon each other.

But if history is all those things, it is also the countless lives that are nested in its sway. Consider all the people who may have lived at some point during Cuba’s long history, from before the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the present. Every one of those lives embodies and condenses the history that made it.

The large-scale events of history — conquest, enslavement, revolution, war — ripple through individual lives, shaping them like so much stone or clay.

As history makes people, so do people make history, reworking it, day by day, creating meaning of the world around them, often acting in ways that tend to fit but awkwardly in the categories of epic history.

“On a more human scale”

As I said above, it’s easy to get a lot of information about Fidel Castro or President James Monroe and about their actions and decisions. It’s much harder to get a feel for how an everyday Cuban felt and acted at any point in the history of the island — but it’s crucial, Ferrer writes, to try.

As we ponder the sweep of centuries, it is important to pause at those lives, not just to invoke them, but to endeavor to grasp history through their eyes, as if walking among them, to paraphrase the nineteenth-century Haitian historian Emile Nau.

It is an impossible endeavor in many ways — we cannot simply slip into someone else’s place. But the attempt itself is essential. It has the potential to disrupt, if fleetingly, our assumptions about people, places, and pasts. It nudges us to glimpse the world differently, to grasp history on a more human scale, perhaps even to see ourselves through the eyes of others.

Nose rings?

For instance, race is an important thread in the history of Cuba, impacting virtually ever issue of a civil society — even a revolution.

During one of the wars for independence, a rebel army from the east end of the island was battling its way to the western portion, and rumors were swirling that the predominately Black troops of the rebel army wore a ring in their nose. Ferrer describes this and the thinking of those in the west regarding such stories:

It might be true — eastern Cuba was far away, its customs possibly different. But the notion of Black rebels with nose rings also sounded like a government lie.

Jose Herrera (nickname Mangoche), a fifteen-year-old sugar plantation worker in Havana province and the grandson of an African-born midwife, debated the issue at length with his friends. Unable to contain his curiosity, one of them journeyed east from Havana to get a glimpse of the invading army before they arrived.

He came back with an authoritative, eyewitness answer: he had seen the rebels, and they did not wear nose rings.

A deep richness

This is a story that’s about more than nose rings. It’s about the way the government was trying to use race to drive a wedge between the rebels and the Cuban people. It’s about how racial prejudice can be fed by emphasizing oddities, like the supposed nose rings.

And, even more, it’s about how a group of average Cuban teens dealt with the rumors. By getting eyewitness evidence.

Such anecdotes add a deep richness to Ferrer’s extraordinary account of Cuba’s history, an account that deftly brings together many layers and many threads and many perspectives.

It is an account about famous names and obscure citizens, about a small island in the shadow of a mammoth nation, about a society of Blacks and Whites in an uneasy balance, about corrupt leaders and idealistic martyrs.

If only all history-writing could be this good.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.27.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.