One of the opening paragraphs of Sam Weller’s short story “All the Summer Before Us” is this:

“We were eighteen, me and Dave and Bill; childhood friends on the cusp of adulthood. On a silent country road we had discovered an old concrete pipe factory out amidst the darkness and the corn stalks that would, in weeks, be knee-high by the fourth of July.”

These three boys in the green fields of western Illinois lead a rural life of walking and exploring, out past the new subdivision. And, that night, at the concrete pipe factory, they decide to climb the rusty ladder to the roof of the four-story silo-like tower.

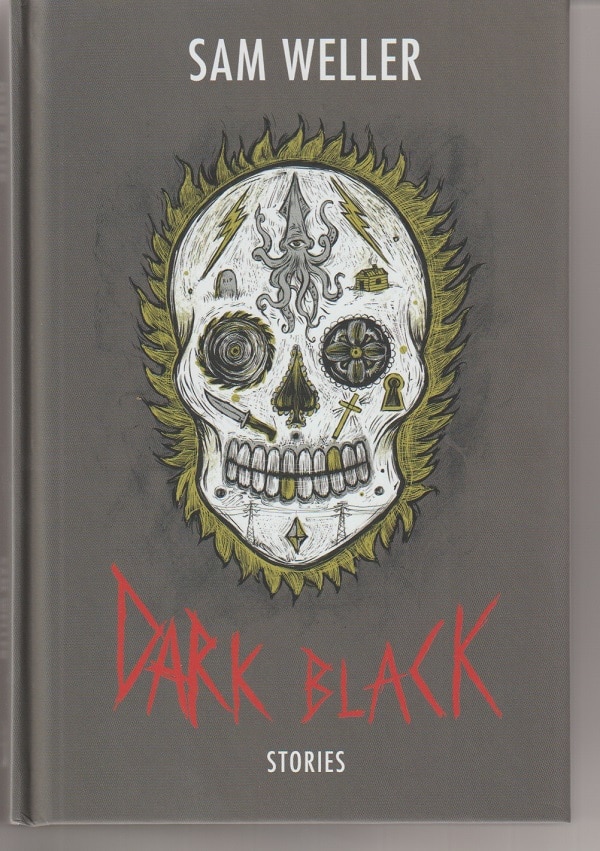

This story is in Weller’s new book Dark Black which his publisher calls “haunting.” So, you might be tempted to expect that something horrific awaits the boys at the top. Or spooky. Or morbid. You’d be wrong.

Weller, a longtime Chicagoan who teaches creative writing at Columbia College, is best-known for his authorized biography The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury, published in 2005, as well as two other books on Bradbury. In fact, Bradbury, the author of the novel Fahrenheit 451 and short story collections The Martian Chronicles and The Illustrated Man, even makes an appearance in Dark Black, Weller’s first book-length fiction.

“Six snow cyclones”

The 20 stories in his collection, 12 of which have appeared in various journals, deal with people living generally mundane lives who come face-to-face with something strange. Such as a little girl lost in a forest, and a sea monster’s siren call, and a face in a bag of blood, and a crowd of dancing snow swirls that seem like cyclones.

Those last show up in the story “Monsters and Angels” in which a man who fled a self-defense killing in Cincinnati finds a home in an abandoned cabin in the prairies of Nebraska. Several nights, he wakes up in the dark to see outside his window “cyclones of snow shape-shifting” in the white-filled dark.

“One night in January, he counted six snow cyclones beyond the cabin, howling, great wings of snow, trying to take flight. At one point, heads emerged, beaked like tremendous birds, wings of white gusting. They looked like phoenixes or maddened snow dragons; monsters or angels, he could not decide.”

Mostly decent people

That might strike you as pretty creepy, and it is certainly eerie. Yet, with one exception, none of Weller’s stories deals with strange stuff that is intrinsically wicked. That one anomaly is the story titled “Bose,” the German word for “evil,” and it does feature a reference to a Nazi doctor from the past. Even so, the narrative is presented from the perspective of a decent, hard-working, compassionate nurse.

That’s the thing about Weller’s stories. The characters are all pretty much decent people. Yes, the arrogant academic of the first story “Little Spells” is a pompous ass, but, in Weller’s world, even a pompous ass isn’t evil. And he is self-aware enough to recognize that he’s found himself in the middle of a great deal of strangeness having to do with a grisly event a half century earlier.

There’s a temptation in modern America to equate anything strange, anything unexplainable, particularly anything that has to do what might be called the spirit world, as malevolent. Bad things are lying in wait to descend on us and do violence, physically or emotionally.

Maybe, as a culture, we’ve watched too many horror movies. Or maybe modern life, with its threats of terrorism and Covid and nuclear annihilation, is so scary that it’s pushed us to watch horror movies. Whatever the cause, we expect anything strange to be ghastly and violent.

Not so in Dark Black.

Move and act

Weller’s stories are unsettling, but in a stoic way. They are populated by people with good intentions, such as the girl who throws away a yard sale purchase that seems to give her magical power in “The Key to the City” and the reporter who interviews Bradbury and finds out way more than he wanted to know in “Live Forever!”

Standing face-to-face with the strange, Weller’s characters don’t blink. They don’t freak out — well, except for the scholarly prig in the first story. They move and they act, often in a way that tries to make things better or to make a connection where, it seems, one is missing.

And they live with the consequences. That’s what I mean about stoic. They accept the strange, and they accept what happens when they interact with the strange.

They are gentle people, and Weller’s stories are often sweet, even when the central characters end up facing what will change them and their lives forever.

Those three boys who climb up the ladder in the concrete pipe tower will find something strangely wonderful and strangely mundane. They will find themselves.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.25.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.