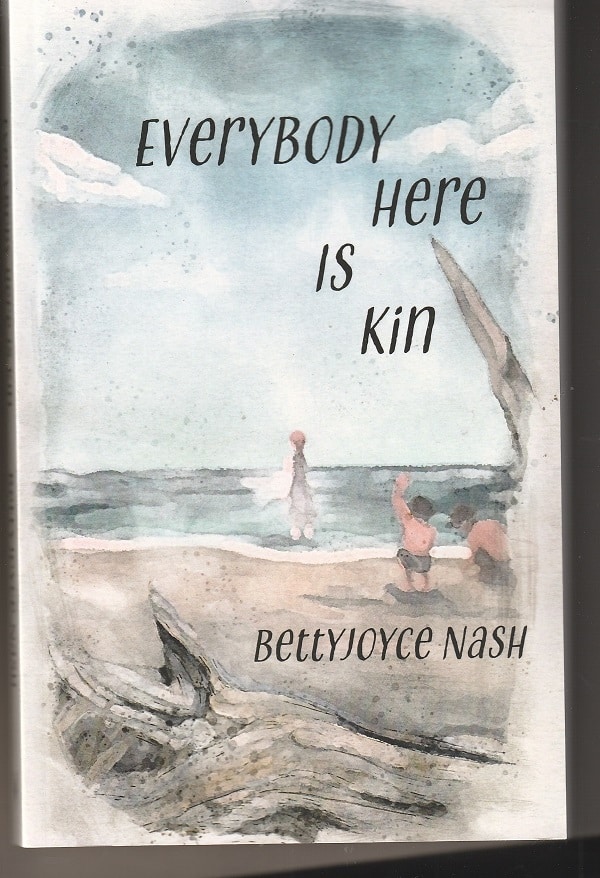

BettyJoyce Nash’s crackerjack novel Everybody Here Is Kin has been described as a coming-of-age tale, but that’s only half of it. It’s also a coping-with-PTSD-after-military-service story.

And, really, it’s a lot more. There’s a reason the title is about “everybody.”

Nash, a former Chicagoan, builds her novel with alternating perspectives. One is in the voice of Lucille Lamb, only a few days short of turning 14 on Labor Day, 2013, as the book opens.

She is intent on getting her mother Naomi, a Detroit nurse on an open-ended leave, to drive her and her two younger half-siblings to Key West to see the coral reef before it dies. Lucille has great worries about the many natural catastrophes that seem to be daily occurrences and those just over the horizon.

She also wants to go to Key West to scatter the ashes of her father, a U.S. military officer who was killed by an IED (improvised explosive device) in Fallujah in 2004, early in the Iraq War. But the fortyish Naomi has stopped at Boneyard Island in Georgia to renew acquaintances with a former boyfriend.

Lucille, Naomi and the little kids — earnest five-year-old Jack and wisecracking seven-year-old Mayzie — are staying at the vintage 1940s Palmetto Tourist Court, managed by thirty-year-old Will Altman.

Will’s haphazard life

Will provides the other storytelling perspective. He knows all about IEDs and Fallujah and the Iraq War. And he knows Boneyard Island since he grew up there. In fact, he even remembers, as a 14-year-old, seeing Naomi and her officer husband, Robert. The island is where they honeymooned. And, as Lucille later realizes, it’s where she was conceived.

Life after military service hasn’t been all that easy for Will. He’s had his problems with booze, and, even more, he’s had his problems with finding a place in civilian life for himself. His first appearance in the novel is when he is out on a date with Belva, a highly competent local leader and another longtime resident of the island.

He’d lurched late into civilian life. This was only his second date since he’d climbed out of the sandpit ten years ago, not counting the uninspired sex with guests at the tourist court he managed.

Will is going about his somewhat haphazard life and Lucille is trying to enjoy her time on the island even as she frets about the environment and about whether she’ll get to Key West when the first of two major turning points in the novel takes place.

Naomi leaves

Naomi goes off with her old boyfriend to a posh resort on another island, leaving a note: “See you Wednesday, I need this, I’m burned out, I’ll text or call. Here’s seventy-five dollars — be careful —.”

Lucille is a very together 13-year-old who is used to taking charge of Jack and Mayzie when Naomi’s working double shifts at the hospital. And she’s used to taking care of Naomi, even back when, as a five-year-old, she ran interference with the social worker who wanted to take her away from her deeply grieving mother.

Still, they are three kids alone on an island that’s not their home, and, well, they start to lean on Will and he starts to enjoy having the three kids to take care of.

Lucille also develops the beginning of a romance with Renaldo, a slightly older teen. And she bonds with Renaldo’s grandmother Queen, “an old woman with hair like dryer lint…with sunken black eyes, her face, a dried dark prune.” When the girl asks if Queen is a title, the 73-year-old woman says: “Believe it or not, girl. Queen was my mother’s name. A turtle queen. I monitor the sea turtle nests on the beach.”

Scattering her father’s ashes

Naomi eventually returns, much later than she’d promised. But then comes the second turning point — Lucille goes off to scatter her father’s ashes in the nature preserve on the island with Queen tagging along, just as the island is about to be hit by Hurricane Louis.

Not everything turns out well in this novel. The hurricane wreaks great destruction. A major character dies.

Yet, Everybody Here Is Kin is a feel-good novel. Nash skillfully shows how each character, from the youngest to the oldest, works hard at coping and on how each character is supported and nurtured by others, as if in a large family.

Families have lived so long on Boneyard Island that many of the residents are interrelated, cousins of some sort.

When a local store owner offers Jack and Mayzie a small job of unloading boxes of potato chips so Lucille can go for a run, the girl isn’t sure what to think. “Go on,” she’s told, “everybody here’s kin to everybody. We look out for each other, after a fashion.”

The kinship of all people

In Nash’s story, it’s not just the island people who are kin to each other.

Everybody Here Is Kin is about the kinship of all people. Her characters cope, as we all do, in complicated, imperfect ways. And they cope best, as we all do, with the encouragement and assistance and affection of those around them.

Even in the face of climate catastrophe, even dealing with grief and trauma and all the joys and sorrows of life, her characters have richer lives because they are together. As we all do.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.7.23

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on XXXXXXXX.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.