Surrender, premeditate nothing, want nothing, neither discern nor dissect nor stare, but rather shift, dodge, lose focus, and — slowing down — consider the only material that presents itself, in its disorder and even in its order.

*

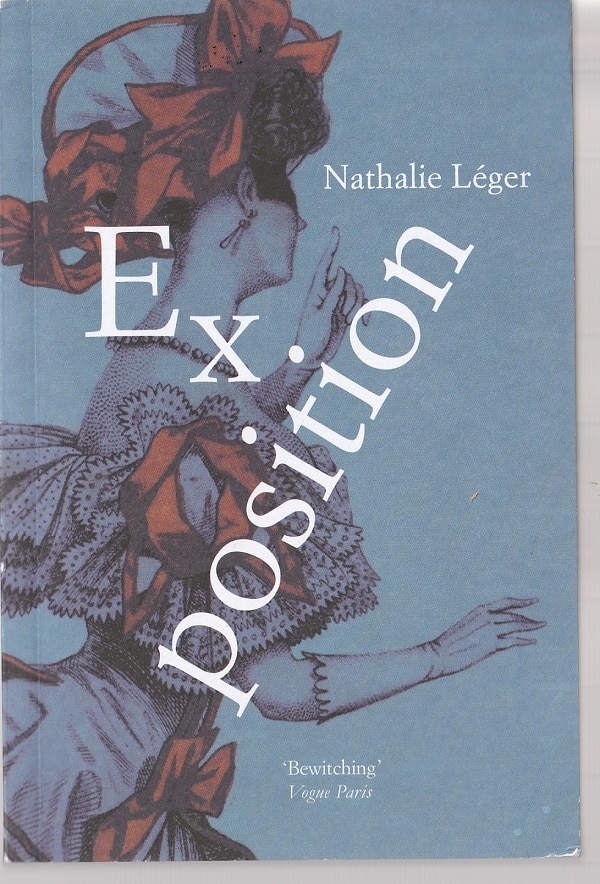

At the start of her luminous 2008 book Exposition, Nathalie Leger makes clear to the reader the need to abandon all expectations at the entryway. This is the first of maybe 150 stand-alone paragraphs in the 153 pages of Leger’s small-format work. To say, “stand-alone” may be misleading since, in some cases, there is some connection between one paragraph and the next. Yet, such connections are, it seems to me, of much less importance than the integralness, the integrity, the unity of each paragraph. Its separateness, isolation — like a photograph among photographs.

*

…of course, she was happy with these homages, but that is not why she had herself photographed, she had herself photographed to construct, under the guise of frivolity, what Poe called “The chamber of melancholy.” To hold on, to silently hold on.

*

Leger — an art curator who has made her name with the publication of this book and two others (Suite for Barbara Loden [2012] and The White Dress [2018]) that together form a trilogy of meditations on the lives of women — suggests that there were perhaps 500 photographs that Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, a noted Italian beauty of mid-19th century France and a mistress of French Emperor Napoleon III, staged and posed for over the course of her life. The photographer was Pierre-Louis Pierson. “This number is practically inconceivable for the era (many more photos than Mapplethorpe took of Lisa Lyon, and maybe even more than Cindy Sherman took of herself).”

*

The dawn of photography could be said to date from January, 1839, when Louis Daguerre sold his daguerreotype method to the French government which, seven months later, presented it to the world, complete with working instructions. The Countess of Castiglione was born in 1837.

*

In the end, and there are many accounts that verify this, she entertained the dream of exhibiting her photos at one of the pavilions of the upcoming 1900 International Exposition….There would have been a poster, and she would have dithered at length over which photo to choose. Pierson would have wanted the one titled Scherzo di Follia, which shows her holding an oval frame in front of her eye, and staring at us through it, a photo that has since become the emblem of photography, though neither he nor she could have known it. But she, she would have preferred a different one, from the same series, the one that shows her magnificent profile, her shoulders bare, and her arm, such a velvety arm, delicately accented by the shadow of a dimple at her elbow…

*

This International Exposition is one of many expositions that fill Leger’s Exposition. She researched the photos of the Countess of Castiglione to determine the centerpiece of a museum exposition that she was to curate although, in the end, the museum did not like her choice of an image of the Countess with a dead dog — too, well, something as her rejection letter reads, in part, “not only does the project not seem in line with the tastes of the audience of our museum, but in addition, abjection does not figure in the image of ourselves which we communicate when we promote our collection.”

*

This exaggerated image of herself, the reliquary for the dead dog, what did she make of it? Wound up in the old fabric of her bodice? Wet with kisses and with tears? She leaned over the filthy thing in prayer, a pulp of dog whose one intact eye persisted like a jewel clipped to the beast. After the intoxication of her beauty, after the ecstasy, she swilled abjection.

*

The photos of the Countess are, of course, expositions inasmuch as she is exposing her body, face, however she has dolled herself up, to the camera lens, and the film of the camera is exposed to the light of her and the scene she embodies in the room she is in. But they are not the only photos, expositions, that Leger contemplates. There are the photos of her mother and of herself.

*

The first photo of me, the one I call the first, I’m eight or ten years old. You can only see my face. It is emerging from a hole in the greenery of a shrub hedge where we built wooden huts. I look at the lens fixedly, as if I were looking at something else.

*

Exposition is a book about seeing and being seen, about creating an image of yourself as the Countess does and about being created as a flat rectangular image by the workings of the camera and the photographer. Leger’s father, unfaithful to her mother, was a photographer.

*

The woman, the other woman, appeared. She glided up to the iron railing, stretching, she turned rapidly, stopping, turning back, coming and going, her gestures entirely addressed to one corner of the shadow of the French door she had just emerged from. She made a little imploring sign and a man appeared in the frame. It was my father. Knees bent, face contorted, eye glued to the camera that my mother have given him for his birthday some days before…I saw them slip along the terrace, careful not to make a noise, laughing silently; then the woman hoisted herself up a little on the railing, the rounded iron of the rail pressing into her thighs, her dress pulled open a bit, they’d stopped laughing, a gravity, something had collapsed between them, my father turned his back to me but I could tell that something had changed, the woman stopped smiling, her face had become thick, her gaze elusive, her mouth seemed enormous and malformed to me, he was still photographing, the dress fell, he kept advancing and she wrapped her legs around his lower back, took the camera from his hand, quickly wound it and, her arms around my father’s neck, body clinging to him, she aimed over his shoulder as if she were photographing the empty terrace behind him.

*

Days later, on her nightstand, set there while she slept, Leger found the photo, just her face, “emerging from a hole in the foliage where we made the little forts.”

Patrick T. Reardon

3.8.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.