And when he finally gets to heaven, after spending 30 years meandering the Universe and then racing a comet, Captain Elias Stormfield of San Francisco (size 13 halo) finds out that a lot of his preconceived notions and a lot of what generations of preachers have told him are just plain wrong.

He bumps into Sam Bartlett “who had been dead a long time” and acknowledges that his first day in heaven has seemed pretty boring. Sam straightens him out:

“People take the figurative language of the Bible and the allegories for literal, and the first thing they ask for when they get here is a halo and a harp, and so on. Nothing that’s harmless and reasonable is refused a body here, if he asks it in the right spirit.”

So everyone gets a halo and a harp, and, for about a day, they do a lot of singing and such. And then they get wise.

“They don’t need anybody to tell them that that sort of thing wouldn’t make a heaven — at least not a heaven that a sane man could stand a week and remain sane….

“Singing hymns and waving palm branches through all eternity is pretty when you hear about it in the pulpit, but it’s as poor a way to put in valuable time as a body could contrive. It would just make a heaven of warbling ignoramuses, don’t you see?”

“Her own wax figger”

Just like on earth — which, in heaven, for some reason, is known as Wart — everyone has to work. The difference, Sam explains, is that you get to choose your job.

Which, the Captain, says is reasonable: “Plenty of work, and the kind you hanker after; no more pain, no more suffering—” But Sam, again, sets him straight:

“Oh, hold on; there’s plenty of pain here — but it don’t kill. There’s plenty of suffering here, but it don’t last. You see, happiness ain’t a thing in itself — it’s only a contrast with something that ain’t pleasant….Well there’s plenty of pain and suffering in heaven — consequently there’s plenty of contrasts, and just no end of happiness.”

Says I, “It’s the sensiblest heaven I’ve heard of yet, Sam, though it’s about as different from the one I was brought up on as a live princess is different from her own wax figger.”

Continued to tinker with it

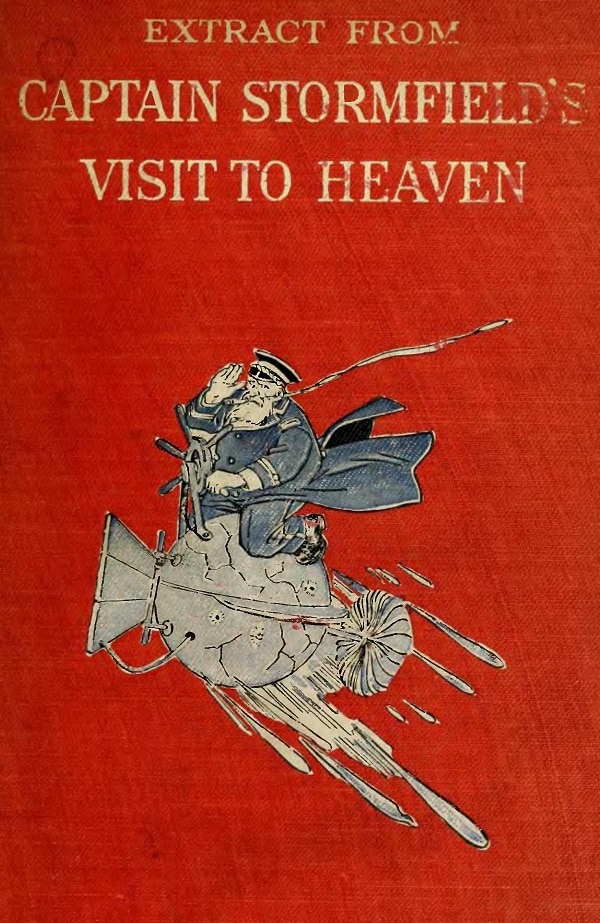

All of this is explained in Extract from Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven, the last book that Mark Twain published in his lifetime.

It’s a short book, just 121 pages in a small volume, reproduced in full in the 1996 edition from the Oxford Mark Twain series and accompanied by three commentaries.

In his afterword, James A. Miller writes that the story appeared in two installments in the December, 1907, and January, 1908, issues of Harper’s Monthly, and was then published as a Christmas book in October, 1909, six months before Twain’s death.

But its genesis had been decades earlier, first, as an idea in 1868 and, then, as a relatively finished manuscript in 1881. Twain continued to tinker with it every now and then over the next quarter century.

It’s easy to see why he kept going back to it. As published, Extract gives the sense of an unfinished sculpture. It has wonderful wit and social commentary but not much heft. Perhaps it was the structure of the thing, the Captain Stormfield story, that was the problem, not enough substance and bite. Or maybe Twain had nothing else to say.

It’s worth noting that the opening eleven and a half pages, about one tenth of the full book, deal with the Captain’s race against a comet which is fairly peripheral to the heaven story.

“For show, not for use”

Still, there is much that is delightful in Extract.

Such as the lowdown that the Captain gets from “an old bald-headed angel by the name of Sandy McWilliams…from somewhere in New Jersey.”

The Captain has been having a heck of a time getting the hang of his wings, and, finally, he realizes that Sandy and many others don’t wear wings. “I’ve been making an ass of myself — is that it?” To which Sandy replies:

“That is about the size of it. But it is no harm. We all do that at first….You see, on earth we jump to such foolish conclusions as to things up here. In the pictures we always saw the angels with wings on — and that was all right; but we jumped to the conclusion that that was their way of getting around — and that was all wrong.

“The wings ain’t anything but a uniform, that’s all. When they are in the field — so to speak, — they always wear them; you never see an angel going with a message anywhere without his wings, any more than you would see a military officer presiding at a court-martial without his uniform…

“But they ain’t to fly with! The wings are for show, not for use.”

When it comes to getting somewhere when they’re not on duty, angels do what everyone in heaven does, they just wish to be somewhere else — and there they are.

“A good deal surprised”

The Captain finds out from Sandy that white people of European stock are relatively few and far between in the United States section of the Earth (Wart) section of heaven. That’s because, for many centuries before Columbus landed on the New World, Native Americans were going to heaven.

In fact, Sandy says that “the main charm of heaven” is that “there’s all kinds here — which wouldn’t be the case if you let the preachers tell it….When the Deity builds a heaven, it is built right, and on a liberal plan.”

All sorts of people, and not just Christians, are in heaven, he explains. And people in heaven get their due, even if they didn’t get it on earth. For instance, Shakespeare is seen as a prophet, and Homer, too.

But they can’t hold a candle to Edward J. Billings, a common tailor from Tennessee.

“That tailor Billings, from Tennessee, wrote poetry that Homer and Shakespeare couldn’t begin to come up with; but nobody would print it, nobody read it but his neighbors, an ignorant lot, and they laughed at it.”

Those neighbors endlessly ridiculed Billings, even riding him around the village on a rail.

“Well, he died before morning. He wasn’t ever expecting to go to heaven, much less that there was going to be any fuss made over him, so I reckon he was a good deal surprised…”

Patrick T. Reardon

1.31.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.