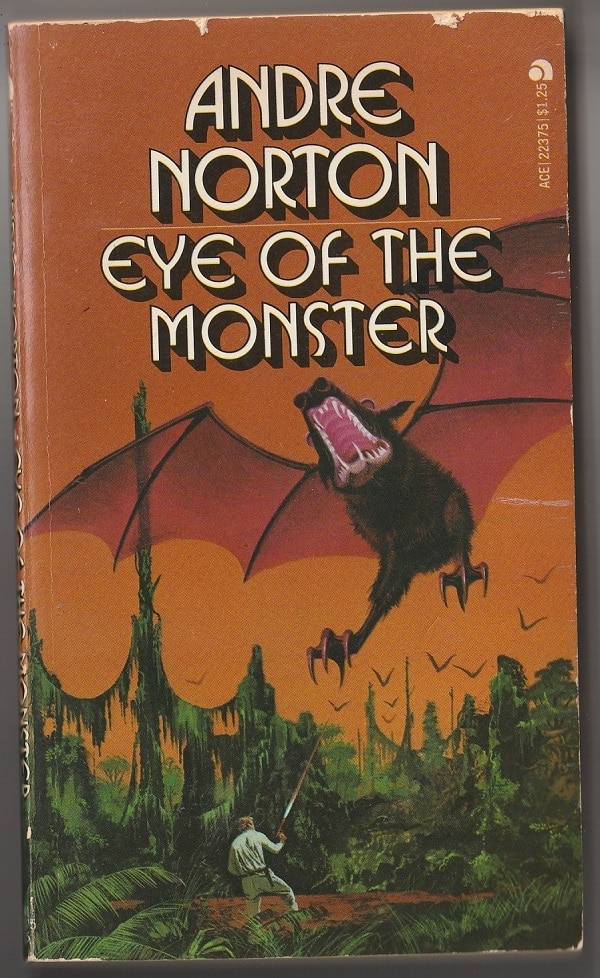

Andre Norton’s short 1962 novel Eye of the Monster is a disturbing story in which the native race of a world called Ishkur, pejoratively nicknamed Crocs, are brutal, foul-smelling and bestial.

For twenty years, the Crocs have been held at bay by the Empire’s Patrol — a space army of sorts — while humans have exerted colonial rule over the planet. Some have mined the world for its natural riches. Others, who have treated the Crocs with kindness, have studied them and developed what they believe is a rapport with them.

But, now, the Patrol is pulling out, and, as soon as they’re gone, the Crocs erupt into violence, massacring any humans — including their former “friends” — and any Salariki they are able to find.

Oversimplification

What’s disturbing about Norton’s novel is its parallels to white fears in colonial Africa as Blacks began gaining control of their nations during the mid-20th century. The history of Africa is filled with massacres, but no side was innocent. There were white massacres of Blacks, Black massacres of whites, and Black massacres of Blacks.

The problem with Eye of the Monster is how Norton oversimplifies the situation into Good and Bad, Right and Wrong.

On the Good side is Rees Naper, a young man who believes that “our ways were better than the rule the natives had for themselves before we came.” He argues that colonialism is good for the colonizers and for the natives.

On the Bad side are his Uncle Milo — a scientist studying the Crocs who believes that pulling the Patrol out “is the first step in righting the wrongs of colonialism” — and, of course, all the Crocs who, at their first chance, have rebelled.

They’ve killed Uncle Milo and the parents of Rees’s young friend Gordy and the relatives of two Salariki females, one an adult named Isiga and the other a child named Zannah.

Two types of non-humans

The Salariki are feline-like aliens who have much in common with the humans. For Norton, they are the equivalent of humans. In fact, she hints at a future romance between Isiga and Rees if the small group of survivors can get away from the Crocs.

By contrast, the reptilian Crocs are just plain beastly:

The Terran studied the peaceful scene, trying to guess at the source of that [Croc] stench. It could be that one of those horny bodies crouched very close to himn ow. Or the smell could be only a lingering reminder of the recent visit of an Ishkurian aroused to the fever pitch of some strong emotion.

All science-fiction is, to one extent or another, a commentary on the writer’s and reader’s present-day world.

Through Eye of the Monster, Norton seems to be finding great fault with the anti-colonial movement in Africa and the rest of the world at the time she was writing.

Disheartening

That’s disheartening to consider because, ten years earlier, in her first science-fiction novel Star Man’s Son, later published in paperback as Daybreak: 2250 A.D., Norton exhibited an open-mindedness toward race. In that book, her hero Fors forms a brotherhood with a dark-skinned stranger named Arskane.

It’s not just that Norton portrays one sort of non-human as attractive and another as repulsive. It’s her willingness to give no consideration to the reasons behind the actions the Crocs take once the space soldiers leave.

She seems willing to believe that these non-humans are so inferior, so un-human-like, that their violence is simply evidence of an intrinsic evil.

The oppression that went before

Looking across the arc of human history, it’s easy enough to find evidence of slaves or other captive people who, when they got the chance to rebel, inflicted violence on their former oppressors. But that violence had its roots in the oppression that had gone before.

It’s not that the killing of other people in a massacre is condoned. But it’s important to understand that such actions have their wellspring in much that has been previously inflicted.

For Norton, though, there is no thought given to how the Crocs might have been oppressed, enslaved, bullied by the human colonists. Instead, she demonizes them.

As a long-time fan of Andre Norton, I was dismayed to read this wrong-headed novel.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.25.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.