Rarely in literature does there appear someone as vitally alive as Fargo Burns, a character whose chaotically self-destructive actions and courting of danger and fragmenting psyche co-exist with — and, in a strange, odd way, complement — a desperate, yearnful groping for stability and sanity.

His strides frenetically up and down the sidewalks of New York City in 1971 like some demented child of Saul Bellow’s ever-energetic Augie March. He carries in his heart the mournfulness and bruised sensitivity of a James Agee child.

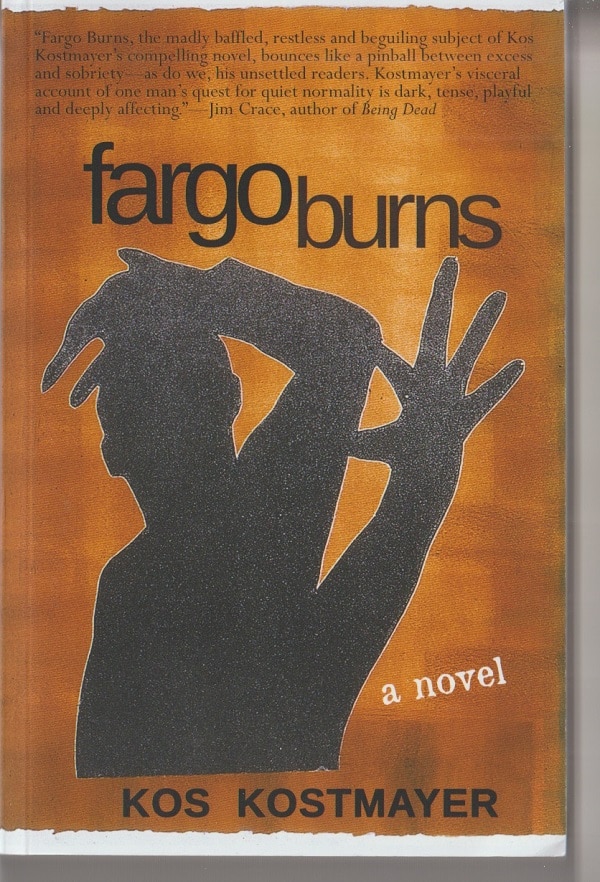

Kos Kostmayer’s novel Fargo Burns (Dr. Cicero Books, $15, 214 pages) opens:

Howling and half-naked in his torn and bloody clothing Forgo is a desperate man and dangerous to himself and others. He ricochets around his kitchen, heaving furniture into the street. The street is twelve stories down and Fargo fills the New York air with chairs and tables, lamps and dishes, frying pans and double boilers, brooms and mops and metal buckets, canned goods and Pyrex platters, a garbage can, a cookie jar, a toaster over, even the refrigerator door which he rips off and throws out the window.

The crowd below along 102nd Street sees a package of Velveeta cheese tumble down, and a wag yells up, “Hey, pal, don’t forget the fucking bread!” Out comes the breadbox.

Fargo’s three children hide in the apartment, not because they fear him — he is nothing if not a gentle father — but they can’t watch his disintegration. Their mother, his wife, Holly, has fallen in love with another man, and this seems to be the fuel for Fargo’s determined destruction of inanimate objects, filling the apartment floor with glass and mirror shards.

Holly opened the back door and found her husband crawling on the glistening floor like some creature in a fairy tale who has been placed under a terrible spell and turned into a farmyard beast.

Fargo was covered with blood, slippery as a butchered pig. Holly held him close, trying to calm him down. He thrashed and struggled in her arms until they fell to the floor on a bed of broken glass. They clung to each other desperately, like the last remaining sailors on a sinking ship, and wept.

“Miracle and monstrosity”

When Fargo is taken away in a straitjacket, he seems to have nowhere to go but down.

Yet, while drying out in the jail hospital from his multiple abuses of controlled substances, he begins to meet with a psychiatrist, Lane Dubinsky, who is tall and slim and looks more than a bit like Virginia Woolf. And, after he’s set free, he keeps going to her office every week to face himself and his past and his present, and maybe his future.

Leaving one early meeting, he studies a line of huge nightmarish canvasses lining her office wall and asks if they were by one of her patients.

Lane laughed and said:

No, I did them.

You?

You seem surprised.

Well, they look like they were done by — I don’t know — Like they were done by—

By what? said Lane.

Well, by some maniac, admitted Fargo. I thought I was supposed to be the maniac, not you.

By way of explanation, Lane mentions that Montaigne said he knew of “no more evident miracle and monstrosity” in the world than himself.

Yes, but I’m the patient, you’re the therapist, said Fargo. Don’t you need to be sane?

I need to be able to help you.

You think you can?

I hope so, said Lane.

“Sex and death”

In fact, the weekly sessions do seem to help Fargo — not so much to give up drugs or give up drinking or give up furtive sex with Billie Speed, the girlfriend of Kohler Skane, a stone-cold murderer — but to begin, at least, to consider the possibility of a life less tumultuous.

To begin to think of getting a job and, with Lane, to work through the pain of his childhood. And even to hope to develop a healthy romantic relationship with an old friend, Sarah Mandy O’Brian.

But Billie is a Calypso to Fargo’s wanderings through the crooked byways of his psyche and New York City, and he is happily enslaved by her vibrant, edge-of-insanity personality and dynamic sex.

Fargo knew he was drawn to Billie, in part at least, because she combined two primary, but usually mutually exclusive, biological ingredients, namely sex and death, into a very tasty cocktail. Being in bed with Billie was like attending your own funeral without having to die first.

It was morbid as well as delicious, compelling as well as frightening. Fargo would sneak into her apartment whenever Kohler Skane was away (Kohler made regular trips to Philadelphia…receiving and selling stolen goods, buying and selling drugs, committing an occasional robbery and every once in a while cutting someone to ribbons, either for profit or fun) and something about having sex with Kohler’s girlfriend in Kohler’s own apartment, Kohler’s own bed, made Fargo feel like an undercover cop, which is to say someone whose identity could only be affirmed in the presence of his enemies.

In addition to the danger, it was a lot of fun. After one lovemaking session, as the “sweet aroma of their sex filled the room,” Fargo happily says:

“If somebody threw a handful of seeds into this room, they would blossom in mid-air. We would be surrounded by wildflowers.”

“Willful and Germanic”

For his therapist, Fargo is a client whose saving grace is his sense of humor “which, for all its morbidity, at least possesses the virtue of buoyancy.” He strikes her as being “wary as a wild fox and looking very much like a man who is nothing if not desperate to be sane.”

His life is unfocused, Lane thinks, and lacking in common sense and discipline. Nonetheless, he is filled with spirit.

He isn’t a happy man, but he is a lively one, and she would guess that underneath his anger and self-pity lies a great capacity for joy.

Fargo is a man who loves and enjoys children, particularly his own — a good sign. Nonetheless, she thinks:

There is, however, something willful and Germanic in his soul, a kind of foul and viscous liquid at the center of his being (the psychic equivalent of a swamp) which troubles her almost as much as it torments him.

She regards this emotional swampland as the breeding ground of his pain and would love to help him drain it, but at the same time she is aware of the fact that his pain his very precious to him: he seems almost proud of it, in fact, the way certain cancer patients will take pride in the size of their tumors.

Like a heartbeat

Novels with self-destructive heroes usually aren’t much fun to read. But Fargo is no downer.

He is snappy. And he is jerky. And he is almost always in some kind of psychic pain. But he also has a deep well of joie de vivre.

Fargo’s an entertaining companion to the reader as he bops across the face of New York like a heartbeat.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.27.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.