Somehow, somewhere, I obtained a fairly solid copy of P.G. Konody’s small book Filippo Lippi, published in London in 1911 as part of a series titled Masterpieces in Colour.

As best I can remember, I found it in one of those free book boxes that are scattered around many Chicago neighborhoods. This was at least a year and a half ago, before last November when my wife and I spent eleven days in Florence where I saw a great many paintings by Lippi and by his similarly talented son Filippino.

So, reading the book was, for me, a return to those Florence days of swimming in a sea of Renaissance art, finding at seemingly every turn astonishing art in museum after museum and even random churches, little nothings on this or that small street.

The physical act of reading this book that is more than a century old gave me great pleasure. Its eight color illustrations on shiny pages were state of the art for 1911 and have weathered eleven decades well. The paper with Konody’s text is thick and sturdy and well laid-out.

A personalized deckling

Its 80 pages have deckled edges — that is, irregular edges — but not the sort of deckling that is done by the printer. Rather, the deckling was done by the book’s first owner because, like many fine volumes published in that era, it arrived with the pages unopened.

In the traditional printing process, large pieces of paper were printed with several pages of a book and folded into the binding. This left the outside edge of every four pages closed. Usually, the printer would slice off the edges of these pages, but, in some cases, they were left uncut — unopened — so the purchaser could have the pleasure of cutting them open to find the words inside, like a small treasure.

This cutting was easy enough to do with a small knife, but, sometimes, the cutter got a bit sloppy. That’s what happened near the end of Filippo Lippi, with a largish triangle of the upper corners of the last four pages gone because of an inattentive cutting of the pages open. This clumsiness didn’t affect any of the text and, in fact, added a zestful sort of personalization to the book.

I knew, as I read it, that someone else had read the book earlier.

Filippo Lippi “Madonna with the Child and Two Angels”

Father and son

In preparation for our trip last fall, I read The Uffizi, a 1980 book about the famous Florence museum by Margherita Lenzini and Emma Micheletti which I also found, somewhat battered, in one of those free little libraries.

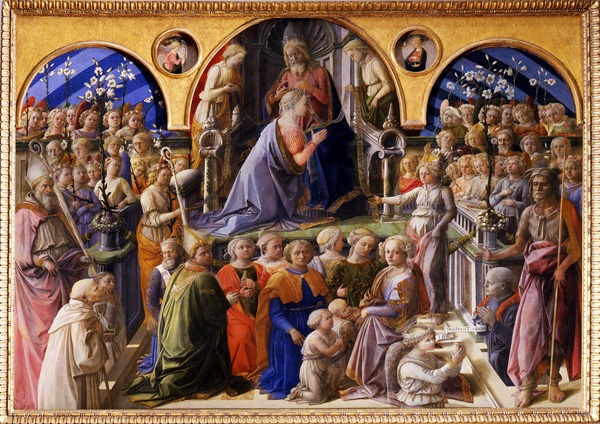

I was captivated by the cover, featuring a detail from what I learned is The Coronation of the Virgin by Filippo Lippi, and it was one of the artworks I made a beeline to when I got to the Uffizi.

Filippo Lippi “The Coronation of the Virgin”

While in a Florence bookstore, I came across a beautifully produced 2022 monograph on Lippi’s son — Filippino Lippi: An Abundance of Invention by Jonathan K. Nelson — which I read when we got back to Chicago. Another book I read back home was Gloria Fossi’s 1989 Filippo Lippi which, on its cover, has a beautiful detail of a dancing Salome from Lippi’s Stories from the Life of John the Baptist.

Truth be told, I’m afraid that I’d gotten the two Lippis combined in my head as a single artist. The books by Fossi and Nelson quickly made me aware of my error.

It also made me aware not just that I wasn’t differentiating between father and son but also that I had missed a lot of their work that was there in Florence if only I’d known to look for it.

Ah, well. I’ll just have to go back.

Scandal and devoutness

In the meantime, I had been holding onto Konody’s small book on the elder Lippi, and recently, well — if you’re a reader, you know what I mean — the time was just right.

Paul George Konody, who was born in Hungary and lived most of his life in London, was a noted expert on the art of the Renaissance. In 1903, he wrote a book on Filippino Lippi, following it eight years later with this book on the elder Lippi.

Filippo Lippi was a Carmelite monk who didn’t let his vows of chastity get in the way of a life of sensuality. Indeed, he lived a scandalous life, well-documented, highlighted by his kidnapping of a nun named Lucrezia Buti in 1456.

At the time, Lippi was 50 and Lucrezia was 21, Konody notes, and it seems she was more than willing to be “kidnapped.” Their son Filippino was born a year later. Konody writes:

There can be no doubt that the gay friar led the life of a true “Bohemian” — that he was fond of women and wine, and wasted his substance in the company of his boon companions.

Nonetheless, Konody cautions his readers not to read into Lippi’s many paintings of religious subjects, particularly the Virgin Mary, a lack of reverence and devoutness. Yes, Mary often has the face of Lucrezia, but, even so, she is an expression of the painter’s deep religious feeling.

Filippo Lippi “Madonna with the Child and Scenes from the Life of St. Anne”

He notes that the widely respected American art critic Bernard Berenson, who found fault with Lippi in some ways, still acknowledged that the artist’s “place is with the genre painters, only his genre was that of the soul.”

“Before painting, he looked at them”

For Konody, Filippo Lippi was a trail-blazer, “one of the greatest initiators of the Renaissance in painting,” adding:

He is the first Florentine who shows a real appreciation of the beauty of Nature, who allows real daylight to enter into his pictures, and who studies reflections….

Again and again Fra Filippo acts as initiator and sets the fashion for whole generations of artists. He is one of the first to experiment with devices for producing illusions of depth…Every phase of the triumphant progress of Renaissance art finds an echo in Filippo Lippi’s painting.

Filippo Lippi “Nativity”

Lippi, writes Konody, borrowed techniques and approaches from his great contemporaries and also “applied the same keen intelligence to the study of the living world around him.” And, perhaps the greatest compliment, Lippi painted humans who looked like humans — men, women and children.

He was one of the first painters of his school who makes us feel that almost every character in his pictures is the result of personal observation — is practically a portrait…..

As M. Andre Maurel has it: “Before painting faces, he looked at them, which was a new thing…He was a great painter, because he was a man.”

Filippo Lippi “Annunciation”

Patrick T. Reardon

9.12.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.