Why do I read a book? I mean, this particular book or that one. I mean, what triggers the decision to open a book and start reading.

Obviously, there are books we have to read — for a book review, say, or for research or for school or in the course of doing a job. But, when the reading of a book is entirely in our own hands, what impels us to start?

Or, earlier, what impels us to pick up a book and examine it with the idea of someday reading it? Perhaps the book is about a subject in which we have an interest. Or it’s written by an author we like. Or there’s something about the cover that makes us want to know what’s inside.

That happened to me a couple weeks ago at one of the many free book library boxes in my Chicago neighborhood.

There, on the ground in front of the book box pedestal, was a large cardboard carton of books, some of which had been damaged by a recent light rain. One that had escaped the rain looked, nonetheless, somewhat bedraggled because it was in a shabby plastic slip-on cover.

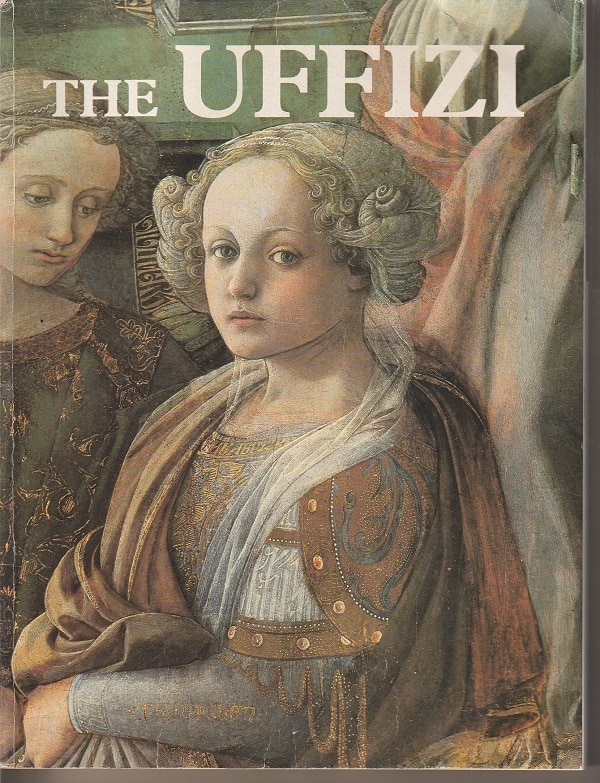

Roughly 11 inches tall and eight inches wide, the book was titled simply The Uffizi with no other words on the cover, and, when I looked inside, it turned out to be a guide to the Florence museum, published in 1980 in Italy and featuring 145 photos in color. The title page indicated that its Italian authors were Margherita Lenzini and Emma Micheletti. In small type by the copyright information was a notice that the English translation was by Merry Orling.

For a 40-year-old guidebook, The Uffizi seemed in relatively good shape. The printing wasn’t as sharp and clear as one would expect from a new book today, but the colors hadn’t faded much, if at all. My wife and I are planning to spend more than a week in Florence later this year, and I’m figuring to spend a lot of that time in the Uffizi. So, the guidebook might help me to prepare.

But that isn’t why I picked it up and took it home.

I did that because of Theopista.

The face

Of course, I didn’t know her name was Theopista when I saw her face on the cover.

All I knew was that the image arrested me.

It stopped me in my tracks. It captured me. It grabbed me and wouldn’t let me go.

This thoughtful, self-contained, deep-feeling young woman stared out from the cover, not so much looking at me but looking at some distant imaginary point beyond my right shoulder, pondering, enduring.

There was no indication that I could locate inside the book about this cover image or about who had painted it, but I figured I’d find this face somewhere in the book as I paged through. That didn’t happen.

The book, for all its batteredness and age, is filled with spectacular masterpieces that are held in the Uffizi —Titian’s Venus and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, Michelangelo’s Holy Family, Raphael’s Virgin of the Goldfinch, and Leonardo da Vinci’s Annunciation as well as works by Tintoretto, Canaletto, El Greco, Fra Angelico, Giotto and Rubens and self-portraits by Rembrandt, Delacroix, David and Velasquez.

But nowhere in its 95 pages of artistic treasures could I find the face on the cover, not as a portrait, not even as a detail in a larger painting.

The Coronation of the Virgin

The woman’s face on the cover reminded me of some of the women of Botticelli but without the long neck that he gave them. Think of Venus in The Birth of Venus.

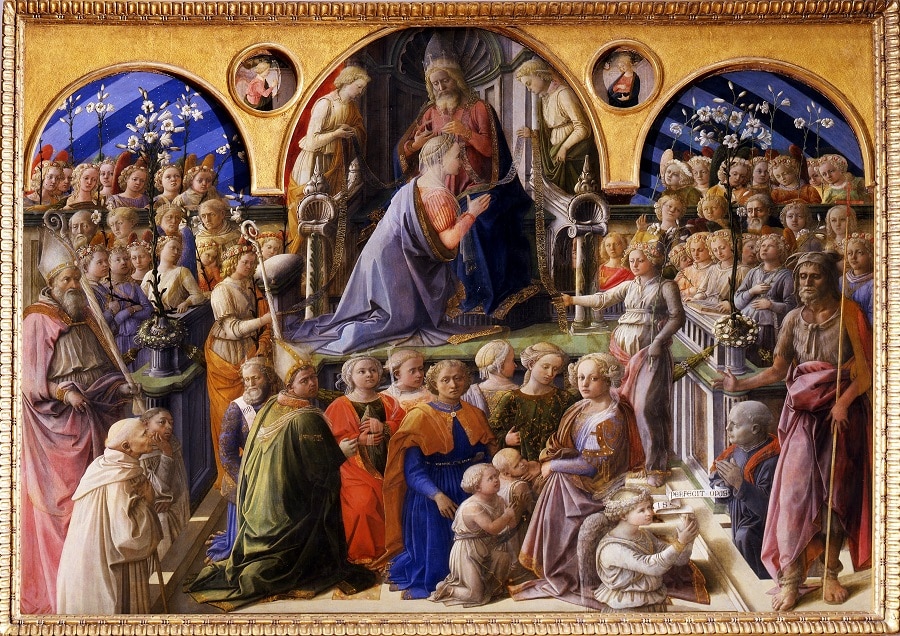

I might have looked for a long time through books in search of the woman, but, in this age of the internet, I was able fairly easily to conduct a search using the image and, in only a little bit, found the source — The Coronation of the Virgin by Filippo Lippi.

There she was, the face from the cover, seated in the lower right quadrant of the painting, originally displayed above the high altar of the church of Sant’Ambrogio (St. Ambrose) in Florence and now at the Uffizi.

Searching here and there for information, I found that the painting was financed by a death bequest from Francesco Maringhi, an official at the church, who is pictured kneeling a bit further to the right of the woman from the cover.

Lippi was born about four decades before Botticelli and died when the younger artist was in his early twenties. The face of the woman on the cover makes me think that Botticelli may have learned a thing or two about painting faces from his predecessor, but I have no information to that effect.

The painting is done in three vertical sections.

The ones on the right and the left are filled with crowds of saints, angels and Biblical figures. At the top of the center section is a kneeling Mary being crowned by God the Father or maybe an older-looking Jesus.

In the bottom of the center section are more saints as well as a family grouping that I found out represented Saint Eustace in a blue robe, his wife Theopista and their sons Theopisto and Agapius.

Four martyrs

Eustace was a Roman general who converted to Christianity. As a result, he lost his wealth, was separated from his family and went into exile. Later, when he was called back by the emperor Trajan to lead the Roman army, he was reunited with Theopista and the boys. However, Hadrian who took over as emperor after Trajan’s death ordered the family members to sacrifice to pagan gods. When they refused, they were martyred in 118 AD.

Almost universally, accounts of the painting as well as stories of the family and their martyrdom identify Eustace as a saint and mention Theopista and the sons in passing. Which seems to me to be odd since, well, they all were martyred so they all should be considered saints, right?

At least one Christian institution agrees.

On September 20 each year, the Antiochian Orthodox Christian archdiocese of North America commemorates St. Theopiste (Theopista) with her children, as a long webpage explains. The archdiocese also celebrates that as the feast day of her husband, identified as Great Martyr Eustathius (Eustace).

“Give me six months”

Lippi’s richly beautiful image of Theopista gains added luster from the story of her martyrdom with her husband and sons as new steadfast Christians.

I don’t know if the story of Theopista was in Filippo Lippi’s mind when he painted her. For me, that background gives added meaning to her thoughtful gaze and soft vulnerability.

And I don’t know if Robert Browning gave much thought to her face when, in the mid-nineteenth century, he wrote “Fra Lippo Lippi,” a dramatic monologue in the voice of the artist whom the poet thinks of as something of a scamp.

It opens with the monk-painter being caught in the brothel district of Florence, and it’s clear from the poem, available online at the Poetry Foundation, that Browning knew of Lippi’s Coronation of the Virgin.

Near the end, Browning has Lippi acknowledge his weakness despite being a man of the cloth:

Oh, the church knows! don’t misreport me, now!

It’s natural a poor monk out of bounds

Should have his apt word to excuse himself:

And hearken how I plot to make amends.

I have bethought me: I shall paint a piece

… There’s for you! Give me six months, then go, see

Something in Sant’ Ambrogio’s! Bless the nuns!

They want a cast o’ my office. I shall paint

God in the midst, Madonna and her babe,

Ringed by a bowery, flowery angel-brood,

Lilies and vestments and white faces, sweet

As puff on puff of grated orris-root

When ladies crowd to Church at midsummer.

And then i’ the front, of course a saint or two—

Saint John’ because he saves the Florentines,

Saint Ambrose, who puts down in black and white

The convent’s friends and gives them a long day,

And Job, I must have him there past mistake….

He may be a man who hangs around brothels, but he is also a man who, in six month’s time, can give you God and the Madonna and saints and, even, the long-suffering Job from the Old Testament.

And Theopista.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.1.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.