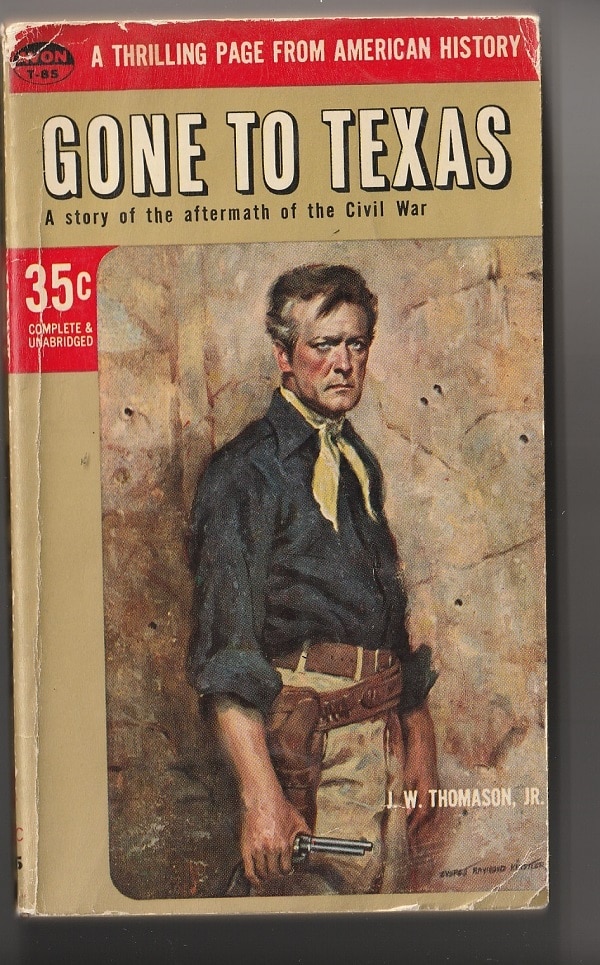

The softcover edition of John W. Thomason Jr.’s Gone to Texas is visually striking but, in the manner of many paperbacks, misleading.

Nevertheless, it turned out to be misleading in a good way since it got me into Thomason’s western and, even more, into his own remarkable art of the West, much different from the cover art.

I found the book in one of the giveaway book boxes that dot my Chicago neighborhood, and I was arrested by its cover image — a painting by Everett Raymond Kinstler that shows a tired, perhaps angry, middle-age soldier staring out at the viewer and holding a pistol at rest in his right hand. With his blue shirt and yellow bandana, he looks like an actor in a John Wayne movie, actually a lot like Robert Ryan.

The paperback was published by Avon in 1950 when Kinstler was in his mid-20s and doing a lot of covers and inside work for Avon as well as for comic book publishers such as Dell.

The Gone to Texas cover, though, has the gravity and distinctness of a dramatic portrait. It’s the antithesis of most pulp covers. And it hints at Kinstler’s later highly successful career as a portrait painter of such luminaries as Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, Katharine Hepburn, Leonard Bernstein and — fittingly, in light of the Thomason cover — John Wayne.

Kinstler’s cover gave the Thomason novel an unusual old-timey feel, far from the action-oriented images on most paperback westerns.

Inside, Gone to Texas was different from most other westerns but not in the way that image of a tired, oldish soldier suggests.

A callow veteran

Inside, Thomason tells the story of 24-year-old Lt. Edward Cantrell, a Civil War veteran who, after three postwar years of aimlessness, has rejoined the Army and has been assigned to duty in Texas.

Unlike the subject of Kinstler’s cover painting, Cantrell is still more than a bit callow despite his war service. Indeed, hardly a man of the world, he’s bowled over by several interactions with a lovely, fire-cat of a Southern belle named Brandon Hawkes.

While the novel has its appeal as a kind of love story to the wide-open spaces of Texas, the scores of drawings that Thomason sprinkles through the text are its most attractive feature.

In the paperback I found, there are only about 40 illustrations. However, I tracked down a copy of the original hardcover edition from 1937 and was pleased to find a hundred or so.

A more relaxed cover

Thomason, a Texas native, enlisted in the U.S. Marines in 1917 and served through World War I, the interwar period and World War II, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel, until his death in 1944 at the age of 51. During that time, he published several collections of military short stories, some historical non-fiction and two novels.

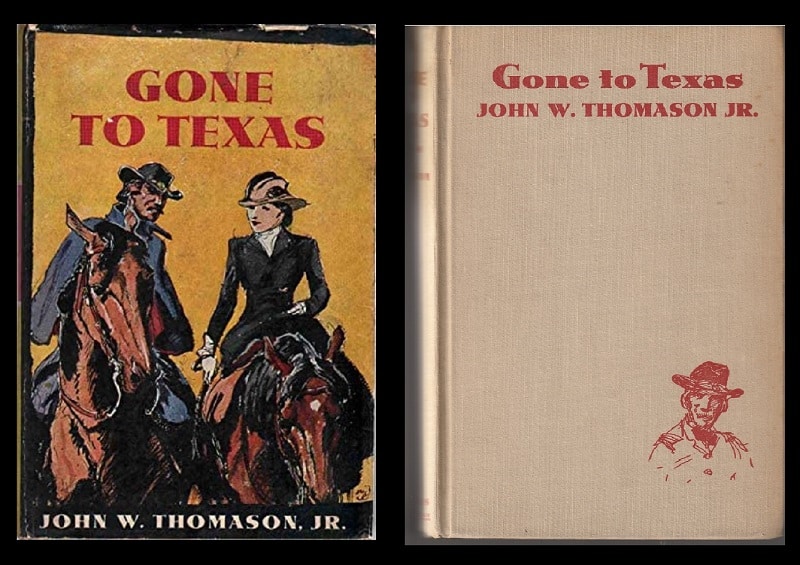

Gone to Texas came out in 1937, and the copy I obtained was in great, if dusty, shape, except for the dustjacket which arrived in pieces. Nonetheless, via the Internet, here’s Thomason’s cover image for the hardback, as well as the novel without its jacket.

While Kinstler’s cover has an austere beauty, Thomason’s more relaxed image gives a better sense of the novel itself and the other images inside.

Women

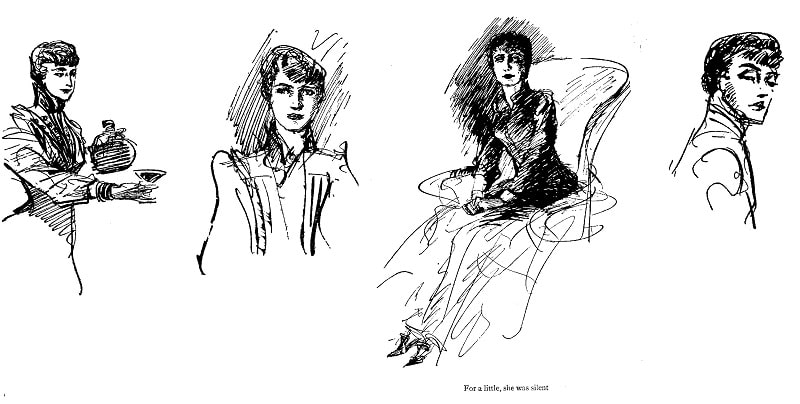

For instance, Thomason, for all his military background, seems to have enjoyed drawing images of women, such as these five:

And the interesting thing is that none of these women is an important character in the story. He just liked to draw them, it appears.

One woman who was important to a subplot in the story was Vashti Silver, a rich, beautiful, clever woman who, single-handedly, had built a financial empire in Texas and was dabbling in some clandestine illegal activities, such as gunrunning.

Brandon

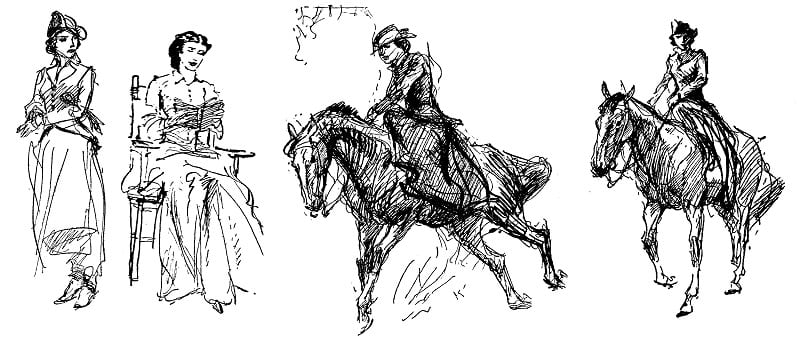

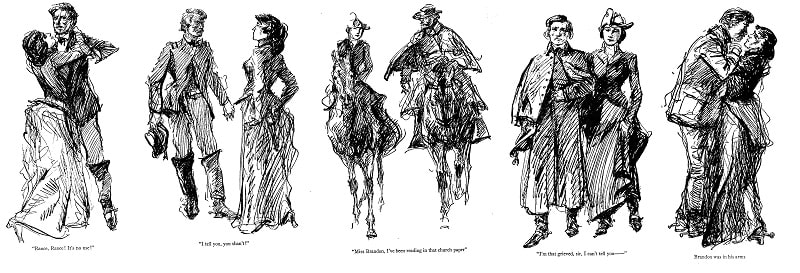

Of much greater importance to Thomason’s book, though, is Brandon, that fiery former rebel who causes Cantrell a great deal of emotional discomfort — and physical pain. Thomason offers several images of Brandon on her own:

And more images of Brandon and Cantrell together, ending at far right with a kiss.

A romance

I would imagine that anyone who starts reading Gone to Texas knows right from the start where things are going, and the ending is suitably happy with Brandon and Cantrell riding off into the sunset.

Their romance is in the foreground of the novel, but, as I mentioned above, I came away from Thomason’s book with the sense that, in a deeper way, the novel was his love letter to the spirit and beauty that humans found in the natural world in Texas.

Here’s one illustrative paragraph:

The day advanced and the climate changed with the bewildering suddenness that, he was to learn, characterized Texas — yesterday they rode in winter; this morning it was spring. The sun warmed them, and their wet coats steamed visibly, and the youngest trooper — a pink-cheeked boy named Smedes — raised a song. The lagoon ended, and in an hour’s riding they came to a winding yellow creek, banks full from the rain, and then to a wagon track and a gravel-bottomed ford.

See what I mean?

Patrick T. Reardon

1.31.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.