The appearance of Mary, the mother of Jesus, to Aztec peasant Juan Diego in December, 1531, on the hill of Tepeyac outside of Mexico City, is different from and more important than any of her other reported apparitions over the centuries.

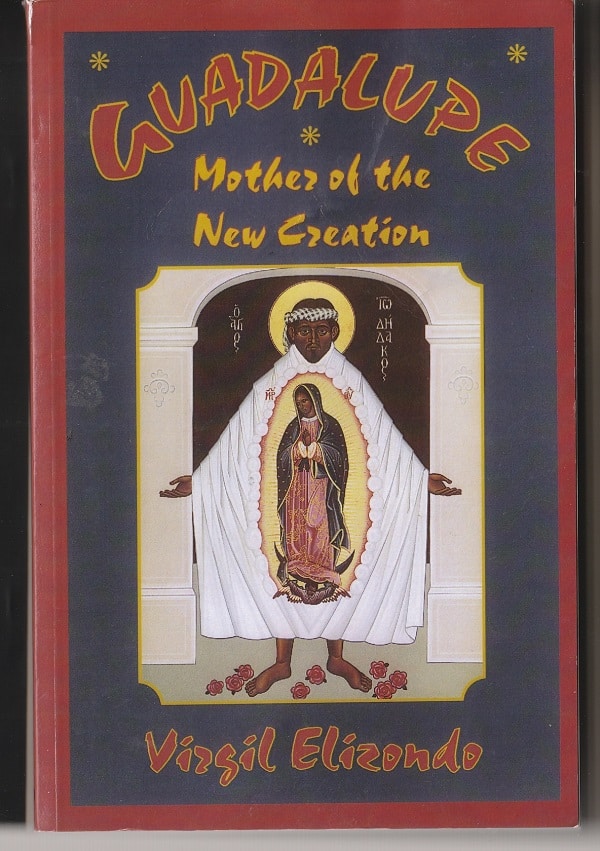

That’s one of Virgil Elizondo’s assertions in Guadalupe: Mother of the New Creation. He writes:

Its full impact can be appreciated only in the context of salvation history itself. For Guadalupe is not just a Mexican happening — it is a major moment in God’s saving plan for humanity.

The Blessed Mother’s appearance to Juan Diego at Tepeyac — Elizondo says a better word is her “encounter” with the young man — took place just 39 years after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World, as Europeans came to call it. It was, of course, an old world for the indigenous people who had lived on the North and South American continents for millenniums.

Early on in his short 1997 book, Elizondo, a leading scholar in Catholicism’s liberation theology and Hispanic spirituality, states:

The more I try to comprehend the intrinsic force and energy of the apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe…, the more I dare to say that I do not know of any other event since Pentecost that has had such a revolutionary, profound, lasting, far-reaching, healing, and liberating impact on Christianity.

Then, in the final pages of the book, Elizondo, a community activist-priest known as “the father of U.S. Latino religious thought,” writes:

She is always present in the Tepeyacs of the world — the barrios, the slums, the public housing projects, the ghettos, and other such places. She will never leave us because she has been intimately woven into the cloth of our suffering-resurrecting existence. While others crucify us, she resurrects us.

Guadalupe is the most prodigious event since the coming of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

How historic?

Those are strong statements, especially for an event that, Elizondo acknowledges in passing, isn’t considered “historic” in the way Western historians define the term.

The story is well-known to believers and non-believers:

Mary appears to Juan Diego and sends him to Archbishop Juan de Zumárraga to build a church on the hill of Tepeyac in her honor. The archbishop demands a sign. The Virgin loads the Indian’s mantle with flowers, and, when the mantle is lowered, not only do the out-of-season flowers fall to the floor before the church leader but the mantle itself is found to be decorated with a striking and seemingly miraculous painting of Mary, a work that is now known as Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The problem, from the point of view of modern historians, is that no contemporary documents, even from the archbishop, a prolific writer, have been found that refer to the appearances or the miracle.

The earliest may be the Codex Escalada, a single page of parchment of images and text in the Aztec language Nahuatl, mentioning the appearances as well as the death of Juan Diego in 1548. But its authenticity has been questioned.

More accepted is the 6,000-word Nican Mophua, also written in Nahuatl, that dates from 1556, a quarter of a century after the encounter at Tepeyac. This document is the heart and soul of Elizondo’s Guadalupe: Mother of the New Creation.

Elizondo — who made his own translation of the Spanish version of the Nahuatl original — calls it a poem.

Historic and spiritual

It’s worthwhile, I think, to remember that, for the same reasons, the Gospels and other New Testament writings aren’t considered “historic” either.

The first non-Biblical, non-Christian account of Jesus and such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, John the Baptist and James the Just didn’t come for more than half a century — not until around 93 or 94 AD when Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote his Antiquities of the Jews. (The book is also, for Jewish historians and scholars, an important outsider account of the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD.)

So, the Nican Mophua is like Josephus’s Antiquities inasmuch as it is a physical document that recounts what it asserts is an event that actually happened.

But it’s also like the New Testament books inasmuch as it is a description of a spiritual event that occurred in the past although not necessarily witnessed by the writer.

The earliest of the Gospels is Mark’s, dating from 66 AD to 70 AD, at least three decades after the life of Jesus. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians is the earliest New Testament book, written around 48 AD or more than a decade after the ministry of Jesus.

“The Owner of What is Near and Together”

As a poem — as a religious poem — the Nican Mophua reads like a Bible story.

For me, it brings to mind such Genesis episodes as Adam and Eve in the Garden or events from the life of David. And it has the same narrative quality as the scenes of Jesus with the woman at the well and with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, as well as such parables as the Good Samaritan.

The similarities have to do with how detailed the story is and also with how resonant those details are spiritually. There is a lesson being taught here.

For instance, in setting the scene, the writer notes that the Aztecs had surrendered ten years earlier to the Spanish forces with their Catholic missionaries:

Thus faith started: it gave its first buds; and it flowered in the knowledge of the One through Whom We Live, the true God, Teotl.

A few paragraphs later, when Mary encounters Juan Diego on the hill, she identifies herself as

“the Ever Virgin Holy Mary, Mother of the God of Great Truth, Teotl, of the One through Whom We Live, the Creator of Persons, the Owner of What is Near and Together, of the Lord of Heaven and Earth.”

Extraordinary titles

These titles are extraordinary in a Christian setting. For one thing, Teotl is the Aztec name for God.

For another, as Elizondo notes, Mary’s titles are the names at the heart of “the purest preconquest theology of the Nahuatls.” This, he writes, is “a most important revelation.” Through her statement, Mary “reestablishes the authenticity and veracity of these holy names.”

In addition, this encounter is taking place on the hill of Tepeyac which, in Aztec theology, was the sacred mountain of the goddess Tonantzin.

All of this signals, Elizondo writes, the the aim of Mary — and of God — is not to abolish the Aztec faith but to merge it with Christianity. This is the “New Creation” of the book’s title:

She does not destroy the natives’ gods nor deny the God of Christians but presents something much more attractive and humanizing — both to the Indians and the Christians of that moment of history and even today.

A new metaphysics

Elizondo writes that the strength of Aztec metaphysics was “its emphasis on the interconnectedness and interdependence of all creation,” while its weakness was its failure to recognize the dignity of the individual. Indeed, individuals were literally sacrificed on a bloody altar for the greater good of the community.

Similarly, Western metaphysics is strong in the “isolation and exaltation of the individual,” while its weakness has been the sacrifice of the community to the will and power of the strongest person.

Guadalupe merges the two into a new metaphysics that recognizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of all creation while equally recognizing the uniqueness and value of the individual within the cosmic.

For the Aztecs, history was cyclic and shaped by cosmic forces. For Christians, it was linear and shaped by individual actions.

For Guadalupe, history is continuity with the past recycled into the new being of the future that begins in the present moment; the past and the future are alive in us.

“A beautiful celestial song”

In Elizondo’s translation, the Nican Mophua is richly poetic. Consider, for instance, the “beautiful celestial song” that draw Juan Diego to his encounter with Mary:

He heard singing on the summit of the hill; as if different precious birds were singing and their songs would alternate, as if the hill was answering them. The song was most pleasing and very enjoyable, better than that of the coyoltotol or of the tzinizcan or of the other precious birds that sing.

Birds in Aztec thought were seen as mediators between heaven and earth. The coyoltotol was the symbol of fruitfulness.

When Mary calls to him — “Dignified Juan, dignified Juan Diego” — he finds her a beautiful woman, dressed in “clothing…like the sun,” giving off rays.

And the rock and the cliffs where she was standing, upon receiving the rays like arrows of light, appeared like precious emeralds, appeared like jewels; the earth glowed with the splendors of the rainbow.

The mesquites, the cacti, and the weeds that were all around appeared like feathers of the quetzal, and the stems looked like turquoise; the branches, the foliage, and even the thorns sparkled like gold.

“I will hear their laments”

More important, though, more astounding, than such physical wonders is how Mary acts. She talks with Juan Diego as an equal. She listens to him, even as she sends him to the archbishop.

And that was the purpose of the church she was asking the archbishop to build:

There I will hear their laments and remedy and cure all their miseries, misfortunes, and sorrows.

Mary is not interested in telling the people the chapter and verse about how to behave — not interested in the things that concerned the Inquisition, not interested in browbeating the common people. Not seeking to shame or judge guilt.

She wishes only to be of service. And this, Elizondo, writes, is the central core of the New Creation that she brought.

She wishes only to be of service — especially to those who are on the margins of society, those who are too poor to be noticed, those who are too dark to fit in, those who are considered ugly or dirty or smelly.

A mestizo spirituality

This is a mestizo spirituality, a mulatto spirituality. It is a New Creation of Christianity which is based on “openness to everyone without exception.” Elizondo writes:

At Tepeyac no one is to be rejected. Tepeyac becomes the most sacred space of the Americas precisely because of the unlimited diversity of the peoples who experience a common home there.

Precisely because everyone is welcomes there and experiences a sense of belonging, is listened to with compassion and senses the energy of true universal fellowship, the face of God is clearly seen while the heart of God is experienced intimately and tenderly.

Tepeyac, writes Elizondo, is “not a sacredness that scares, separates, and divides but the sacredness of the holiness of God that allures, brings together, and unites.”

All of this from the story of an encounter between a peasant and a beautiful woman, of a mantle full of flowers and an image of a dark-skinned mother of Jesus.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.2.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.