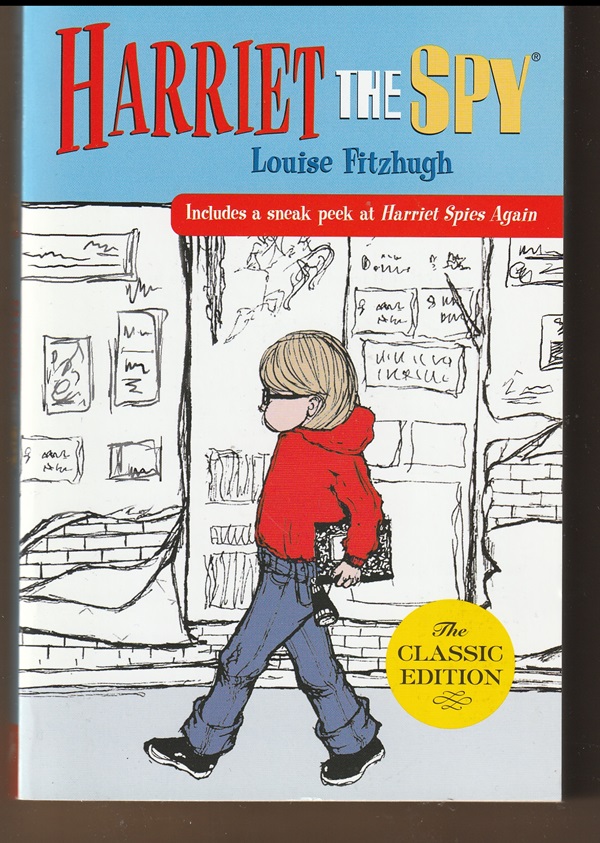

The plot of Louis Fitzhugh much-loved Harriet the Spy doesn’t yield a moral. But the life of Harriet does.

What I mean to say is that some schools and libraries have banned the 1964 novel because of claims that it sets a bad example and teaches children to lie and spy and talk back and act out.

But Harriet the Spy isn’t about spying although eleven-year-old Harriet M. Welsch does a lot of watching and listening to other people, unseen. She’s got a child’s curiosity, a human’s curiosity. Which of us has not eavesdropped on the conversation going on behind us in a restaurant or on an airplane?

Harriet is filled with life, filled with a lust for understanding life:

“I want to know everything, everything. Everything in the world, everything, everything. I will be a spy and know everything.”

And the novel isn’t about lying although, to protect her friends’ feelings, Harriet does lie at one point — to say that her accurate observations about them weren’t true (although they were). And she apologizes.

She is filled with a passion for knowing reality, which is to say, a passion for truth. She does not want to trick herself or be tricked. She is trying to figure out how to do this while also engaging deeply with all aspects of living.

And it isn’t about talking back or acting out, for the sake of talking back or acting out, although Harriet does throw tantrums when she is being squeezed into a non-Harriet contortion by her parents, her teachers, her friends.

Tiny force of nature

She is filled with a radical insistence to be herself, not to go along simply to go along, to fit in simply to fit in. She is a tiny force of nature, the one true vibrant human being in the lives of those around her.

And it isn’t about getting in trouble although Harriet finds herself in a lot of trouble at one point because the notebook in which she has written clear-eyed observations about life and Manhattan where she lives and the way people interact and her classmates and friends has fallen into the wrong hands (of her classmates and friends), and she has been made an outcast.

At the height of all this trouble, Harriet sits on the toilet and writes in her new notebook:

“I LOVE MYSELF.”

That is the moral of Harriet the Spy. It is not: To love yourself. It is: To be a person like Harriet who is so alive that she can say, “I LOVE MYSELF.”

It is about not just accepting yourself. It is about having no other thought in the world than accepting yourself. Indeed, it is about how accepting yourself never enters the picture. Harriet is so much herself that she never thinks to be someone else or to tone herself down or to put on some persona.

What does it feel like?

And what Harriet wants to know goes way beyond facts and data. When she says she wants “to know everything,” what she means in the deepest way is what does it feel like.

Her mother, who is caring and loving and nurturing in a parent’s kind of way, is asked by Harriet how she met Harriet’s father. It was on a boat crossing the ocean:

“I was coming out of the dining room and I bumped into him. It was a very stormy crossing and he threw up.”

But that’s not what Harriet’s interested in. What did it feel like? “To have someone throw up on your feet?” her mother says.

“NO,” said Harriet in an exasperated way, “I mean, what does it feel like when you meet the person you’re going to marry?”

“Doesn’t make sense”

A few pages later, when she finds out that Ole Golly, the nanny she’s had since she was a baby, is going to get married, she has the same questions:

“What does it feel like to have somebody ask you?” Harriet was getting very impatient.

Ole Golly looked toward the window, folding something absently. “It feels…it feels — you jump all over inside…you…as though doors were opening all over the world…It’s bigger, somehow, than the world.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” said Harriet sensibly. She sat down with a plop on the bed.

“Well, nonetheless, that’s what you feel. Feeling never makes any sense anyway.”

“Harriet felt…”

Much of Harriet the Spy is about what Harriet is feeling:

- When her classmates won’t talk to her or look at her: “Harriet sat down and felt like a lump.”

- When she is further ostracized and can’t use her notebook: “The thoughts came slowly, as though they had to squeeze through a tiny door to get to her, whereas when she wrote, they flowed out faster than she could put them down. She sat very stupidly with a blank mind until finally ‘I feel different’ came slowly into her her…And then, after more time, mean. I feel mean.”

- When she sees that Harrison Withers, one of the subjects of her spying, has gotten a new cat: “And, for some reason, as she walked home Harriet felt unaccountably happy.”

- When Pinky Whitehead, the boy she doesn’t like, does something for her: “She gave him a radiant smile and felt like a first-class hypocrite.”

- When she is with her parents: “That night at dinner Harried suddenly felt like one big ear. Every single thing her mother and father said seemed to be important.”

- When Harriet remembers trying to feel like a bathroom mug: “She sat there thinking, feeling very calm, happy, and immensely pleased with her own mind.”

“A nice life”

Harriet the Spy is about Harriet feeling. It’s about Harriet living as fully and deeply and richly as she can as an eleven-year-old. And she’s aware of this:

“I have a nice life.”

Harriet the Spy and a novel that Louise Fitzhugh wrote ten years later called Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change are wonderfully subversive children’s novels. They are subversive in their refusal to sugar-coat life or to reduce life to a moral or a lesson.

Both books rejoice in the splendid idiosyncrasy of each person, which is to say, each eleven-year-old and each child and each adult and each baby. Both books are honest that life is hard and filled with things that go wrong and filled with a lot that doesn’t make sense.

Feelings don’t make sense — but in a good way.

Any child who doesn’t feel that he or she or they don’t fit in can read Harriet the Spy and find a kindred spirit.

Any adult, too.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.23.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.