Terry Pratchett’s 41 Discworld novels have sold in the millions, so it stands to reason that there must be a lot of people who are fans of Rincewind.

He is, of course, the main character in seven of the books, including three of the first five.

Myself, I find him a one-joke wonder — he survives because he’s such a coward that he runs away all the time. And I find the books about him to be less delightful than most of Pratchett’s other works. There’s still delightful — they’re by Pratchett, after all — but less so.

The problem is that Rincewind, an incompetent wizard who wears a pointed hat emblazoned “WIZZARD,” is always an emptiness at the center of the story.

He doesn’t want to be wherever he is, and his only thought, always, is to flee. So, either he’s fleeing or has fled or is about to flee. As one character says in Interesting Times, Rincewind

“is renowned for being incompetent, cowardly, and spineless. Quite proverbially so.”

Later, in a footnote, Pratchett explains:

Rincewind could scream for mercy in nineteen languages, and just scream in another forty-four.

(By the way, there is a mention late in the novel about Rincewind’s beard — which, to me, seems so wrong. Whenever I read about Rincewind in a Pratchett novel, I picture a very short, nervous, clean-chinned, callow fellow, a perpetual teenager.)

“A puff of warm hydrogen”

“A puff of warm hydrogen”

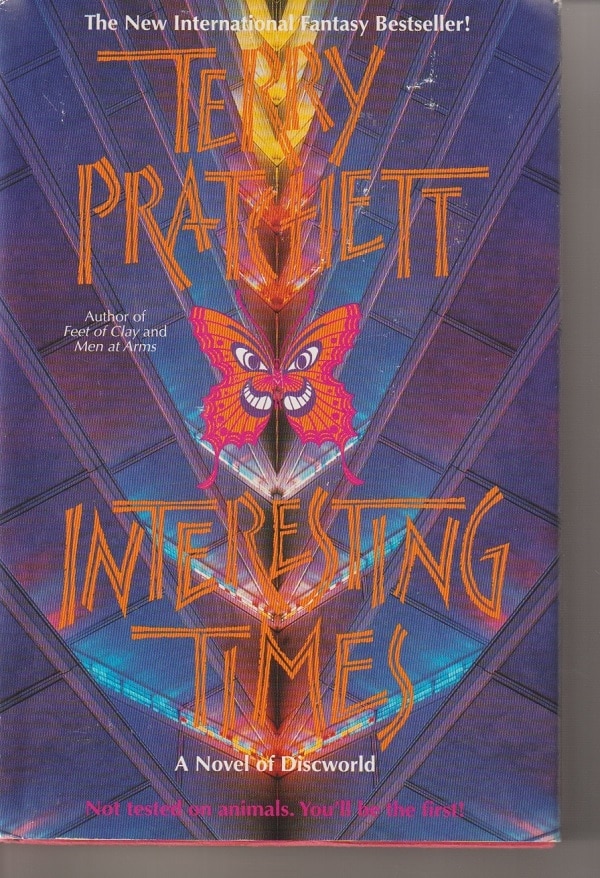

In Interesting Times, Pratchett’s 17th Discworld novel and fifth Rincewind book, he is unusually thoughtful for a few moments:

He was no good at anything else. Wizardry was the only refuge. Well, actually he was no good at wizardry either, but at least he was definitely no good at it. He’d always felt he had a right to exist as a wizard in the same way that you couldn’t do proper maths without the number 0, which wasn’t a number at all but, if it went away, would leave a lot of larger numbers looking bloody stupid. It was a vaguely noble thought that had kept him warm during those occasional 3 a.m. awakenings when he had evaluated his life and found it weighed a little less than a puff of warm hydrogen.

In one of his ancillary Discworld books, Pratchett explained that Rincewind’s function was “to meet more interesting people.” It was an acknowledgement that there wasn’t much he could do with a character whose personality was fully and simply and totally that of a coward.

Stories with “a puff of warm hydrogen” at the core are handicapped from the get-go. At least, that’s what I’ve found in reading the Discworld books.

Mild, milk-toast-y characters

Great writers through history have been successful in fashioning works of high literary merit around mild, milk-toast-y characters. Think of the story Charles Dickens told with David Copperfield, a sweet boy, at the center. As David moves through his life, a kaleidoscope of wildly interesting characters, from Uriah Heep to Miss Murdstone to Mr. Peggotty, happen to him.

In comparison to those who have such huge impacts on his life, David can seem pretty bland. Yet, for all his sweetness, he has a solid character which impels him to try to do the right thing and not only that but to survive — not by fleeing at every turn, but by facing his challenges with an honesty, humility and forthrightness.

I love Pratchett’s books. I love his wit, his silliness, his social commentary and his storytelling zest.

But he is no Dickens. And Rincewind is no David Copperfield.

Old warrior = laugh

Adding to the problems of Interesting Times is the fact that a second major character in the novel is Cohen the Barbarian.

Ghenghiz Cohen is the hero in three of Pratchett’s books — Light Fantastic (1986), Interesting Times (1994) and The Last Hero (2001) — and has spent his life being a hero, i.e., looting ancient ruins, rescuing young ladies, slaying armies of guards and high priests, carousing, having next-morning headaches, engaging in great and mighty adventures with suitable deering-do.

The joke is that, now, he’s old, very old. Yet, in his loincloth and eyepatch and with his spindling legs and diamond dentures, he wields a big sword — and is still successful at it. Nobody takes him seriously until it’s too late.

Cohen was in his late 80s in Light Fantastic, is 90 in Interesting Times and will be even older in The Last Hero.

The idea of a barbarian warrior who refuses to retire is amusing. For me, though, it quickly pales. There’s just not that much to Cohen except the formula: Old guy acting like a young warrior = laugh. In other words, like Rincewind, Cohen is a one-joke character.

The Silver Horde

This worked well enough in Light Fantastic because there were a lot of young, boisterously athletic women around as well as the interestingly organized villain-wizard Ymper Trymon and the live Luggage of sapient pearwood. It also worked despite the active (i.e., toward escape) Rincewind.

In Interesting Times, Cohen is again paired with Rincewind. (Do two one-joke characters make a two-joke book?) But the surrounding cast doesn’t have much zip to it. Pratchett is spending much of the novel satirizing the ancient Chinese empire, seen here as the Agatean Empire on the Counterweight Continent, and either he’s distracted by that or maybe he has just too many other people moving around in the plot for any of them to get much traction.

It certainly doesn’t help that Pratchett adds what, in effect, are five more Cohens to the story — the group of old warriors, called the Silver Horde, who have grouped themselves under his direction. They’re all decrepit like Cohen, but, since there are so many of them, they don’t get to have much, well, character.

The one exception is a sixth member of the Horde, Ronald Saveloy, called Teach, a former school teacher who took up barbarian-ing for the fun of it and has a go at trying to civilize Cohen and the Horde.

“A hat with horns”

Mr. Saveloy, one of the strongest characters in the novel, has something of an inferiority complex in relation to the Horde but, in the end, wins his full stars as a berserker, to the point that:

Mr. Saveloy turned around and looked up at the woman on the horse. It was a big horse but, then, it was a big woman. She had plaits, a hat with horns on it, and a breastplate that must have been a week’s work for an experienced panelbeater.

She’s a Valkyrie who’s there to take him to his final reward which, to his surprise and joy, includes quaffing, carousing and young women.

It’s a touching scene. Really.

“It’s the heroing, see”

Also touching is a scene near the end when Cohen and the Horde are relaxing together, just before the seven of them are going out in front of the city to face armies of something like 700,000 Agatean soldiers.

It is a scene with echoes of Sam Peckinpaugh’s 1969 movie The Wild Bunch, and, when Mr. Saveloy suggests that the best strategy would be to run, Cohen explains:

“It’s the heroing, see. Who’s ever heard of a hero running away? All them kids you was telling us about…you know, the ones who think we’re stories…you reckon they’d believe we ran away? Well, then. No, it’s not part of the whole deal, running away. Let someone else do the running.”

As the Horde talk back and forth in this moment, they become, for once, human and not just cartoonish old farts:

“We’re definitely not going to die, right?”

“Right.”

“I mean, odds of 100,000 to one…hah. The difference is just a lot of zeroes, right?”

“Right.”

“I mean, stout comrades at our side, a strong right arm…What more could we want?”

Pause.

“A volanco’d be favorite.”

Pause.

“We’re going to die, aren’t we?”

“Yep.”

It’s a touching moment. Really.

And it says something about Pratchett’s skill as a writer that I found this scene and much of the last third of Interesting Times well-told, despite the handicaps I mentioned above.

This is a novel that may not be Pratchett’s best. But it’s still Pratchett, and that’s enough for me.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.26.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.