For the past two millenniums, Christianity has so influenced Western society that there is an expectation that a spiritual leader, like Jesus, should be without sin.

In the Catholic Church, the veneration of saints can easily turn these figures into paragons of perfection. And, in the United States, there is a knee-jerk reaction of shock and outrage when a hero, whether secular or spiritual, is found to be flawed, such as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and his adulteries.

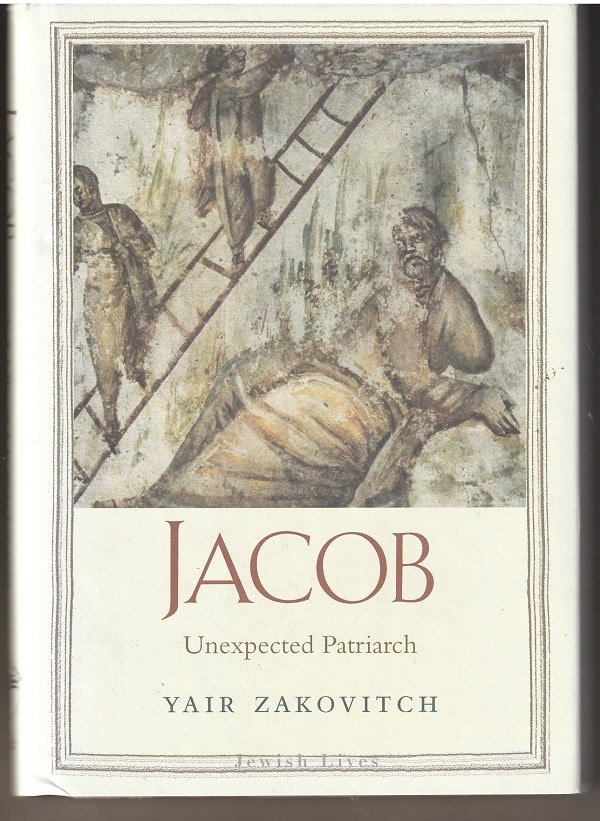

That may have been on the mind of Yair Zakovitch, a Professor of Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, when writing his introduction to Jacob: Unexpected Patriarch, published in 2012 by Yale University Press as part of its rich Jewish Lives series of biographies.

Zakovitch describes himself as fascinated with Jacob while also acknowledging that he was “no model of virtue, which leads us to ask how a figure with a questionable moral code, a man who does not reject availing himself of deceit and dishonesty, came to occupy a prime position among the nation’s patriarchs.”

The answer is that Hebrew Bible isn’t interested in depicting anyone as spotless:

first, because saints are liable to invite veneration, personality cults, and thereby cast a shadow onto their Creator; and, second, and more importantly, because we, who are not flawless, cannot learn from perfect creatures.

“Avoid repeating their mistakes”

The heroes of the Hebrew Bible sin and pay for their sins, and Zakovitch writes:

The astute reader learns from the experiences of the biblical characters to avoid repeating their mistakes and thus precludes inviting punishment on himself or herself.

So, yes, Jacob is a sinner.

He takes advantage of his hungry, rough-hewn elder brother Esau when the hunter comes home famished and asks for some stew. Jacob demands Esau’s birthright in exchange for the stew, and the less-than-clever brother agrees.

Later, Jacob masquerades as Esau to trick his father Isaac into giving him the blessing that is due to the first-born.

And, much later still, Jacob, now old and frail, dotes so much on his 11th son Joseph — the first born of his favorite wife Rachel — that the other brothers, his sons by another wife and two maidservants, send the teenager off to slavery in Egypt.

“The richly colored mosaic”

The retribution Jacob suffers is apt.

He is tricked by Rachel’s father Laban into marrying the girl’s sister Leah before he can marry his true love, and then he is forced to work 20 years for Laban, being cheated out of his wages ten times. When he finally leaves to return to Canaan, the father-in-law tries other tricks.

And, as a father, his favoritism for Joseph brings him deep grief because the other sons lie to him, saying the boy was killed by a wild animal and showing him Joseph’s blood-stained garment as proof.

Yet, Jacob also is blessed by God with a vision of the stairway for angels between heaven and earth and is the victor in a wrestling match with someone from God, a man or an angel.

He is, as Zakovitch writes, a key figure in the Lord’s on the holy design:

The last of the nation’s patriarchs and the father of twelve sons and one daughter, Jacob stands at the junction at which the life of one family becomes transformed into the history of a nation. The varied traditions that express and serve different motives, and the richly colored mosaic created by their combination, teach us how Jacob’s actions, his failures, and God’s judgment all served the great, divine plan of transforming Jacob into Israel, the patriarch of the people of Israel.

Often-awkward traditions

Jacob: Unexpected Patriarch is rooted in Genesis, but it is far from a regurgitation of Bible verses.

Zakovitch details the often-awkward presence together in those verses of various traditions — i.e., stories and understandings about what happened. Although established as canonical, the accounts in the Hebrew Bible retain these earlier and later interpretations, extending even into the New Testament.

Consider, for instance, the story of the rape of Dinah, Jacob’s only daughter, by the son of the leader of the city of Shechem. The young man, also named Shechem, then falls in love with the girl and wants to marry her.

When Jacob learns of this atrocity, he does nothing. And Zakovitch asks why that is — what was the author wanting to say or not say by having the family leader on the sidelines?

What Genesis says is that Dinah’s brothers decide to take revenge by trickery and violence. In marriage negotiations, they insist that, for religious reasons, all the male Shechemites must be circumcised. Those Shechemites agree, and, then, while they are weak and in pain from their wounds, they are all slaughtered and their homes are ransacked.

Inconsistencies in the story

But there are four inconsistencies in the story — “ ‘rough spots’ that are evidence of the story’s complex and gradual composition.” In one place, for example, the account says that two of Dinah’s older brothers, Simeon and Levi, did all the killing, but, in another place, it says all the brothers took part in the pillaging.

This, for Zakovitch, indicates that the exclusive blame of the two was a later addition, as were the other inconsistencies.

Once those additions are taken out, the story is much different. There’s no rape of Dinah. Shechem falls in love with her and starts marriage negotiations. The brothers demand the circumcision of the males and then kill them all. Zakovitch writes:

The verses that introduce rape and defilement into the story were apparently added to justify the brothers’ violence.

In some cases, the additions were made to fit this story into events that happened before and later. But there are nuances upon nuances here, and Zakovitch delves into each wrinkle of tradition to get a sense of the depths of the story.

“Well, which is right?”

It is a story about a rape and not about a rape. It is about righteous violence and about greedy violence.

It keeps Jacob at a distance from the action so he’s not tainted by the violence and greed, and it suggests that only Simeon and Levi were to blame for the massacre. And, yet, at the very end, it makes Jacob look bad and the two brothers look good.

This is when Jacob complains to the two for the violence, not on ethical grounds, but because

“You have brought trouble on me, making me odious among the inhabitants of the land…I will be destroyed.”

To which, the sons say,

“Should our sister be treated like a whore?”

After reading Zakovitch’s discussion of this section, a reader might sit befuddled, demanding, “Well, which is right?”

Richness and mystery

My understanding of this example and of the other similarly nuanced scenes in Jacob: Unexpected Patriarch is that, in some deep way, they are all right.

Of course, the rape is the canonical story. It’s in the book. But there is enough other stuff in and around it to suggest that other stories could be true — may, indeed, have more truth to them.

For me, the bottom line here and in all the rest of Zakovitch’s book is that the biblical story of Jacob is unlike a modern history book in which facts are marshalled, presented and argued. Instead, it is like a work of art that suggests many things, some of which will seem to be mutually exclusive.

Zakovitch calls it a mosaic of many traditions.

A mosaic, remember, is made up of tiny pieces of colored stone with sharp edges. Nonetheless, when all those tiny stones are put together, they create an image — but it’s an image with blurred lines. It’s an image that hints rather than one that replicates.

There is in the stories of Jacob much more than meets the eye at first glance. Deep study, as Zakovitch has brought here, reveals many reverberations and even dissonances.

It brings a richness and mystery to the stories of Jacob. And Zakovitch shows himself to be a most helpful, intelligent and sensitive guide through this richness and mystery.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.3.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.