I have a bone to pick with people who want to talk about “young adult” books. To me, this has more to do with the need of a bookstore, say, or a library to categorize and organize volumes, and less to do with the books themselves and their audience.

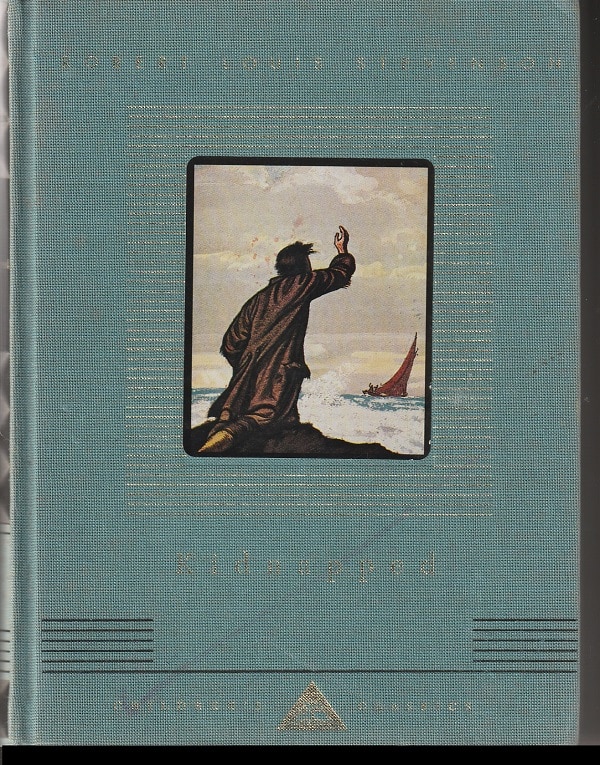

Kidnapped, published in 1886 by Robert Lewis Stevenson, is a classic in that category, described as a “boy’s novel” or a “boy’s adventure.”

It is a proto-“young adult” novel about the kidnapping of an 18-year-old Scottish boy, David Balfour, for sale into slavery in the American colonies. He undergoes great hardships and threats to his life as he struggles his way back to win his inheritance, meeting several historical figures including the irrepressible Scottish rebel Alan Breck Stewart. The two spend much of the novel being hunted, and they become close friends.

Kidnapped is a rollicking tale that, yes, has beguiled generations of boys. Yet, the fact is that girls can find — and have found — the book fascinating. Adults too.

The late Hilary Mantel, author of esteemed historical fiction, including the immensely popular trilogy of novels centering on the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell in the court of Henry VIII, told the Guardian in 2005 that she was enthralled by the Stevenson novel as an eight-year-old.

“It made a lot of sense, when Davie finds himself marooned in the wild country, where the previous rules don’t obtain. I just knew this was what a story should be like. It was the model that was always in my head. Stevenson takes the reader by a short route from one point of suspense to the next. Even as a very small and unsophisticated reader I understood the perils Davie was entering into.”

Henry James was captivated by the book, particularly Alan Breck Stewart whom he described as “the most perfect character in English literature.” Other adult fans of the book and of Stevenson have included Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway and Vladimir Nabokov.

Entertainment and literature

Most novels are written to be entertainment. That’s why there are so many genres or categories, whether young adult or science fiction or thriller. Readers pick up a genre book for the fun of it — for its ease. They know what to expect, and they don’t expect to do a lot of heavy-lifting.

Some novels, though, are literature. They are more challenging and rewarding, seeking to rise above the run-of-the-mill and attempt to create art.

They do this in the way the story is told, i.e., style, language and creativity, and in the psychological depth of the characters and their actions. The author of a literary novel — it’s odd in a way that there is such a category — eschews the superficial and stereotypical and attempts to get at what makes humans tick.

To call George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four a science-fiction novel is to ignore its literary excellence. Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice isn’t a romance novel although it’s been the model for two centuries of them. Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is about a murder but shouldn’t be thought of as a murder mystery.

The same is true, I think, with Kidnapped.

“A clay-faced creature”

For instance, consider the way David Balfour — the narrator of the novel — describes his uncle Ebenezer when first they meet at the family house in Cramond, outside of Edinburgh:

He was a mean, stooping, narrow-shouldered, clay-faced creature; and his age might have been anything between fifty and seventy….He was long unshaved; but what most distressed and even daunted me, he would neither take his eyes away from me or look me fairly in the face. What he was, whether by trade or birth, was more than I could fathom; but he seemed most like an old, unprofitable serving-man, who should have been left in charge of that big house upon board wages.

As a description, that savors more of Charles Dickens than Robert Ludlum or Ian Fleming.

In most adventure stories, the villain — and Uncle Ebenezer turns out to be a right villain — is introduced in clear, straight-forward language, applied with strong simple brush strokes, identifying him as a bad guy. Think of the James Bond opponent Doctor Julius No, a reclusive Chinese-German scientist with a Napoleon complex.

Stevenson, by contrast, goes deeper. While suggesting that Uncle Ebenezer has few if any redeeming features, he particularizes the character. This oldish man is uniquely himself, and his appearance and actions hint at complexities in his life story.

David’s description of his uncle echoes, for me, David Copperfield’s depiction of Uriah Heep, the law clerk of Mr. Wickfield, who first appears at a small window as “a cadaverous face”:

The low arched door then opened, and the face came out. It was quite as cadaverous as it had looked in the window, though in the grain of it there was that tinge of red which is sometimes to be observed in the skins of red-haired people. It belonged to a red-haired person — a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older — whose hair was cropped as close as the closest stubble; who had hardly any eyebrows, and no eyelashes, and eyes of a red-brown, so unsheltered and unshaded, that I remember wondering how he went to sleep.

He was high-shouldered and bony; dressed in decent black, with a white wisp of a neckcloth; buttoned up to the throat; and had a long, lank, skeleton hand, which particularly attracted my attention, as he stood at the pony’s head, rubbing his chin with it, and looking up at us in the chaise.

“Stumbling like babes”

Similarly, adventure stories usually depict the hero with seeming superhuman strength and stamina, climbing mountains or scaling buildings or racing through sewers with vim and vigor and nary a drop of sweat.

By contrast, Stevenson brings the reader deep into the exhausting experience that David and Alan Breck Stewart have, trying to stay free and get to Cramond.

In fact, David himself notes that authors don’t seem to have ever been wearied “or they would write of it more strongly.” And he goes on:

I had no care of my life, neither past nor future, and I scarce remembered there was such a lad as David Balfour. I did not think of myself, but just of each fresh step which I was sure would be my last, with despair….

Day began to come in, after years, I thought; and by that time we were past the greatest danger, and could walk upon our feet like men, instead of crawling like brutes. But, dear heart have mercy! what a pair we must have made, going double like old grandfathers, stumbling like babes, and as white as dead folk.

Never a word passed between us; each set his mouth and kept his eyes in front of him, and lifted up his foot and set it down again, like people lifting weights at a country play; all the while, with the moorfowl crying “peep!” in the heather, and the light coming slowly clearer in the east.

This is evocative for any reader who has ever felt pushed to the brink by physical exertion — and brings the experience alive for any reader who has never been driven to such extent.

“This is a great epic”

One of the delights of literature are the allusions to earlier works that a writer includes, and a particularly apt one comes near the end of Kidnapped.

The two fugitives have finally gotten to Cramond where David finds a way to meet the family lawyer, Mr. Rankeillor, and relate his tale. The lawyer, initially skeptical, tests the young man enough to realize that he’s speaking the truth.

“Well, well, this is a great epic, a great Odyssey of yours. You must tell it, sir, in a sound Latinity when your scholarship is riper; or in English if you please, though for my part I prefer the stronger tongue. You have rolled much; quae regio in terris — what parish in Scotland (to make a homely translation) has not been filled with your wanderings? You have shown, besides, a singular aptitude for getting into false positions; and, yes, upon the whole, for behaving well in them.”

These sentences do several things. They dovetail with earlier references to indicate that the lawyer is more than a bit pedantic and yet not stuffy. There’s a liveliness to his language despite his weakness for dropping Latin phrases into his speech.

In addition, Mr. Rankeillor sums up the story of Kidnapped in a perceptive single sentence: “You have shown, besides, a singular aptitude for getting into false positions; and, yes, upon the whole, for behaving well in them.”

And he compares David’s long and arduous journey to Homer’s great Greek epic: “this is a great epic, a great Odyssey of yours.”

Since the Odyssey was first written down thousands of years ago, authors have used it as a model for modern stories.

That’s what Stevenson did, with David in the role of Odysseus and with a nice twist at the end. Instead of David finding a loyal Penelope upon his return, he is able to prove that his uncle is as disloyal as they come.

So, don’t call Kidnapped a boy’s novel. It’s literature, plain and simple.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.6.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.