Anne Kraatz initially published her book Lace: History and Fashion in French in 1988 and then helped with the English version from Rizzoli the next year with a translation by another expert on lace, Pat Earnshaw.

The sumptuously illustrated, large format book is filled with 180 illustrations, 92 of which are in color, and most are close-up views of various pieces of lace, going back to the sixteenth century. Kraatz, who had overseen several museum shows about lace in earlier years, writes in her preface:

My conversations with the public during these exhibitions had convinced me that they wanted precise information about lace rather than anecdotes: to learn the technical and design characteristics of each, to be able to place the great laces in their social and historical contexts, and to distinguish antique laces from copies.

Her audience spoke, and Kraatz responded with a work that is a rich treasury of very specific, very nuanced information on how all sorts of lace have been made over the centuries and where those types of lace were made and how, if not for home use, they were marketed and who bought and wore those many kinds of lace.

Her audience, in other words, are people for whom lace is a professional occupation or an intense personal preoccupation — tailors, manufacturers, designers of all stripes (fashion, furniture, etc.), consumers, art historians and so on.

I am not her audience, given my deep ignorance of how to create things with fabric, particularly in this case lace, and my status as simply a rubbernecking tourist in a world far from my own.

Still, I enjoyed Kraatz’s book.

Like fingers moving over the lace

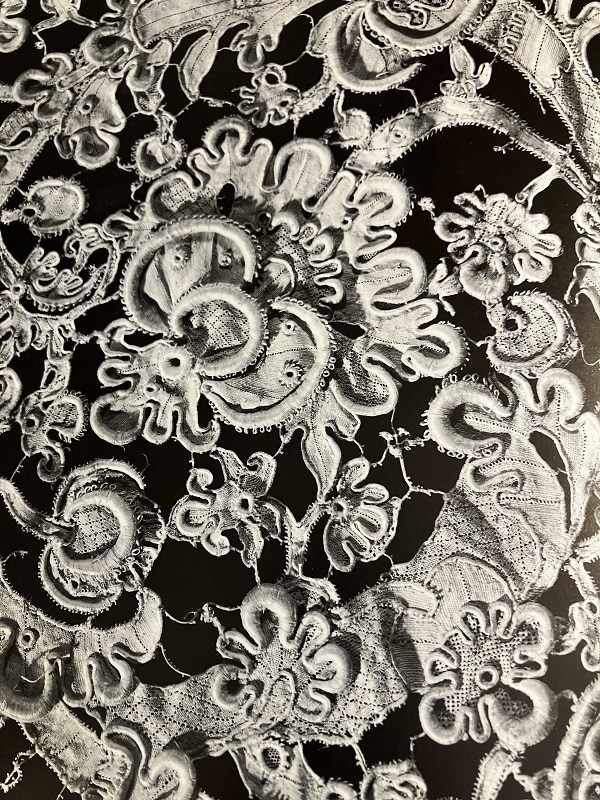

For instance, on page 34, Kraatz offers a full-page close-up of piece of 17th century Venetian gros point, needle-made lace that I can almost feel.

What I mean is that it exhibits such sharply different thickness of fabric — from very thin to very thick — that my eyes act like my fingers in moving over the lace. The caption describes this piece as a “typical example of the type of lace in which the sculptural effect is ideally suited to masculine clothes.”

That points up two aspects of lace.

The wearing of space

The “sculptural” effect of lace doesn’t only have to do with the thickness and thinness of the fabric and the contrast between the two.

It also has to do with the lace itself which is, essentially, the wearing of space.

Lace, by definition, is about emptiness. The cloth is created in patterns around this emptiness. It recalls sculptures existing in a space — and, for that matter, architecture as well. This physical thing, whether a Rodin figure or a Mies van der Rohe building or a shawl of lace, has its reality in its relationship with what isn’t there.

So, in the illustration of the Venetian gros point, my eyes aren’t only feeling the texture of the thin and thick areas of the fabric. They are also feeling the emptiness — the absence of cloth — that is part of the pattern.

“Magnificent laces”

The other aspect is the heavy use of lace by men throughout the early centuries of its history, something that Kraatz notes in the opening words of her book’s preface:

Today the word ‘lace’ evokes in most minds an image of women: the skilled and diligent women who make it, and the charming and frivolous ones who wear it. The reality of lace is quite different. It was not at first particularly feminine, since men wore almost more of it than women…

Consider this image of Nicolas de L’Hôpital, duc de Vitry, from about 1645, in which lace is used as a contrast to armor:

Kraatz’s caption notes that his collar is “edged with a wide bobbin lace,” i.e., lace made with bobbins, not needles, “decorated with stylized flowers,” worn over ceremonial armor emblazoned with trophies of war. In her text, Kraatz writes of 17th century fashion:

Masculine elegance decreed magnificent laces on armor. The most severe militia, and the least suspect of ambiguity, posed unhesitatingly for their portraits with great collars of lace advantageously displayed over breastplates of burnished steel.

Among civilians, the masculine shirt became voluminous in the 1630’s, and called for deep cuffs of lace which concealed half the hands.

Children, she adds, of both genders wore as much lace as their parents.

In America

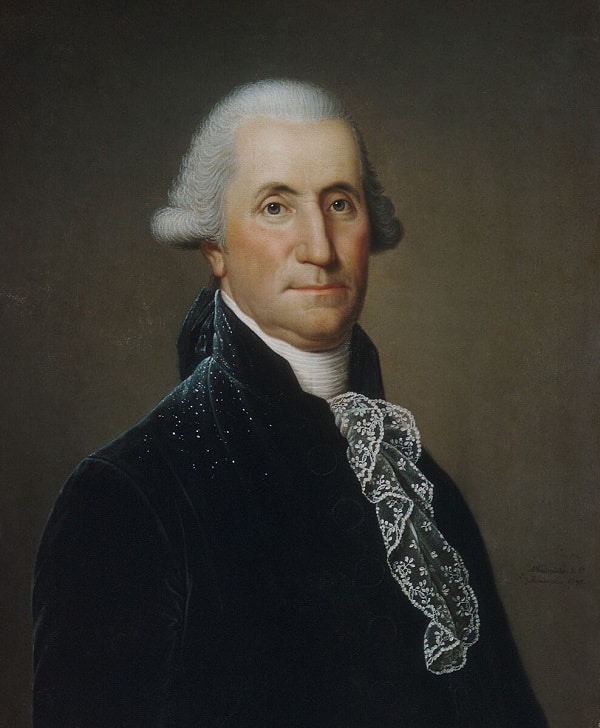

Lace for men was still popular in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, in 1794, during his second term as President, George Washington was painted by Adolph Ulrich Wertmuller with a jabot of Alencon lace. Kraatz reports that this is the only known image of Washington wearing lace.

One final note on the masculine use of lace: Some vestments of Roman Catholic priests and some Protestant clergy have long featured intricately woven lace.

“Supremely virtuous”

And, when it comes to women, is there another form of cloth/fabric that carries so many associations? Kraatz writes:

Lace has acquired, over the centuries, a legendary evocative power. It stands for purity — what [is] more virginal than a white wedding veil — and for eroticism — what [is] more seductive than black lace lingerie?

And not only lace itself, but also the making of lace which, in the early 1900s, was seen by some French political figures as a buttress against social unrest, as Kraatz notes:

Lace had long been thought of as a symbol of femininity, but more and more, at the beginning of this century, lacemaking came to be regarded as a supremely virtuous feminine occupation, enabling women to say at home while earning housekeeping money.

“No longer a woman”

By staying at home, women were being “supremely virtuous” because they weren’t looking for work in factories where jobs were thought to belong to men.

In addition, by staying at home and making lace, they retained their womanhood. At least, that’s how Andre Mabille de Poncheville, a journalist, poet and lawyer, saw it in 1911:

“If one bemoans the introduction of women into manufacture, it is not that their material condition there is very bad….It is that woman, having become a worker, is no longer a women.”

Kraatz notes that this was an argument that women did not wish to hear.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.21.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.