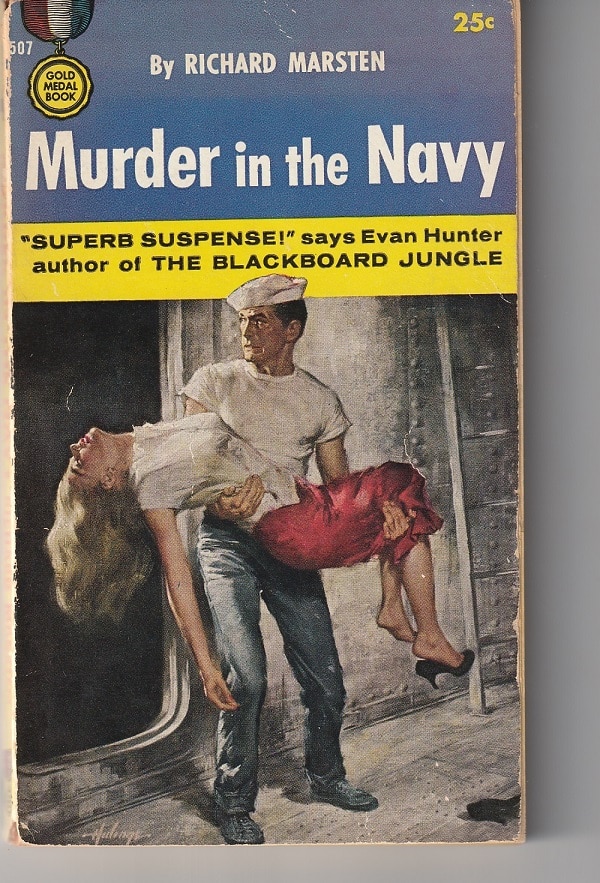

In the 1955 novel Murder in the Navy, the killer is an evil presence operating in the shadows. But he’s not hidden from the reader, even though his name isn’t known until the very end.

In the opening scene and at several other points in the book, the reader is taken inside the killer’s mind.

And, although this Navy sailor is responsible for three murders and maybe another very soon, he is still a human being with fears and other emotions that a reader can relate to, if not endorse. Late in the book, the reader’s told:

He didn’t like thinking about murder, but he had to admit it got a little easier each time. Especially when you got away with it. And getting away with it was almost as easy as the actual killing. Now there was a disgusting word. Well, that’s what it was. A rose by any other name…Jesus, but Jean smells sweet. Not a perfume smel,l no, just a good soap smell, clean, like everything about her.

So, we have no cardboard bad guy, but someone who not only kills but also quotes Shakespeare and can appreciate “a good soap smell.” In other words, a human being.

Hunter and McBain

The man who wrote Murder in the Navy had been born 29 years earlier in New York under the name Salvatore Lombino. But that name doesn’t appear anywhere on the cover or inside the book.

I interviewed Lombino several times in the course of his long, successful, remunerative writing career, and, as far as I can tell, the name Lombino never appeared on any of his books.

Instead, his books — the more seriously literary ones — would identify the author as Evan Hunter, the name Lombino took as his legal name in 1952. There were about 30 of those.

Then, there were others, genre works of the police procedural school, that he’d publish under another name, Ed McBain. Between 1956 and 2005, there were more than 50 installments of McBain’s 87th Precinct mysteries, focusing on the squad of detectives in one station house of a city much like New York.

Hunter and McBain together

In 2000, in a playful publishing stunt, Hunter and McBain were listed as the co-authors — complete with side-by-side photos on the back of the cover jacket — for Candyland. It was the story of a crime, written by the Hunter persona, and the solving of the crime, written by the McBain persona.

Beyond this, Hunter-McBain used a variety of other pseudonyms for some other crime and science fiction novels, most frequently Richard Marsten (eight from 1953-1959). (In addition, in the 1950s, for his magazine stories, he wrote under a variety of names, including, on occasion, S.A. Lombino.)

Hunter told me that he dropped Lombino and took the pretty WASPish name of Evan Hunter because, at the time, ethnic names weren’t very attractive to publishers. Also, he never felt like a Sal.

He decided to use McBain because the series was aimed at a popular audience with a repeating cast of characters, unlike his Hunter books which were always more ambitious and always stretch in terms of the need to create new characters and find his authorial method each time.

“It’s hard to write an Evan Hunter novel because I really am starting from scratch,” he told me. “I’m assuming a new voice each time. The McBain voice is set.”

The sense I got was that, although Hunter was proud of his popular 87th Precinct mysteries, he had more pride of his authorship in his serious novels under his legal name.

And I suspect he would be irritated that Wikipedia lists him under his Ed McBain pseudonym rather than his real legal name of Hunter. I know he complained to me that, here and there, a Hunter novel would be reissued under the McBain byline, irritating him to no end.

“SUPERB SUSPENSE”

I’ve owned a copy of Murder in the Navy for more than a quarter of a century. I’m sure I had it for a while before January, 2001, when I did a phone interview with Hunter about Candyland for the Chicago Tribune.

The thing is, the paperback of Richard Marsten’s Murder in the Navy included, across the top of the front cover, a great blurb from the writer of a big bestseller the previous year, The Blackboard Jungle — “SUPERB SUSPENSE!”

That writer was Evan Hunter.

“I did that pretty much as a gag,” Hunter told me.

“What’s his game?”

Still, the fact is that Hunter was right about Marsten’s book. It is filled with suspense, and the reason for that is Hunter’s ability to make his characters seem real.

In a career in which Hunter, McBain et al published at least 120 novels as well as assorted other books, Murder in the Navy was the author’s ninth work when he was still learning his craft.

In some ways, that’s evident from storytelling clunkiness that pops up here and there, but, overall, Hunter was already displaying his writing skill, such as his use of the technique of taking the reader inside the minds of individual characters.

The killer was one, as I’ve noted above. But there were others, such as Greg Barter, a pharmacist’s mate at the hospital who suspects the killer is a malingerer:

What was his game? That was the big question, all right. The guy in 107 had a game, as sure as God made little green apples….

Then what’s his game?

I don’t know, Greg admitted. But I’m sure as hell going to find out.

It turns out he does find out — to his great chagrin.

A kinship

Then, there’s Lt. Chuck Masters who is ordered to investigate the murder of a nurse on his ship the USS Sykes in Norfolk, Va., and then is ordered to forget about it when the FBI turn up a likely suspect.

He doesn’t agree, but he’s not spending all of his time just thinking about it. He’s on a train to Atlantic City in one scene:

In all his experience with trains, he had never achieved that simple goal of making himself comfortable, and this experience, he silently reflected, was no different from any of the others. The people who designed trains, he was sure, were the same people who designed such things as electric chairs and subterranean torture chambers.

And, then, there’s the girl he’s sweet on and who, unknown to him, is the romantic target of the killer, Jean Dvorak. In one scene, as Masters is on his way north, she is trying to figure out her thrilling and confusing relationship with him:

Now let us draw up the reins, Miss Dvorak, she warned herself. This may just be a grand little fling for the good lieutenant, and if it is, he’s going to be sadly disappointed.

It doesn’t seem as if he feels that way, but there’s really no way of telling. Not yet, there isn’t. And he has been a perfect gentleman, except for his kisses. No perfect gentleman kisses that way.

Murder in the Navy was one of Hunter, McBain et al’s earliest novels, but it works very well, even seven decades after it was published.

Because of Hunter’s skill, the reader gets to know and to find kinship with Greg and Masters and Jean Dvorak — and even the killer. And that’s something that will keep someone reading all the way to the end.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.4.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.