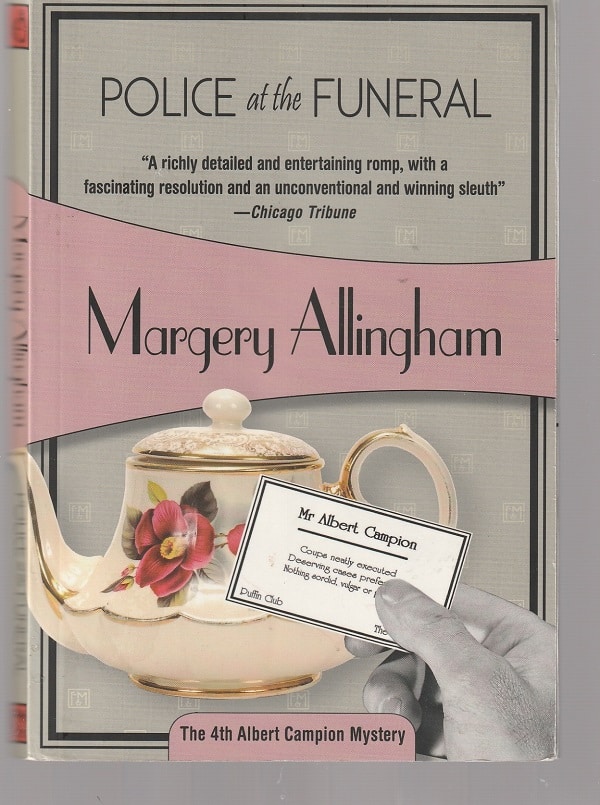

Margery Allingham’s 1931 mystery Police at the Funeral is a truly excellent example of the genre — briskly told, peopled with interesting characters, investigated by a quirky non-detective and concluded with an out-of-left-field solution that is both utterly surprising and utterly satisfying.

It starts when, in London, a young woman named Joyce Blount approaches Albert Campion, a free-spirited upper-class gentleman in his 20s, for help in finding her missing Uncle Andrew. Campion, who has made a minor name for himself as an amateur (almost inadvertent) crime solver, attended Cambridge with Joyce’s fiancé Marcus Featherstone.

It’s in Cambridge that Joyce now lives at the large old home, known as Socrates Close, run with a steely will by her 84-year-old Great-Aunt Caroline Faraday.

Living there for free but constrained by Caroline’s iron hand are four bickering relatives well past middle-age: Caroline’s three children, William, Julia and Kitty, and her nephew, the missing Andrew. And, of course, a handful of longtime servants.

Soon enough, Andrew is found dead, his legs and hands tied and a huge bullet hole in his forehead. Then, another household member dies of poison, but was it self-inflicted or was the death murder?

“Very beautiful”

At every twist and turn, the reader finds delectable discoveries, such as a single huge animal-like, naked human footprint in a garden, and a blackmailing cousin with a deep secret, and a runic sign in red on a study window, and a lovelorn letter, and a tell-all memoir. And there is a constant refrain about the plain evil that seems to be afoot in the house.

Beyond that, there’s even a touching piece of jewelry that Allingham describes this way:

On a nest of quilted pink silk lay a heart-shaped miniature. It was a delicately lovely piece of work, the frame set with small rubies and brilliants.

On the ivory was a portrait of a girl.

Her sleek black hair was parted in the center and arranged in small curls on either side of her face. Her dark eyes were grave and large, her small nose straight, her lips smiled. She was very beautiful.

“Overfed” and “Act of God”

As that shows, Allingham is a highly entertaining writer. Here’s another example:

The dining-room was a large square apartment with crimson damask wallpaper and red plush curtains. Dark paint and a Turkey carpet did not tend to brighten the scheme of decoration, and, as Joyce remarked later, one felt overfed upon entering the room.

The large oval table was a veritable skating-rink of Irish damask, and upon it there was set out every night a magnificent array of plate, the cleaning of which occupied the entire life of an unfortunate small boy in the servants’ quarters.

And another: the words of an exasperated police investigator when the complications of all the skullduggery reach their most convoluted:

“What a rotten unsatisfactory case this is! I knew it would be the moment I spotted that coincidence at the beginning. I’m not a superstitious man, but you can’t help noticing queer things when they happen over and over again. If I had my way about this case I’d write “Act of God” across the docket and shut it up in a drawer.”

“Like a small eagle”

For my money, though, Allingham’s best work comes when she is writing about Great-Aunt Caroline, “an old woman of striking appearance without any of the ugliness which great age so often brings to a masterful countenance.”

When Caroline shows up in the novel, about a quarter of the way into the book, silence greets her appearance in the doorway, as Allingham writes:

She was very small, but surprisingly upright. It seemed to Mr Campion’s fascinated gaze that the major portion of her body was composed of some sort of complicated structure of whale-bone beneath her stiff black silk gown. Around her tiny shoulders she wore a cape of cream rose point, and the soft web was caught at her throat by a large cornelian brooch. Her serene old face, in which black eyes gleamed as brightly as ever they had done, was surrounded by a short scarf of the same lace worn coif-fashion and held in place by a broad black velvet ribbon….

At the moment she held a thin black walking-stick in one hand and a large blue cup and saucer in the other.

She looked like a small eagle as she stood in the doorway glancing from one to the other of them standing before her like the naughty children she considered them.

Early in the novel, Joyce describes Caroline to Campion as “the most live person in the household…[who] still runs the show rather grandly, like Queen Elizabeth [—i.e., Queen Elizabeth I, the second one wouldn’t become queen for another two decades—] and the Pope rolled into one.”

An imperfection and a subtle piquancy

One imperfection in Police at the Funeral has to do with its age.

Modern readers are likely to be discomfited by a rather casual use of the n-word, mentioned in passing, a use acceptable in 1931 Britain (although much less so in the United States, even then).

Similarly, a key plot twist is rooted in deep prejudice. This can be viewed with outrage by the reader, or, perhaps, with the understanding that attitudes and insights change over time. This is not to say that such bias was ever right. It’s always been wrong.

Finally, on a more positive note, there is a minor aspect to Allingham’s novel that gives it a subtle piquancy.

When Campion first sits down alone with Caroline, she says, “’And now, let me look at you, Rudolph. You’re not much like your dear grandmother, but I can see the first family in you.”

This is the first of several references by Caroline that suggest that the young man is actually a member of the royal family, living incognito under the name of Campion. She is an old friend of his grandmother and explains,

“My dear boy, very old ladies only gossip among themselves. I shall not expose you. I may say I quite agree with your people in theory, but, after all, as long as that impossible brother of yours is alive the family responsibilities are being shouldered, and I see no reason why you shouldn’t call yourself what you like.”

Patrick T. Reardon

8.4.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.