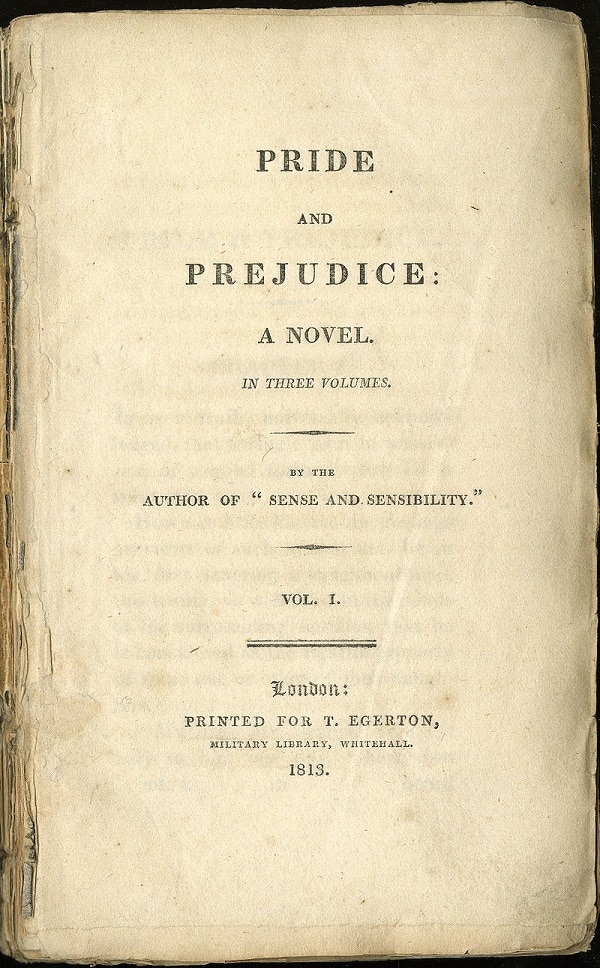

For me, the high point of my reading of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice came near the end of the 1813 novel when Elizabeth Bennett receives a letter from her aunt, Mrs. Gardiner.

But, before I get to that, let’s go about a hundred pages earlier to one of English literature’s great scenes: The handsome, immensely rich and seemingly aloof Fitzwilliam Darcy, out of the blue, asks Elizabeth for her hand in marriage, even while asserting that, to do so, he has had to overcome his powerful reservations about the lowliness of her family and its place in the world.

His sense of her inferiority — of its being a degradation — of the family obstacles which had always opposed to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

To this, Elizabeth responds with a dignified and, she feels, righteous anger, telling her would-be suitor that she has had a profound dislike of him ever since the delightfully charming George Wickham explained to her how Darcy had ruined his life, and that her dislike has just recently been heightened upon learning that Darcy had convinced his friend Charles Bingley to break off his courtship of Elizabeth’s sweet older sister Jane.

Darcy was, she told him in no uncertain terms, “the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed upon to marry.”

Darcy’s letter

The next day, as Elizabeth is walking, Darcy approaches and hands her a long letter responding — with straight-forward respect and deeply apparent restraint — to her two charges against him.

In his defense, he details how Wickham, the son of his late father’s steward, was a wastrel who quickly squandered his inheritance and then tried to elope with Darcy’s 15-year-old sister Gloriana in order to lay claim to her substantial dowry.

As for her second charge against him, Darcy acknowledges that, yes, he did counsel Bingley against Jane, believing that she was indifferent to his attention and feeling that her family had constantly shown a “total want of propriety” by talking and acting as if a marriage of Bingley and Jane were a fait accompli.

This totally unexpected and, in its way, humble letter was from a man whom Elizabeth had strongly disliked for what he’d done to Jane and what she understood he’d done to Wickham — and a man who had put her into an exquisitely uncomfortable position by startlingly wooing her while also emphasizing her inferiority.

Nonetheless, Elizabeth did not read Darcy’s letter with the rage of a wronged woman.

Instead, she did so with the open-heartedness of a lover of truth, with a willingness and desire to understand the world and the people in it, with a courageous intellectual and emotional vulnerability.

She grew absolutely ashamed of herself — Of neither Darcy nor Wickham could she think without feeling she had been blind, partial, prejudiced, absurd….

When she came to that part of the letter in which her family were mentioned in terms of such mortifying, yet merited reproach, her sense of shame was severe.

The justice of the charge struck her too forcibly for denial, and the circumstances to which he particularly alluded as having passed at the Netherfield ball, and as confirming all his first disapprobation, could not have made a stronger impression on his mind than on hers.

Elizabeth recognized her own foolishness in believing the fast-talking Wickham and in ignoring the gaucherie of her family.

“Her heart did whisper”

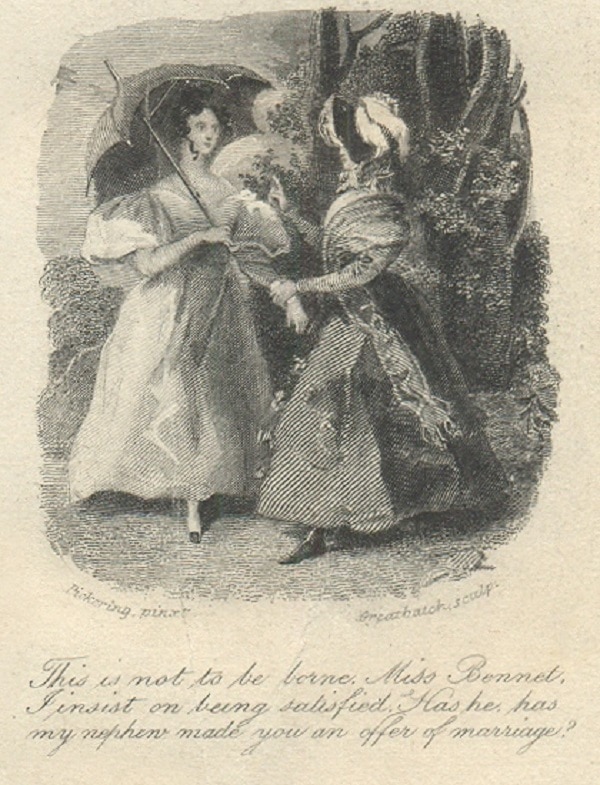

Many chapters later, Elizabeth receives the letter from Mrs. Gardiner. In it, her aunt relates how Darcy — while seeking total anonymity — arranged to save the reputation of Elizabeth’s youngest sister, 16-year-old Lydia.

This flighty, giddy teenager, swooning at soldiers in uniform, had run away with Wickham, asserting her love for him even if, for him, this affair was no more than a passing thing. Of course, as a 19th century man, his reputation would suffer little from the episode while Lydia’s life in respectable society would be over.

Suddenly, though, after much negotiation seemingly carried out by Elizabeth’s uncle Mr. Gardiner, Wickham agreed to wed Lydia and accept an annual payment to keep the couple financially stable. But it wasn’t Elizabeth’s uncle, it was Darcy who, at great financial and emotional cost, paid off Wickham’s huge debts in order to coerce the wayward young man — “the man he most wished to avoid,” Elizabeth acknowledges — to do right by Lydia.

Since Darcy’s botched wedding proposal and his elegantly restrained letter, Elizabeth had been growing in her regard for him as she learned more about him and saw him loosening up his prideful demeanor.

Indeed, in this case, she recognizes, Darcy “had done all this for a girl whom he could neither regard nor esteem,” the deeply silly, thoughtless and self-obsessed Lydia.

As Elizabeth ponders this, Austen writes:

“Proud of him”

And not only that:

She was even sensible of some pleasure, though mixed with regret, on finding how steadfastly both [Elizabeth’s aunt] and her uncle had been persuaded that affection and confidence subsisted between Mr. Darcy and herself.

Yet, Elizabeth is a clear-eyed realist, and she knows that it is probably too much to think that he has affection “for her — for a woman who had already refused him.” Even more, she knows that for Darcy to pursue any affection — if there were any — would, if followed through, make him brother-in-law of Wickham, an abhorrent thought for him.

Elizabeth recognizes with painful objectivity the great obligations that she and her family owe to Darcy, debts that can never be repaid or, given his request for anonymity, even mentioned.

So, here she is, a 20-year-old woman who, in the space of a couple months, has turned down two marriage proposals — one from the buffoonishly self-important William Collins and the second from Darcy, a man whom she intensely detested at the moment of his astonishing offer but whom she has come to admire from a distance, even as, it seems, he will never again look her way.

She could mope and wail. Lydia would mope and wail. But Elizabeth is made of sterner stuff, and Austen writes:

For herself she was humbled; but she was proud of him. Proud that in a cause of compassion and honour, he had been able to get the better of himself.

Truthful enough

These, to my mind, are perhaps the key sentences of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

Elizabeth finds herself on the outside of Mr. Darcy’s life, looking in. In the course of their often-contentious relationship, she has deeply hurt him, and he has deeply hurt her. Yet, she doesn’t wallow in self-pity. She is willing to accept her role in what has happened between them, and, at this moment, she is not thinking about herself.

She recognizes that Darcy has done a good turn to her and her family. He has given them an otherwise unobtainable gift, and she is humble to receive such a gift.

And here’s the key thing:

She was proud of him.

This, it seems to me, gets to the core of Austen’s novel.

There is a pride such as Darcy exhibited at the start of the novel that is self-referential and close-minded. It is a prejudice. Elizabeth’s disdain for Darcy early on was its own form of prejudice.

Now, at this moment, Elizabeth is feeling a pride in Darcy. She rejoices that he has “been able to get the better of himself,” to rise above the prejudices of his status, class and personality.

Elizabeth’s pride in Darcy is without self-interest. She knows he is someone who is probably lost to her forever. But she is open-minded enough, she is humble enough, she is truthful enough to recognize all of the personal prejudices that Darcy has overcome to do her family a good turn.

At this point, Elizabeth and Darcy have each moved away from their prejudices and toward seeing the world and the people in it with clearer vision and understanding. They’ve moved away from ignorance toward truth.

And, in the process, in the half-blind ways of love, they have moved toward each other.

Truth and illusion

There are many ways to read and interpret Pride and Prejudice. It’s a delightfully comic story with richly drawn characters, and it’s a thrillingly convoluted love story. In addition, the novel provides a fascinating view into the role of women and men in early 19th century England through the perceptive and unblinking eye of Austen.

My reading of the novel leads me to see it as a story of truth and illusion — another way of saying pride and prejudice.

Elizabeth, at times, gets hoodwinked by illusion in one of its various forms. The deceit of Wickham in his story about Darcy takes her in because, well, Wickham is handsome and playful and seems to think her attractive. Throughout the novel, though, when push comes to shove, she opts for truth rather than illusion — though truth is often much more painful to swallow. An example of this is when she reads Darcy’s letter and, later, when she reads her aunt’s letter.

Lydia is the opposite, always choosing illusion, never looking at what is real. She could be called an airhead in modern parlance, but that implies that she’s just plain stupid.

I don’t see her that way. I see her as someone who — like her mother — consciously chooses to ignore reality and to live instead in a fantasy world. In doing so, she places herself at the mercy of those around her. She becomes someone whom others have to take care of — or, as Wickham does, to use.

Lydia chooses a life of hiding out in make-believe. She chooses a thin existence comprised of images floating in her head rather than the things and people of real life.

Choosing real life

Elizabeth chooses real life. So does Darcy. Even before eventually finding each other in love, they make choices that move deeper and deeper into the truth of existence. It is a painful road that they are on, but they walk it.

Elizabeth has pride in the strength of her character and in her willingness, even eagerness to know truth. She has pride in being a full participant in the world. Darcy, it turns out, has within himself the same pride.

They embrace this open-eyed pride rather than the close-eyed pride of prejudice and illusion. They take pleasure in being themselves — their real selves, not illusions — in the real world. That, to my mind, is why this novel is so rich and has been read and enjoyed so much over the last 208 years.

Through Elizabeth and Darcy, readers are inside a real world with two real people. Through them, readers share a vibrantly rich existence — and are shown the way of doing so in their own lives.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.8.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.