If you’re at all familiar with DePaul University’s Lincoln Park campus, you’ve almost certainly been impressed by the nine-foot-tall statue of Msgr. Jack Egan at the eastern entrance of the Student Center at Belden and Sheffield Avenues.

The statue, unveiled in 2004, is nearly double life-size. Egan was not a tall man, and he did not have the huge hands that the statue has. Those hands and the height of the artwork are evocations, however, of the strength of Egan’s commitment to social justice and his charisma in his work for those on the margins of society.

Sculpted in clay by artist Margot McMahon and then cast in bronze, it has a double-barreled title: “A 20th Century Priest: What are you doing for justice?”

The arresting work is a monument to the man who was a friend and an inspiration to mayors and the homeless and every other person he met — and a crusader whom McMahon calls a mentor.

Perhaps her greatest mentor was another fan of Egan’s, her father Franklin McMahon.

“Monsignor Egan’s consistent advocacy travels for the Civil Rights Movement, for fair housing, opposing segregation and racism was often accompanied by Dad, who drew the historic moments….He drew Monsignor Egan, ‘the city’s [Chicago’s] conscience,’ when they traveled to Johannesburg with other activist priests to tell what they had learned from the United States Civil Rights Movement.”

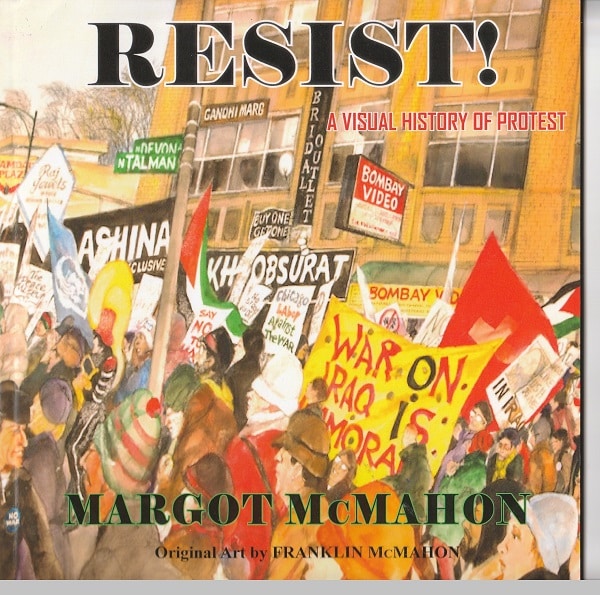

That’s a quote from her book Resist! A Visual History of Protest, an account of her father’s work for social justice throughout a long career as what one expert called “the last of the great illustrator-reporters.”

A monument to her father, an artist-reporter

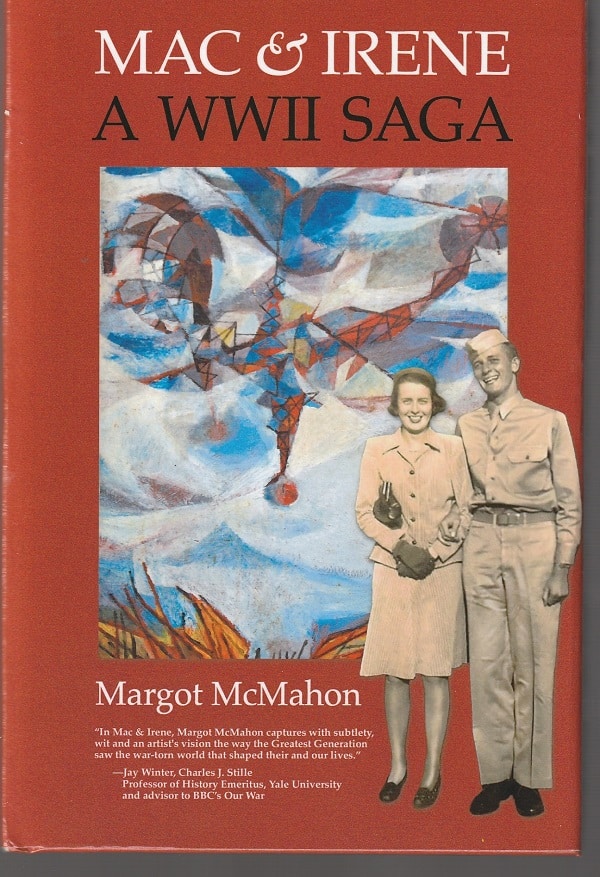

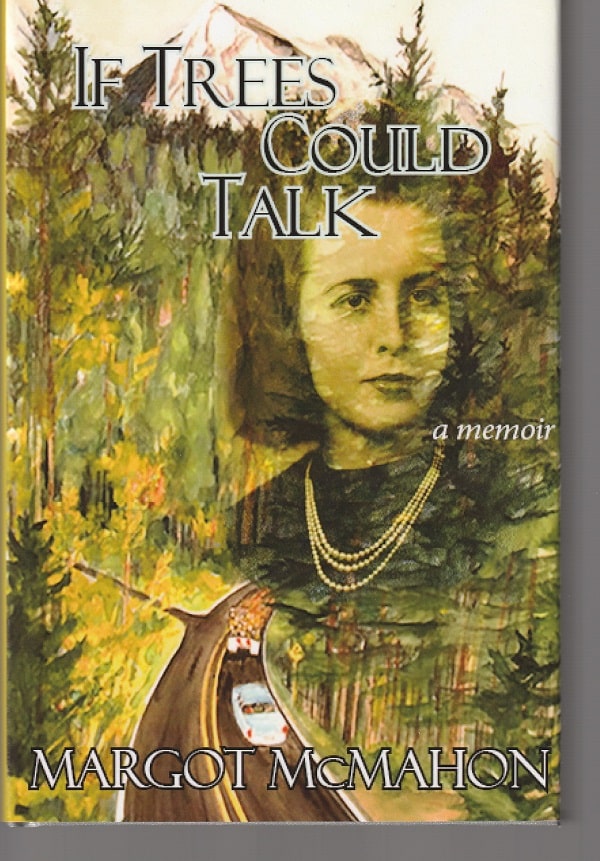

Available since December, Resist! is one of three books that McMahon has published in the last year and a half. The others are Mac & Irene: A World War II Saga about the courtship of her parents and If Trees Could Talk, a memoir. McMahon, who writes with a mix of facts and imagined scenes, uses her father’s art work through all of the books, especially in Resist!.

Together these three books are a kind of monument to her father as an important artist in 20th century America and as someone who was a major influence on her life as a sculptor and as a person.

If you lived in America in the second half of the twentieth century, you couldn’t help but come across the vibrant, colorful illustrations by Chicagoan Franklin McMahon, a much sought-after artist-reporter.

Indeed, when McMahon died at the age of 90 in 2012, the New York Times described him as the man “Who Drew the News,” noting that, despite journalism’s heavy use of photography, he built “a renowned career of drawing historic scenes in elegant, emphatic lines.”

One-of-a-kind career

Among the news events he covered were:

- The 1955 trial of the men accused of the brutal, racially motivated murder of black Chicagoan Emmett Till in Mississippi.

- The NASA space launches.

- The Chicago 8 (later Chicago 7) conspiracy trial after the 1968 Democratic Convention .

- The 1959 American League champion Chicago White Sox.

- The Kennedy-Nixon debates in 1960.

- The Second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church in the 1960s.

- Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1965 March from Selma to Montgomery.

- The 1968 riots in Chicago after King’s assassination.

- The 1973 Watergate hearings.

- The 1995 Million Man March.

Beyond recording such news stories, McMahon carried out illustration assignments from a wide range of magazines, including Sports Illustrated and the Chicago-based U.S. Catholic, and for a variety of corporations and businesses, such as International Harvester and McDonald’s Corporation. In fact, in the 1970s, he designed a set of Chicago-themed decorative plates that Continental National Bank gave out as premiums and are now hot collector items on eBay.

McMahon’s inviting and accessible charcoal drawings were often done on the fly and colored in afterward with acrylic watercolors, and his career was one-of-a-kind as a freelance artist who could work fast and adroitly on deadline with a distinctive style. Together, they made him an important figure in American art and journalism, particularly in Chicago.

McMahon provided illustrations for a number of books, and, in 1980, he published a little-noticed book of his art titled Chicago Impressions. But, aside from his journalism, ephemeral by nature, that’s all. And, since his death a decade ago, his name has been in danger of fading into the clouds of the past.

A retrospective is needed

The fact is that the career of Franklin McMahon deserves close examination by art historians and also, separately, by historians of journalism. And the public deserves a full-scale retrospective of his half-century of work. (A smaller exhibit of his social justice art was on display in Oak Park and then Ukrainian Village in 2018-19.)

Until such a thoroughgoing retrospective is mounted, his daughter Margot has been working overtime to produce her books and promote the story of her father. (She is the seventh of nine children born to Franklin and Irene McMahon. Another sibling, Deborah McMahon Osterholtz, the fourth of nine, published a collection of travel stories by her parents a year ago, The World Is Your Studio.)

Margot McMahon’s Mac & Irene tells the story of the courtship of her parents in Oak Park and the Far West Side Chicago neighborhood of Austin, in part based on her father’s recollections and in part on her reconstruction of events, based on other interviews, sources and her imagination.

“I may have started to have a chance with your mother during the Porgy and Bess song at a [St. Catherine of Siena High School] dance,” Mac told his daughter. By then, though, Mac was already smitten:

“It might have been my birthday at the ice cream parlor when I feel in love with her. The gang met at the Esquire for ice cream after school. I had just locked up my [illustrator] job at [the Catholic] Extension Magazine and was feeling pretty good. Irene and Charlotte stopped in from the Madison Street bus.”

If Trees Could Talk is the story of Margot McMahon’s life, but woven through her narrative is the constant presence, example and encouragement of her father. They weren’t just father and daughter, but also artist and artist.

As a kindergartener, she wandered into his studio in the family’s North Shore home on a Saturday, and, many decades later, she recalled the scene that she took in with an artist’s eye:

He was painting with encaustics, a mixture of pigment in hot wax….Dad’s hand, with his wrist at a vertical right angle, held a long paintbrush up above a pot of hot wax…

He squeezed paint onto a palette, dripped on some oil, mixed it with a wrist holding a paintbrush horizontally. It was a pointy paintbrush and the titanium white blob now had a bit of cadmium red in it on one side, some thalo blue on another side.

“Stop examining your belly button”

Since that day, Margot McMahon has carved out a significant career of her own. Her sculptures have been collected throughout the United States, Japan and Europe and are in the permanent collections of Yale University, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the John D. MacArthur State Park, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, The National Portrait Gallery, the Chicago History Museum, The Chicago Botanic Garden and Soka Gakkai International.

Resist!, the shortest of her three books, recounts her father’s involvement in documenting politics and protest, and it features, on its cover, a striking image of a demonstration against the War in Iraq on Devon Avenue in West Rogers Park. Inside are Franklin McMahon’s drawings from the Emmet Till murder trial and the Berlin Wall, images of Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama and Pope John Paul II and Msgr. Jack Egan.

Margot McMahon’s three books are not only a monument to her father but also an assertion of her “true inheritance…[from] and artist-reporter father and writer mother.” She writes: “They were in the heat of the troubles capturing the scenes of chaotic protests for social justice: women and gay rights, freedom of speech, workers’ rights, racial equality and anti-war.”

At the end of Resist!, she quotes her father’s creed which permeated all of his work:

“Stop examining your belly button. Get out there and make a change! If you have an inkling of injustice, make a difference.”

That’s the sort of advice that changes the world.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.11.23

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 2.24.23.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.