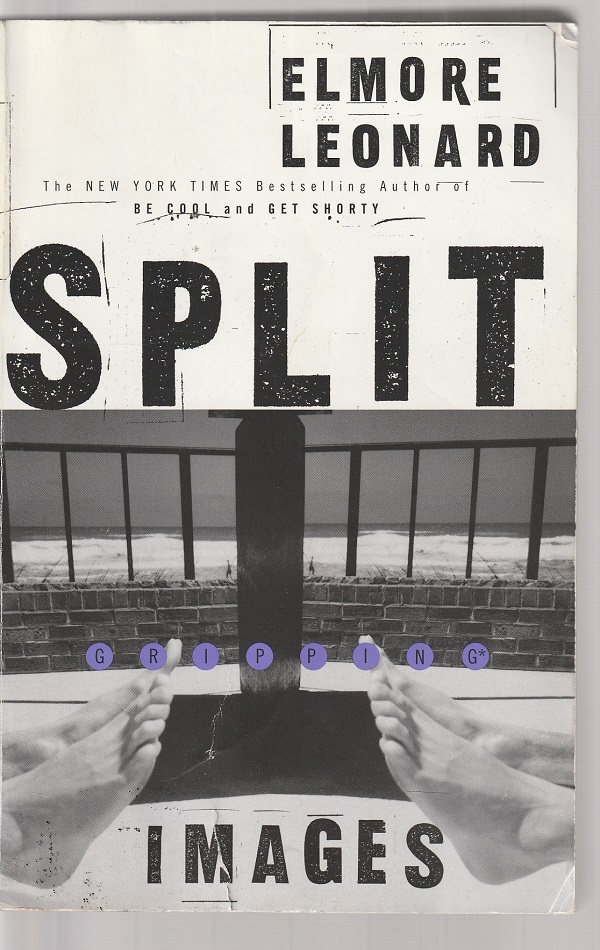

Elmore Leonard’s novel Split Images opens in this grim way:

In the winter of 1981 a multimillionaire by the name of Robinson Daniels shot a Haitian refugee who had broken into his home in Palm Beach. The Haitian had walked to the ocean from Belle Glade, fifty miles, to find work or a place to rob, to steal something he could sell. The Haitian’s name was Louverture Damien.

The bullet fired from Robbie Daniels’s Colt Python did not kill Louverture immediately. He was taken in shock to Good Samaritan where he lay in intensive care three days, a lung destroyed, plastic tubes coming out of his nose, his arms, his chest and his penis.

So much for Leonard’s usual sideways and often droll entry into his story. Here it’s just the facts, ma’am, though that, in itself, is a message to the reader.

In the next three paragraphs, the reader learns more facts — that Damien’s 50-mile trek was triggered by a stopped-up toilet in the crowded room where he paid $40 a week for a spot; that, in the hospital’s clean sheets, he looked like “a stick figure made of Cordovan leather”; and that he weighed 117 pounds and was 41 years old at the time of his death.

Robbie Daniels — the guy with movie-star looks, elegant clothes and about $100 million (about $300 million in today’s money) — was also 41.

“The top of his head”

About 50 pages later, Angela Nolan says:

“I think he’s an asshole. But I have a feeling there’s another Robbie Daniels inside the cute Robbie and that one could be pretty interesting.

“I think he likes to kill people.”

Angela is a freelance magazine writer who’s trying to do a piece on Daniels but has found it difficult to figure him out.

Except, of course, the killing thing.

Nine years earlier, Daniels was out duck-hunting with an auto firm executive, sitting in a duck blind, and, as Bryan Hurd remembers it,

“Robbie blew the top of his head off with a Browning twelve-gauge shotgun. Gold-inlaid, it must’ve cost him seven or eight thousand.”

Hurd is a homicide lieutenant in Detroit who, while testifying in court against one of Daniels’s hirelings, makes immediate and absolutely electric contact across the room with Angela who’s there for background on her Daniels article.

“ME!”

Bryan and Angela’s romance is staged by Leonard as an exquisitely slow and tentative pas de deux of deliciously delayed gratification. They’re cute kids, even though neither is a naïf. Angela is about to turn 30. Bryan is in his late 30s.

It’s one of those fictional romances that you’d love to work out in a spectacularly happy-ever-after fashion.

But, before anyone can give much thought to that, Angela has a job to do, and she continues digging for information about Daniels, still not sure what her story is going to be about. In fact, some working titles she’s listed give an indication of how unsure she is of where the piece is going:

“HI, I’M ROBBIE DANIELS”

“WHAT’S IT LIKE TO BE RICH?”

“I WAS JUST SAYING TO MY VERY GOOD FRIEND GEORGE HAMILTON THE OTHER DAY…”

“WHO WOULD I RATHER BE THAN ANYONE?…ME!”

“SPLIT IMAGES: HOW RICH-KID ROBBIE DANIELS DEFIES YOUR VIEWFINDER.”

“An animated Ken doll”

Despite the playfulness that Bryan and Angela exhibit while falling deeper in love, the grim tone of the opening paragraphs pervades the rest of Split Images.

It seems pretty clear that, when he wrote this novel, Leonard was really angry, with a real-world anger, at the wastefulness, uselessness and inanity of those rightfully called the idle rich.

Daniels is Exhibit A of that group and is probably, for all his pretty-boy beauty, the most unattractive sociopath in all of Leonard’s fiction.

That’s saying a lot since Leonard usually features at least one stone-cold killer in every novel but draws them in a way that they’re interesting human beings. Often, he puts readers into the head of such a killer, and the guy, for all his bloodthirstiness, turns out to have the same problems as any one of us — traffic jams and irritating relatives and balky door handles.

Daniels, though, as Leonard describes him, is a boringly surface personality. He’s shallow and selfish and expects things to always go his way. He’s not so much as human being as an animated Ken doll.

In other words, not someone the reader will relate to.

Only the start

Even the comic elements of Daniels and his love of guns and his jejune preoccupations and his love of playacting aren’t very humorous. I’m sure that Leonard didn’t like Daniels very much.

With its grim tone and story and its bland sociopath, Split Images is a distinctive Elmore Leonard novel.

Daniels gets what’s coming to him.

But, in his idle-rich way, he ruins many lives. And the auto executive and the Haitian are only the start.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.26.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.