Yoga is devil-worship — that’s what some American Christian leaders say, such as Mark Driscoll, an evangelical pastor who, in a 2010 sermon, told his congregation:

“Yoga is demonic. If you just sign up for a little yoga class, you’re signing up for a little demon class.”

Blame the Book of Revelation.

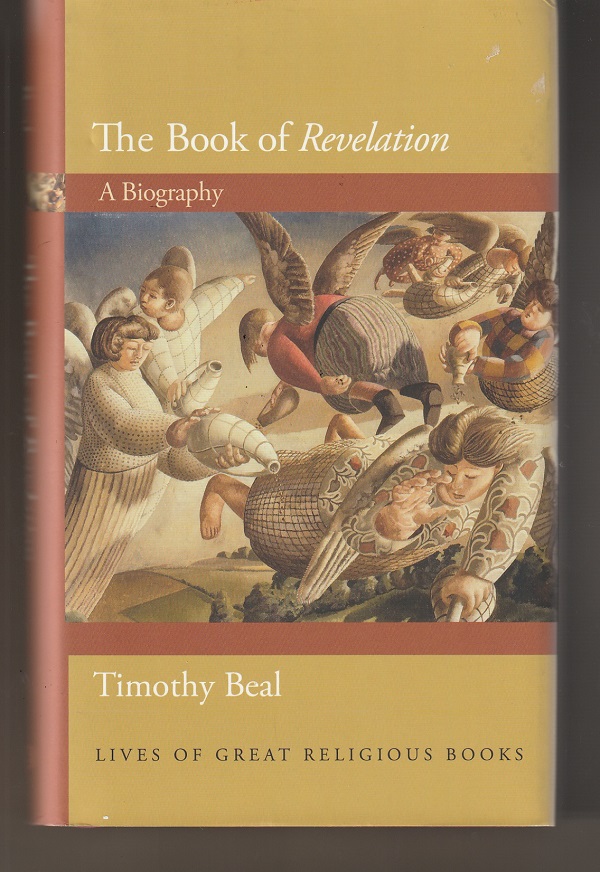

Actually, a lot of odd, bizarre and weird beliefs have their roots in that last book of the New Testament, and it’s easy to see why, as Timothy Beal explains in The Book of Revelation: A Biography, published in 2018.

The Book of Revelation, attributed to John of Patmos, totals about 12,000 words, arranged in 404 verses in 22 chapters. Early on in his own book, Beal spends eighteen pages and about 5,000 words giving an abridged overview of the twists and turns of Revelation’s visions upon visions upon visions.

It is quite a spectacle, a roaring cascade of images such these, taken at random:

- “A Lamb standing as if slaughtered, having seven horns and seven eyes.”

- Four angels leading 200 million cavalry with sulfur-breathing horses that have the heads of lions and the tails of serpents.

- The Great Whore of Babylon “with whom the kings of this earth have committed fornication.”

- The “lake that burns with fire and sulfur, which is the second death” for the “cowardly, the faithless, the polluted, the murderers, the fornicators, the sorcerers, the idolaters, and all liars.”

“A volatile mix of feelings and resonances”

Beal, a scholar of religion at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, summarizes Revelation as a “barrage of revelations, scenes of fantastic violence and brilliant extravagances, piled one  on top of another without pause or transition except ‘and I saw’ and ‘and I heard.’ ” And he writes:

on top of another without pause or transition except ‘and I saw’ and ‘and I heard.’ ” And he writes:

They are written descriptions that defy visual depiction. Time and space unfold in John’s descriptions of his visions in ways that, paradoxically, simply cannot be translated into visual images.

As such, John’s literary images simultaneously provoke and resist our capacities of reason and imagination, eliciting….a volatile mix of feelings and resonances that resist any singular interpretation or representation and instead invite readers and hearers into “impressionistic imagination.”

Doesn’t make sense

Beal calls this “generative incomprehensibility.” Revelation is, he writes, “an uncovering of things that remain hidden, a seeing of things that remain unseeable.” It’s not so much a revelation as it is a mystification.

Revelation doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t follow logic. It doesn’t fit together. And that, Beal argues, is the secret to its many wildly divergent lives over the past twenty centuries.

Since it doesn’t seem to mean anything in particular, it can said to mean almost anything.

Down the years, as a work that is, at its core, incomprehensible, Revelation has attracted thinkers and holy people who have offered a key to what it means, asserted answers to the flood of questions that it prompts. Some have even used the work as the secret to the meaning of Christianity and human existence.

Similarly, because of its chaotic opaqueness, thinkers and spiritual searchers have been able to focus on this or that scene, this or that image, in isolation from the rest of the work. Since Revelation doesn’t explain how its hundreds of images and scenes fit together, it’s easy enough to pull one out.

Who, for instance, is the Great Whore of Babylon? Revelation doesn’t say, so generations of readers have come up with their own answers — Rome? Jerusalem? The Catholic Church? More recently, the label has been slapped onto public figures such as Hillary Clinton, Angela Merkel and Michelle Obama.

Lives of Great Religious Books

The Book of Revelation: A Biography is one of twenty-four installments in the delightful Princeton University Press series called Lives of Great Religious Books.

Each of the addictively readable short works of 200 pages or so is written by an expert who, with an accessible style aimed at the general reader, examines how the book came to be and how it has impacted world culture ever since.

Among the spiritual works featured in the series are The Dead Sea Scrolls, the Book of Job, the Koran in English, the Book of Genesis, the Book of Mormon, the Talmud, the Book of Common Prayer and the Autobiography of Saint Teresa of Avila.

“Many far better books available”

Beal’s aim is to show “Revelation’s remarkable, shape-shifting, contagious vitality, for better or worse, and with no end in sight.”

In seven chapters, he looks at a variety of reactions to Revelation, such as:

- Saint Augustine and his seminal theological work The City of God.

- Two apocalyptic visionaries from the twelfth century (Hildegard of Bingen and Joachim of Fiore) with their separate and different but similarly complex decodings of Revelation.

- The African American mid-twentieth-century outsider artist James Hampton who was inspired by Revelation to create The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly, described by many as the greatest work of American folk art.

- The great Protestant reformer Martin Luther and his chief propagandist, artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Luther was not a fan, saying of Revelation that he considered it “neither apostolic nor prophetic.” No one can say what Revelation means, and that’s “the same as if we did not have the book at all.” Besides, he added, there are “many far better books available for us.”

Nonetheless, Luther included Revelation in his groundbreaking translation of the Bible into German, and that’s where Cranach comes in. Borrowing from the work of Albert Durer, Cranach provided dozens of illustrations of scenes in Revelation that were included in the Luther Bible and helped boost its popularity — and have colored our images of Revelations and its many visions.

“Monstocizing religious otherness”

One of the most disturbing reactions to Revelation has been the tendency of Christians, particularly evangelicals, to equate the devil monster of Revelation with other religions. Upset at the rise of religious diversity, some Christian leaders have engaged in this sort of “monster-making,” decrying “non-Christian religions, especially Buddhism and Hinduism, as monstrously other forms of devil worship.”

And that’s how yoga has come under fire as devil worship. Beal quotes one self-proclaimed witch-turned-Christian as stating:

“Once you bring these practices into your life, you are also inviting these demonic entities into your home and your family.”

Such talk, he writes, is “part of a shared genealogy of monstrocizing religious otherness that traces itself back to Revelation, the monster-maker’s Bible.”

Revelation is “an othering machine. With it between me and the world, difference, especially religious difference, translates into diabolical otherness — anti-me, anti-us, anti-God.”

This is the dark side of “Revelation’s remarkable, shape-shifting, contagious vitality.”

Incomprehensibility can be simply confusing. But, when put in the service of fear and hate, it can be deeply destructive.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.17.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.