The Cave at Altamira, published in 1998 by Harry N. Abrams, is a celebration by scholars from several fields of the artistic wonders of a meandering cave near the small town of Santillana del Mar along the farthest northern edge of Spain, not far from the Cantabrian Sea.

The town is very old, tracing its roots back to a monastery founded in 870 AD. But it can’t hold a candle to the cave, discovered a century and a half ago.

Through carbon-dating and other scientific wonders, experts are able to determine that humans first occupied the cave about 18,500 years ago.

The art in the cave was executed, the best they can determine, about 14,400 years ago, and it was saved because of a landslide that closed the entrance about 13,000 years ago.

Those many tens of thousands of years are difficult for a modern person to understand.

I live in Chicago, a city that’s only about 200 years old. I live on a continent that was populated by various indigenous peoples but unknown to the rest of the world until the late fifteenth century. Rome’s empire rose 2,000 years ago and lasted only four centuries. Prior to that, the Egyptian dynasties had ruled for about 3,000 years.

When Egypt first rose, the paintings in the cave at Altamira were already nearly 10,000 years old.

And what paintings!

“The most magnificent art ever”

The scholars who have contributed essays to The Cave at Altamira are rapturous about the cave, found in 1879, particularly the paintings of the Great Panel on the ceiling of the largest section, called the Polychrome Chamber.

Antonio Beltran, the book’s editor, notes that, since 1906, the cave has been called the Sistine Chapel of ancient art, and adds that Pablo Picasso said, “Not one of us could paint like that.”

Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, an important expert on the art of prehistoric art who died in 2010, writes that the works of art in the Polychrome Chamber make it simply “one of the great monuments of all time.” And Pedro A. Saura Ramos, an expert in the photography of prehistoric sites who was married to Muzquiz, goes even further.

Saura, who has been taking photographs of the cave since he was first shown it in 1969 and whose images form the core of The Cave at Altamira, writes:

When I first contemplated that ceiling, full of life, expression, color, and magic, I was overcome by its grandeur. Though I risk making an almost sacrilegious statement in saying this, I shall always believe that the vault of the Polychrome Chamber at Altamira is the most magnificent art ever produced by humankind.

“The work of one creator”

Most of the photos in the book and much of the discussion have to do with the Great Panel which, from everything that can be determined, was painted by a single artist.

The book goes into great detail about the methods that scholars believe this artist used to create the thirty large images of bison and other animals on the ceiling. Indeed, Muzquiz oversaw the attempts to replicate the methods of the ceiling painting through trial and error in a similar though undecorated cave nearby. The result was substantive theories about the artist’s approach to the work.

“The Great Panel at Altamira is essentially the work of one creator, the one responsible for the large polychromes,” she writes, adding that the artist wasn’t only gifted as a painter but also a sculptor.

That’s because the figures weren’t just painted onto the ceiling but were constructed using the cracks in the ceiling stone as well as the projections of the rock.

One artwork, two views

For instance, look at this image of a bison bowing forward and looking back, made with charcoal and red ocher, and echoing the anatomy and movement of a living creature — a stunning work of art.

But, as Ramos and other essayists note in the book, this flat image only captures part of the wonder and beauty that the artist created more than fourteen millenniums ago. Consider this image that Ramos made using lighting from an acute angle to highlight the surface of the rock.

By looking at the two images, a reader of The Cave at Altamira can get an approximation of what it would be like to see the three-dimensional art in person.

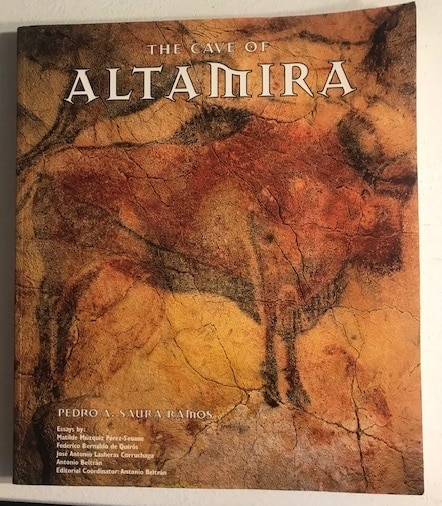

Another example is the bison on the cover. In creating this image, the artist built the top of the bison’s head using a somewhat horizontal ceiling crack.

“A deeply thought-out work”

Such images — the book is filled with such images — say much not only about the artist but about the artist’s community. Muzquiz notes that the community that used the cave allowed the artist to devote long periods of time to the works.

During this time devoted to the works, the artist “created several figures of a playful character, making use of a number of techniques to create a unity, applying a complex combination of procedures with the use of simple materials — burins, charcoal, iron oxides, and water — following a prescribed order in the application of [the] processes.”

It was, she writes, “a deeply thought-out work, in terms of both its conception and practical solutions.” She goes on:

The strokes are confident and made [without] having to be erased or reworked. While all the bison differ from each other, they share similar proportions and are of a similar size. The painter must have stared long into the eyes of the bison….to capture the intensity of the animal’s gaze. Today, they look back at us with equal intensity.

The bison seem to have weight, and to be breathing. The fact that each of their tails has been painted in a different position reminds us, as we look from one to another, of the constant motion of the tails of real bison.

In the erudition of its essays and the wonder and creativity of its photographs, The Cave at Altamira is a beautiful, striking and moving homage to the people of the cave and to their artist.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.14.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.