Meister Frantz Schmidt executed 394 people during the course of a nearly half century as an executioner, mostly in the important German city of Nuremburg. In addition, he tortured, flogged and disfigured hundreds more in punishments ordered by the city administration.

Those administrators were representative of civic leadership in that early modern era. They saw such malefactors as symptoms of deep social problems, and they employed gruesome public punishments — often for non-violent, seemingly minor infractions — as a very direct form of crime-fighting.

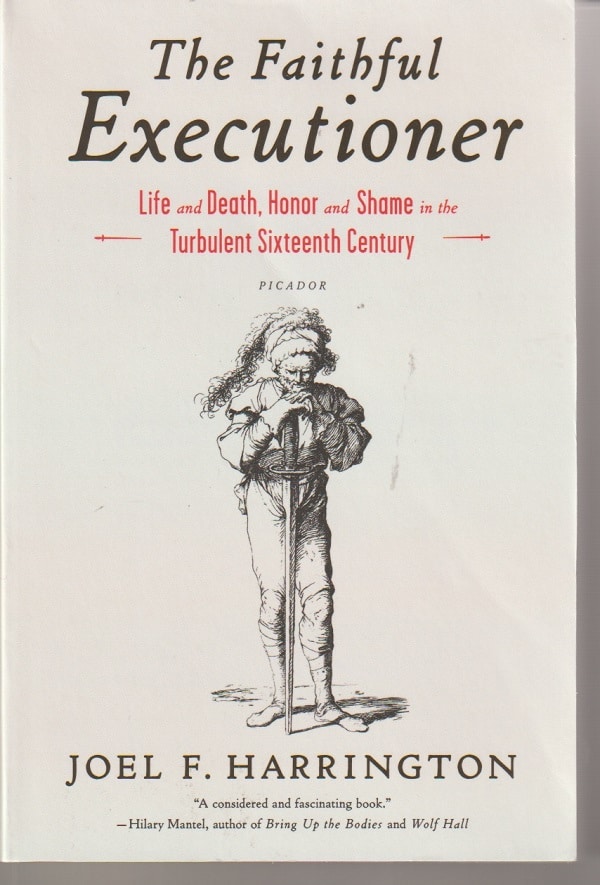

Schmidt, though, had a more direct and subtle understanding, as historian Joel F. Harrington details in his 2013 book The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth Century.

Thieves and other nonviolent offenders indisputably deserved punishment in Meister Frantz’s moral universe, but[, as he saw it,] their crimes, like those of prostitutes and pimps, usually represented the conscious lifestyle choices of weak, rather than malicious, individuals….

Despite the executioner’s exceptional attunement to the losses suffered by their victims, his primary emotional response to the 172 thieves he hanged during his career was less anger than weary resignation. Their own selfish choices had brought them to this moment, and Schmidt never once excused the circumstances behind their thefts.

“Head-shaking sadness”

Schmidt, a man who started life at the bottom of his society’s ladder, had no sympathy for those who turned to crime, no matter how petty, writes Harrington. But they left him with “head-shaking sadness.”

And the author notes that, looking back 400 years, our world, from the context of its own beliefs and values, would be likely to ask:

“How could a society hang a man for stealing honey?”

Schmidt’s question, he writes, would have been different:

“Why does a man repeatedly risk hanging to steal some honey?”

“Assumptions and sensibilities”

There is a small subgenre of books about the history of executioners, and these tend to emphasize the more macabre and grisly aspects of the job. That’s not Harrington’s goal in The Faithful Executioner.

He’s a social historian, and he uses the life and career of Schmidt to examine the role that public executions played in 16th century Europe in the effort to bring about civic order. And, throughout his book, there is a dialogue, sometimes overt, sometimes implicit, between the beliefs of that era and those of ours. Harrington writes that his account is about Schmidt but also about a variety of questions, such as:

Which assumptions and sensibilities made the judicial violence that Meister Frantz regularly administered — torture and public execution — acceptable to him and his contemporaries yet repugnant to us in our own times? How and why do such mental and social structures take hold, and how do they change?…

The story of Meister Frantz of Nuremberg is in many ways a captivating tale from a faraway era, but it is also a story for our time and our world.

A good name

Harrington is right: Schmidt’s story is captivating, and much of that is due to the author’s painstaking research and keen insight.

Many executioners of that era and later kept a journal, and Schmidt’s contains 621 entries in chronological order, in the form of two lists: the first, listing capital punishments carried out from 1573 to 1617, and the second, the corporeal punishments from 1578 to 1671, i.e., “floggings, brandings, and the chopping of fingers, ears, and tongues.”

Initially, Harrington found the journal — published often over the centuries — to be fascinating in its descriptions of criminals but frustrating in the way Schmidt seemed to hide in the background.

Then, he discovered an older manuscript copy of the journal that made it clear that later versions were garbled by myriad emendations, mistakes and revisions. It also showed that Schmidt began the journal at the request of his father.

That fact was of prime importance as Harrington learned when he came across a document in the Austrian State Archives in Vienna in which the 70-year-old Schmidt, now retired, asked Emperor Ferdinand II to restore his family’s good name — lost, through no fault of the family, in 1553.

“Bring infamy”

Schmidt’s father Heinrich was a respectable woodsman and fowler in the town of Hof. This was a town that was ruled, very badly, by Lord Albrecht Alcibiades. On October 16, 1553, the well-hated Albrecht ordered the execution of three gunsmiths for an alleged plot on his life.

Hof was too small to have a full-time executioner, and the normal procedure was to send for one from a nearby city. Instead, “the headstrong margrave invoked an ancient custom and commanded a bystander to carry out the deed on the spot” — Heinrich Schmidt.

The hapless woodsman protested that this “would bring infamy to him and his descendants.” The profession of executioner was, in this society, a “dishonorable” occupation that would keep Heinrich and his family isolated from “respectable” citizens.

Deaf to the protests, Albrecht threatened to have Heinrich executed if he failed to carry out the job.

And, so, the Schmidt family had ever since lived under this curse. Heinrich was now a professional executioner, and his son Frantz, born the next year and blocked from most other careers, followed in his footsteps.

“God’s hand”

The Faithful Executioner is the story of Frantz’s faithful, lifelong — and ultimately successful — quest to lift this “infamy” from his family. And, of course, it is about the job he carried out.

Harrington does much to fit the act of execution into the context of this era’s morality, fears, physical setting (i.e., a totally dark night), goals and religion. This was a time before long-incarceration and before police departments. Civic leaders had relatively few strategies for crime-fighting. Execution was a key one.

Indeed, Martin Luther preached, “If there were no criminals, there would also be no executioners.” And he went on:

“The hand that wields the sword and strangles is thus no longer man’s hand but God’s hand, and not the man but God hangs, breaks on the wheel, beheads, strangles, and makes war.”

“Known and admired”

Although, in the 16th century, executioners were getting more professional and orderly, they were still judged by the company they kept or, at least, had to work with: “godless and rash people,” according to one legal scholar of the time, such as:

“sorcerers, robbers, murders, thieves, adulterers, whoremongers, blasphemers, gamblers, and others burdened with coarse sins, scandals and troubles.”

So, the strategy of Frantz Schmidt was to avoid them whenever possible.

He stayed away from taverns with their rambunctious crowds of young men. He stayed away from loose women. He developed a reputation as a sober, quiet, reliable man. “The self-isolation must have been emotionally difficult for Frantz,” Harrington writes, but it was carried out Schmidt’s lifelong goal in mind of making himself a “respectable” citizen:

Thus, Frantz did not make a great social sacrifice when he came to what was a remarkable decision for a man of his era: never to drink wine, beer, or alcohol of any kind. It was a vow he apparently kept for the rest of his life and for which he eventually became widely known and admired.

The sacred goal

In fact, Harrington might have called his book The Admired Executioner, a seeming oxymoron in Schmidt’s era.

Yet, as a title, The Faithful Executioner is better.

It was through Schmidt’s faith in his own ability and self-possession, over the course of five decades, that brought for him and his family the sacred goal he had sought: freedom from the calamity of being an executioner.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.8.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.