Over the past 76 years, the Playtex brand of bras, girdles and other women’s products hasn’t been shy when it comes to advertising its merchandise.

In fact, in 1949, it published an ad in Life Magazine showing four stop-action images of a model, dressed only in a Playtex bra and “Living Girdle,” executing a short ballet leap. But the leap was nothing compared to a small step that a man took two decades later.

That step was by U.S. astronaut Neil Armstrong just before 11 pm (Eastern Daylight Time) on July 20, 1969, when he came off the ladder of NASA’s lunar module to become the first human to set foot on the moon and said, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Armstrong was wearing a space suit that had been manufactured for NASA by Playtex.

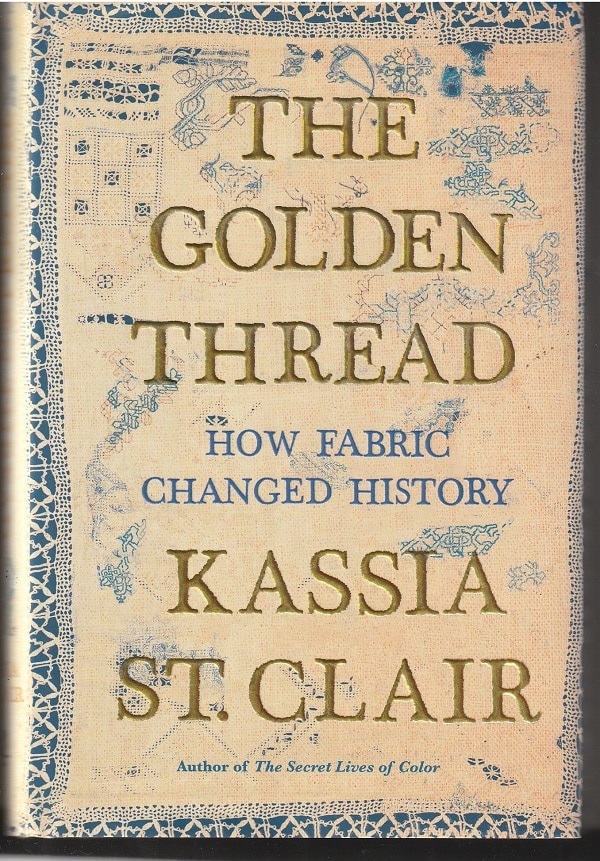

How Armstrong came to be wearing a Playtex space suit is one of the many fascinating stories that Kassia St. Clair tells in her delightfully revelatory, engagingly written 2018 book The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History. In a preface, St. Clair states:

Fabrics — man-made and natural — have changed, defined, advanced, and shaped the world we live in…. For much of recorded history, the four principal sources of natural fibers — cotton, silk, linen, and wool — have borne much of the strain of human ingenuity. They have been pressed into service to give warmth and protection, demarcate status, confer personal decoration and identity, and provide an outlet for creative talent and ingenuity.

More recently, synthetics have been brought into the game — literally, as St. Clair details in a chapter on the impact that human-created sports fabrics have had on the performance and records of athletes.

Wearing lace to the scaffold

St. Clair’s book, as she notes early on, isn’t meant to be an exhaustive survey of all the ways that humans have interacted with textiles. Instead, she offers “thirteen very different stories that help illustrate the vastness of their significance.”

The Golden Thread, for instance, uses Vermeer’s painting The Lacemaker as a jumping-off point to look at the elegance and meanings attached to lace as well as the 16th century craze for ruffs, those thick lace neck adornments that give the impression of choking the wearer in beauty.

In this chapter, St. Clair’s reader learns that needlework was an occupation that women of all classes were encouraged to develop, such as two of the most powerful people of the era: Catherine de’ Medici and Mary Queen of Scots.

Indeed, when Mary crossed her cousin Elizabeth I — another lover of lace — one too many times, she “went to the scaffold in 1579 wearing white linen bobbin lace.” She wasn’t the only figure of that era, male and female, who went to their execution in lace finery.

So sensitive to the nuances of lace were wealthy people of that time, writes St. Clair, that the artist Diego Velazquez got into a dispute with a young noblewoman of Zaragoza.

She refused to accept the finished portrait because, she said, the artist had failed to properly depict the quality of the lace — “puntas de Flandes muy finas” — of her collar.

One million square miles of sailcloth

The paintings of Velazquez and Vermeer are indications that fabrics aren’t only for wearing. They are, as the young noblewoman’s complaint indicates, signposts of status. And they are an economic engine as the woman in yellow making lace shows.

Fabrics are also for transportation. Consider sails.

Their function is to harness the wind to drive a craft over water. But from such a simple premise, a million possibilities bloom. Indeed, the flock of historical sails is so densely populated it requires an entire language to describe it. They come in myriad sizes and shapes — claw, square, and lateen — some of which are unique to a particular class of ship, such as the traditional Indonesian pinisi or the latest monohull racing Moth.

St. Clair devotes a chapter to sails, “Surf Dragons,” focusing in particular on the woolen sails of the Viking ships that marauded along the coastlines of Europe over a three-hundred-year period ending around 1100 A.D. Sails were a technological innovation that the Norsemen embraced wholeheartedly.

This was natural enough: sails dramatically expanded their horizons, allowing them to travel farther, with larger loads, and giving them a crucial edge against their rivals. By the time of King Canute’s North Sea Empire during the first half of the eleventh century, the fleet — encompassing everything from the grandest warship to the humblest fishing vessel — would have required around one million square miles of sailcloth. The majority of this would have been made from wool.

To produce that much wool required millions of sheep, and that required land for those sheep to graze. St. Clair notes that, as the fleet grew, the Viking needed to find more land, and that had fueled the need to marauder.

Indeed, some textile historians argue that “the spiraling need for land, sheep, and wool” was, at least in part, “responsible for their aggressive expansion into new lands such as Normandy, Greenland, and, indeed, America.”

“Exchanged for cotton cloth”

The deeply intricate connection between cotton and the enslavement of Black people in the American South is the subject of St. Clair’s most disturbing chapter. Here, fabric and the raw material of fabric was also the raw material of racism.

In fact, as St. Clair details, enslaved Blacks weren’t only used to produce cotton, but were enslaved with cotton:

While it is often assumed that the currencies used to buy slaves were weapons or precious metals, a great many more were exchanged for cotton cloth…

At first the cloth was bought from India; later, raw cotton was imported to Europe where it was woven with designs tailored for the African market. This was big business.

“An imposed uniform [of] the dreariest and cheapest fabrics”

In the South, there was such a thing as “Negro cloth,” the cheapest and most inferior fabric. The most frequently mentioned type was homespun, often made by the slaves themselves, “a plain weave of either wool or cotton,” depending on what was inexpensive and near at hand.

The result, writes St. Clair, was a dehumanization of the enslaved person, required to wear “an imposed uniform made from the dreariest and cheapest fabrics available.” Indeed, clothing was yet another way in which the dynamics of power were played out between the enslavers and the enslaved.

Rough and coarse rather than smooth; loose rather than fitted; dingy rather than brightly colored; scratchy rather than soft; lusterless rather than sheened, slave clothing as procured and defined by whites visually demarcated their low status.

At least, that was the intention. In practice, slaves not only proved eminently capable of obtaining clothing theoretically forbidden to them, but also of carefully and intentionally carving out an aesthetic altogether their own.

“More akin to making girdles”

The “imposed uniform” of enslaved people in the South is one of hundreds of examples of information, insight, fact and anecdote that will surprise and enlighten any reader of The Golden Thread.

St. Clair notes that, when she studied history in college, other professors and students disdained fabrics, seeing clothing as “frivolous and unworthy of notice, despite its evident importance to the society under discussion.” In her book, she offers an in-depth look at some of the many ways that fabric has “changed, defined, advanced, and shaped” history.

Such as that Playtex space suit. Officially, it was known as A7-L — “A” for Apollo, “7” because it was the seventh in the series, and “L” for ILC, the parent company of Playtex.

Despite NASA’s objections, the making of [A7-L]…was much more akin to making girdles than anyone at the space agency would have cared to admit.

Each suit was fashioned by hand by seamstresses, pattern-cutters and makers, all women, using Singer sewing machines and employing “skills both inherent and honed from years of making women’s underwear.”

Design solutions used in the suit were adapted from a variety of techniques, including the making of diapers and “the same sheer fabric used to make many Playtex bras.” In addition, each suit had “a layer of fluffy girdle-liner after complaints were made about the discomfort caused by rubber chafing against the skin.”

“Hunched over their glue pots”

Michael Collins, the member of the Apollo 7 team who remained on the spacecraft during the visit of Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin to the surface of the moon, was the astronaut who had worked with the design and production of the space suits.

St. Clair quotes a couple sentences from Collins’s 1974 autobiography Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys in which he gives credit to those many women who fashioned the space suits while also being careful not to mention Playtex by name and while using jocular terms that aren’t as acceptable today.

When you think of a space walker, you may visualize a chap confidently exploiting the most advanced technology that this rich and powerful nation can provide, but not me, friends.

I see a covey of little old ladies hunched over their glue pots in Worcester, Mass., and I only hope that between discussions of Friday-night bingo and the new monsignor, their attention doesn’t wander too far.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.26.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.