Saint Teresa of Avila was a woman of 16th century Spain, a nun mystic experienced in the bliss and pain of religious ecstasy but also nun living under the power of male clergy and hierarchy who were wont to mistrust women and mysticism.

One of the many striking aspects of her life is that she protected herself and the intimate connection that she had developed with God — which she described as “nothing else than a friendly relationship, a frequent private conversation with Him by whom we know ourselves to be loved” — by writing her autobiography, La Vida de la Santa Madre Teresa de Jesús (The Life of Teresa de Jesus), one of the great religious books of human history.

It is a work that explained, as best she could, the inexplicable ecstasy of Teresa’s communion with the Deity while also explaining it in a way that did not lead her into theological territory that could have resulted in her being silenced or even burned at the stake. Writes Carlos Eire in his well-crafted, clear-eyed examination of the autobiography’s life over the past five centuries:

At its deepest spiritual level, it is all about the intermingling of heaven and earth, and about the highest levels of divinization attainable by humans. At its most mundane, it is a remarkable woman’s account of her life in golden age Spain.

“Transcend the sensory material world”

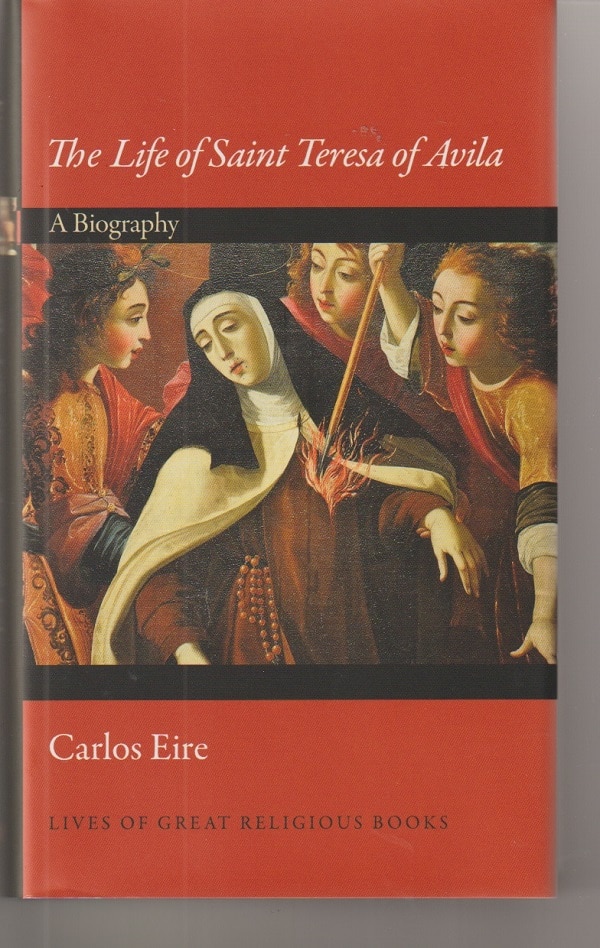

Eire’s book The Life of Saint Teresa of Avila: A Biography was published in 2019 by Princeton University Press as an installment in its extraordinarily rich series Lives of Great Religious Books.

Each work, written for the general public by an expert, looks at what the great religious book is and says and at how it has had an impact not only within its religious tradition but throughout the secular world down the centuries. Among the works already covered are The Book of Common Prayer, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Koran in English, the Talmud, C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, the Book of Exodus and The Jewish War by Josephus.

Like the other Princeton installments, Eire’s book is sprightly in its examination and explanation of how Teresa’s Vida came to be written and how her words attempt to capture the ineffable. Consider this opening paragraph for his chapter on the mysticism in the work:

Teresa’s Vida is a mystical treatise full of claims that many readers in our day and age would consider bizarre, insane, or fraudulent. Its central premise is as outrageous as all the raptures and transports described within it; after all, this is a text that assumes — unquestionably — that human beings can transcend the sensory material world and have intimate relations with the Creator of the universe. And it is precisely this seemingly preposterous aspect of the Vida that begs for attention, for to deal with it fully is to plumb what gives it structure and meaning.

Believed deeply

With that paragraph, Eire challenges his reader. Essentially, he is saying:

If you are going to read my book, you are going to have to acknowledge that, although the present secular age would consider Teresa a crazy woman or a scam artist, she believed deeply in what she was writing.

If you are going to read my book, you are going to have to acknowledge that, although the present secular age would consider Teresa a crazy woman or a scam artist, she believed deeply in what she was writing.

A woman of her time, she had no doubt — no doubt — that communication between human beings and God was not only possible but the fullest attainment of a human life. She had no doubt that she had experienced the highest form of this communication in the form of ecstatic raptures and physical manifestations, such as visions and even levitations. (Teresa found that levitations, which could be seen by those around her, were a distraction, she writes, and she asked Jesus to stop them which He did.)

While present-day people immersed in a deeply materialistic culture may find it difficult or even impossible to relate to Teresa’s experiences, the physical and spiritual ecstasy (and pain) was, for her, a journey to the deepest part of her faith and her existence.

To the modern reader, Eire is saying:

While this may seem preposterous to you, there is no way you will understand why this autobiography had such an impact on its age and ever since unless you are willing to listen to what Teresa has to say for herself and about her raptures.

“Intimate moments with God”

Most people write their autobiographies to have their say and often out of ego. Teresa, however, didn’t seek to write hers. She was ordered to do so by church authorities so that they could use her writing to decide whether she was an orthodox Catholic or misguided or perhaps a heretic.

As a result, the Vida is many things: a defense of her life and beliefs, a narrative of Teresa’s encounters with God, an autobiographical exposition of mystical theology and something of an instruction manual. Eire writes:

The Vida is full of accounts of Teresa’s otherworldly phenomenon: visions, locutions, trances, ecstasies, levitations, encounters with angels and demons, glimpses of heaven and hell, and intimate moments with God himself.

Vida is a journey to another dimension, a gripping narrative as full of marvels as Homer’s Odyssey, which also happens to be about an exile straining to go home.

“Into God’s arms”

Spain is a dry, arid land, and the central metaphor in the Vida — the metaphor for the journey to reach full communication with God — has to do with keeping a garden watered in such a landscape. Teresa provides four steps.

The first step, comparable to drawing water from a well one bucket at a time, involves actively meditating and praying aloud.

The second, akin to using a waterwheel and an aqueduct, is less active, more moving toward the experience of what she and others call the prayer of quiet.

The third, which is like irrigation using a running stream, requires no active effort. Instead, God “assumes the work of the gardener and lets the soul relax.” The soul, for her part, “flings itself totally into God’s arms.” Teresa writes that this sort of prayer is “a union of the whole soul with God.”

The fourth is that of falling rain. Teresa writes:

“In this state of prayer, there is no feeling, but only enjoying, without any comprehension of what is being enjoyed.”

This is a prayer of union.

“It is obvious what union is. It is two distinct things becoming one.”

“Audacious, unrestrained optimism”

In the first two hundred years after Teresa’s death, the Vida was a staunch, very Spanish statement of Catholic belief in the face of Protestant rejection and ridicule.

In the last century or so, the autobiography has been attractive to a great and extremely diverse audience of what Eire calls “strange bedfellow,” from modern saints to modern dictators, from fascists to feminists, “many of whom despise one another, or at least would feel uncomfortable if asked to gather for tea in the same room — even in a very, very large room.”

The saints are easy enough to understand although the lives of three of the most prominent were very different from Teresa’s:

- St. Therese of Lisieux, the Little Flower, known for “the little way,” a French nun, cloistered like Teresa but not the powerhouse intellectual active in the world as she was.

- St. Edith Stein, the German-Jewish philosopher, compared favorably with Martin Heidegger, who became a Catholic and a nun and died in the Holocaust at Auschwitz.

- Dorothy Day, the American journalist and social activist, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, an unwed mother who famously refused to be called a saint, whose life was devoted to crusading on behalf of the poor and dispossessed.

“Sipping hot chocolate”

Also easy to understand in this present age and present stage of the Women’s Movement is how Teresa has become a feminist exemplar.

Yet, in a more problematic reading of her life, there are some feminists who have labeled Teresa a “queer icon” who found a non-binary path through a phallocentric world — a label, Eire writes, “that would have left Teresa in apoplectic shock or prompted her to greater austerities and ascetic extremes than the ones she inflicted on herself to atone for the apostasy of all Lutherans.”

Even stranger, perhaps, is the decision of Generalisimo Francisco Franco and his Fascist troops to adopt Teresa as their patron during the brutal Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. This sort of misuse of a saint from the past isn’t unusual. The French have often sought to bolster their military adventures by invoking St. Joan of Arc.

Joan was burned at the stake by English soldiers and their French allies, so she left no physical relics. Teresa, however, was exhumed several times, and her uncorrupted body was cut up into various pieces as holy mementos. And, though circuitous circumstances, one of those, her left hand, ended up in Franco’s possession. Eire writes:

A visitor to Franco’s office was once surprised to find him signing death sentences while seated at his desk, sipping hot chocolate, with Teresa’s hand next to him near his elbow.

“Audacious, unrestrained optimism”

For much of the last century and a half, generations of psychiatrists and others have dismissing Teresa’s raptures as hallucinations or part of a fraud scheme. She’s been described as hysterical, a nymphomaniac, a “typical shrew,” mentally ill and an epileptic.

They speak with the voice of science, of hard, cold facts. Teresa spoke and continues to speak through her Vida with the voice of faith.

And she is someone that more and more people today are turning to. That shouldn’t surprise anyone. After all, the core message of Teresa’s book is one of extravagant hope, as Eire explains:

When all is said and done, however, it is not just the Vida’s how-to approach to prayer and to developing a life of the spirit, or its engrossing narrative, or its feminine perspective that have made it one of the world’s great religious books.

It could be argued that above all, it is really its audacious, unrestrained optimism about the human potential for love and divinization, and its affirmation of the ultimate triumph of good over evil, that have earned it a special place among the other texts in this series.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.15.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.