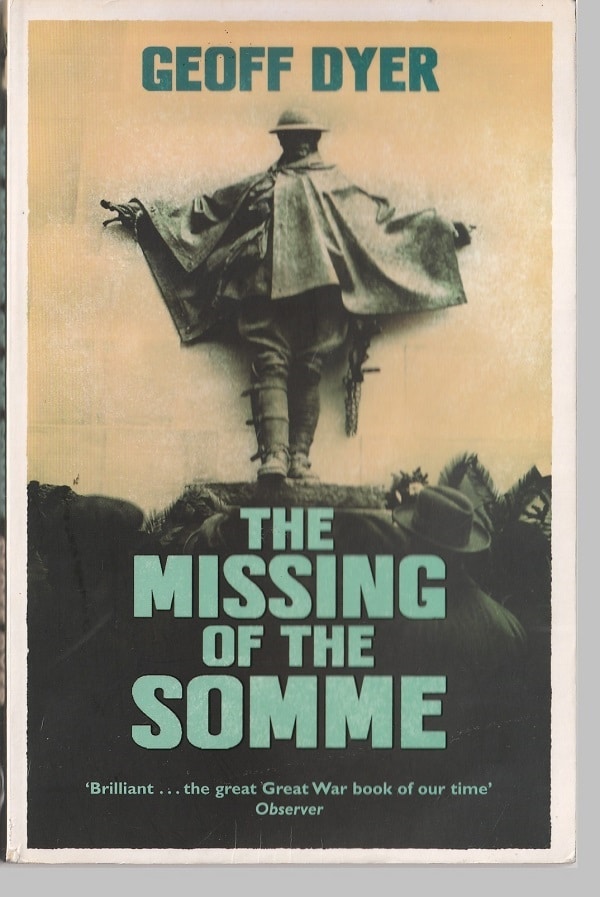

Two images from The Missing of the Somme, the 1994 book by Geoff Dyer about memory and the Great War, now called World War I:

- Young men, lined up at the start of the war to enlist.

- John Singer Sargent’s painting Gassed, a long horizontal work with three levels — the bottom, a chaos frieze of bodies; the middle, a line of 11 soldiers, many of them blind — the blind leading the blind — right hand on the shoulder in front; and the top, the endless, empty sky.

Several times in his meditative, impressionistic book, Dyer mentions the many photos of enlistees in those early days of the conflict. The present-day viewer knows what is to come, and Dyer writes:

The young men queuing up to enlist in 1914 have the look of ghosts. They are queuing up to be slaughtered; they are already dead.

And, thirty pages later, he writes:

This is why — to return to an earlier theme — the photographs of men queuing up to enlist seem wounded by the experience that is yet to come; they are tinted by the trenches. The recruits in 1914 have the look of ghosts. They are queuing up to be slaughtered; they are already dead.

This is an example of Dyer’s approach in writing The Missing of the Somme, a tortuous twisting and turning within a dark set of emotions and impressions, circling back and looking again at something, now from a different vantage or the same vantage, now with new words or the same words.

Anyone who, in the past century and more, has glanced at such photos — they could be guys from the local softball team, a cigar club, young accountants out on a holiday — has known how great the death toll will be. Was.

One million British soldiers dead.

Eight million or more military deaths of all participants, allies and enemies, in the carnage.

“Bloody rugs”

The Missing of the Somme is a book written by a Briton, born in 1958, being read, in this case, by me, an American born in 1949.

As a reader, I clearly see that, for Dyer, the Great War holds a much greater grasp on his past than it does for me. The United States was late into the war, and its soldiers missed the worst of the mindless, pointless trench warfare.

To illustrate the way it was before the Americans arrived, Dyer quotes an American, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who, in his novel Tender Is the Night, has a character say to another:

“See that little stream — we could walk to it in two minutes. It took the British a month to walk to it — a whole empire walking very slowly, dying in front and pushing forward behind. And another empire walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloody rugs.”

Fitzgerald’s character says that men of future generations could never do this sort of senseless dying: “This took religion and years of plenty and tremendous sureties and the exact relation between the classes.”

For a Briton, such as Dyer, the Great War was a shuddering, relentless, long-suffered national trauma. He writes:

It was as if a terrible plague had swept invisibly through the male population of the country — except there were no bodies, no signs of burial, no cemeteries even.

Ten percent of the males under forty-five had simply disappeared.

“The Greek word psyche”

The title of Dyer’s book, The Missing of the Somme, has several meanings.

The word “missing” deals with multiple levels of experience. It suggests remembering the Somme, i.e., the War, in the sense of knowing that it is over and done (gone missing). And it suggests forgetting (missing the experience of remembering).

It suggests the war as a vast emptiness, a huge vacuum, and a great loss — the years that were lost, the men missed, in the fighting of battle.

And there is a very specific meaning — a memorial at Thiepval, a memorial to THE MISSING OF THE SOMME, which “seems almost ugly, its hulking immensity dominating the landscape for miles around.”

The names of 73,077 soldiers, English and French, are inscribed on the memorial’s 16 brick piers, faced with Portland stone, the dead from the battle. In 1917, the poet John Masefield was at this spot and wrote in a letter:

“Corpses, rats, old tins, old weapons, rifles, bombs, legs, boots, skulls, cartridges, bits of wood & tin & iron & stone, parts of rotting bodies & festering heads lie scattered about. A more filthy evil hole you cannot imagine.”

At a small cemetery attached to the Memorial, Dyer walks through rows of crosses, row after row:

The only sound is of humming bees, of light passing through trees, striking the grass. Gradually I become aware that the air is alive with butterflies. The flowers are thick with the white blur of wings, the rust and black camouflage of Red Admirals, silent as ghosts.

I remember the names of only a few butterflies but I know the Greek word psyche means both “soul” and “butterfly.” And as I sit and watch, I know also that what I am seeing are the souls of the nameless dead who lie, here, fluttering through the perfect air.”

“Exalted emotion”

At another time, at another small cemetery, Dyer writes:

Scarves of purple cloud are beginning to stretch out over the horizon, light welling up behind them. The sun is going down on one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Dyer comes, in this moment, to know that some part of him would forever be calmed by the memory of this place and “the vast capacity for forgiveness revealed by these cemeteries, by this landscape.”

Yet, he also knows that his presence changes nothing. The place would be the same without him as it is with him. And maybe that’s what one cemetery visitor meant by writing in a guest book about “lonelyness” —

knowing that even at your moments of most exalted emotion, you do not matter (perhaps this is precisely the moment of most exalted emotion) because these things will always be here: the dark trees full of summer leaf, the fading light that has not changed in seventy-five [now one-hundred-and-three] years, the peace that lies perpetually in wait.

“The painting’s compassion”

Midway through The Missing of the Somme, Dyer writes about Sargent’s painting:

In Gassed there is little suffering. Or rather, what suffering there is is outweighed by the painting’s compassion. In spite of the vomiting figure the scene has almost nothing in common with Owen’s vision of the gas victim whose blood comes “gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs.”

What Sargent has depicted, instead, is the solace of the blind: the comfort of putting your trust in someone, of being safely led….In Sargent’s painting coughing and retching are absorbed by the tranquility of the evening.

The lyricism of [novelist Jean] Rousaud’s description [of a gas attack] is beginning to make itself felt again as air and men convalesce, reasserting their capacity for tenderness.

“The ultimate mystery of the First World War”

“Their capacity for tenderness” — this puts me in mind of the words of John Keegan, a uniquely sensitive military historian who used the word “love” at the end of his 1999 book The First World War.

As he is bringing his 427-page history of World War I to an end, he does not mention the millions of dead or the botched generalship or the gore and horror of the war in the trenches. Instead, it is the comradeship of the soldiers, their affection for each other, their emotional ties to each other, that are in his final thoughts for the reader.

And the way these connections enabled these men to endure the unendurable:

Men whom the trenches cast into intimacy entered into bonds of mutual dependency and sacrifice of self stronger than any of the friendships made in peace and better times.

That is the ultimate mystery of the First World War. If we could understand its loves, as well as its hates, we would be nearer understanding the mystery of human life.

The intimacy of the soldiers. Their capacity for tenderness.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.11.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.