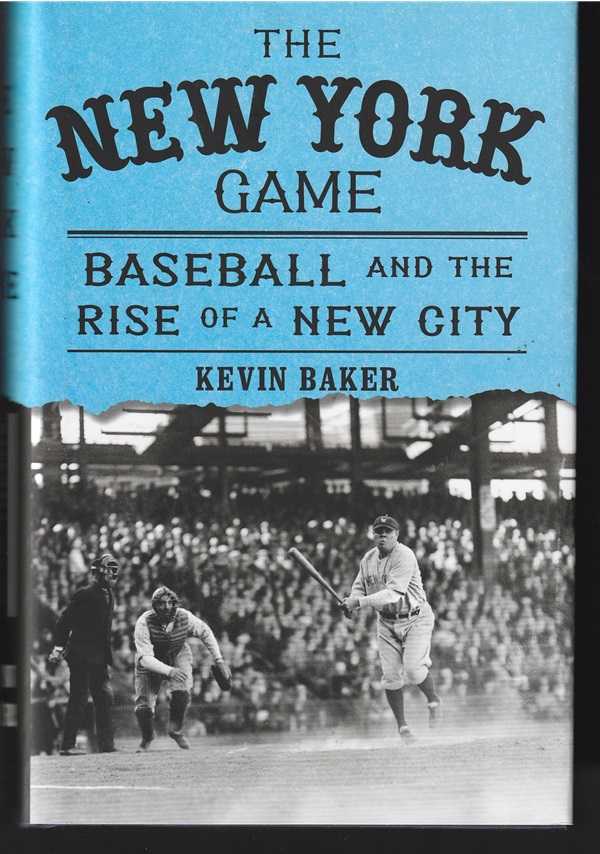

The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City is Kevin Baker’s love letter to the city and the sport and the way they have intertwined for nearly two centuries.

In its opening pages, the lifelong New Yorker writes:

Baseball is a game that grew up inextricably linked to the pace, and the customs, and the demands of New York….For the last two centuries, the game’s trajectory has followed the city’s many rises and declines, its booms and its busts, its follies and its tragedies.

This is the story of that city and its game. It is, as well, a fan’s story….

The game endures, this ineffable, silly thing, to which too much attention is paid; this uneasy, wobbly, wonderful contraption which is always threatening to blow itself up, and which in this manner is never more like the city from whence it sprang.

At 475 pages, The New York Game is quite a hefty billet doux — and it only covers a century, ending in 1945 with the conclusion of World War II.

Although Baker gives no indication, it seems apparent that a second volume has to follow to look at all that has changed, for better and worse, in New York and in baseball, and to revel in all the characters of the past eight decades in the city and the sport.

Verve, charm, insight

It’s doubtful that anyone will complain the book’s heft. Baker, a novelist and an historian, writes with verve, charm, delight and insight about seemingly every aspect of baseball and New York. Such as:

It’s doubtful that anyone will complain the book’s heft. Baker, a novelist and an historian, writes with verve, charm, delight and insight about seemingly every aspect of baseball and New York. Such as:

- John Montgomery Ward, a key player in the 1880s on the New York Gothams, later Giants, “came into his own [in New York], taking one Broadway diva for his wife and another for his mistress, while still finding time to earn both political science and law degrees from Columbia University…By the time he was thirty years old, Ward spoke five languages and was a practicing attorney, his courtroom style described as ‘shrewd, quick-witted and humorous, smiling and sarcastic.’ ”

- By the 1940s even the high-brows were celebrating “the Americanization of Brooklyn” or, more accurately, acknowledging “that the haimishe, polyglot borough of Brooklyn might be the real heart of the nation. Brooklyn, drawn from all over the world. With the onset of the war — a war against the forces of racial purity and absolutism — the borough’s ethnic composition became an active virtue.”

- Fabled Giants manager John J. McGraw, according to journalist Heywood Broun, had the wonderous ability to “take kids out of the coal mines and out of the wheat fields and make them walk and chatter and play ball with the look of eagles.”

- Nick’s, a late nineteenth century restaurant in the entertainment district, was the hangout of celebrities and underworld types and known for its “barbaric ritual of beefsteak: slabs of hickory-broiled beef, smeared with butter and eaten solely by hand — no utensils allowed — and washed down with countless mugs of ale.”

- The two principal owners of the new American League franchise that became the Yankees — Frank Farrell who “looked like skullduggery walking” and owned numerous gambling operations and crooked cop Big Bill Devery — later sold the team and in a few years were “dead broke, and then just dead, their ill-gained fortunes returned from whence they sprang, to banquet halls and stuss tables, barrooms and bordellos.”

- Brooklyn manager Leo Durocher’s dating strategy bore more than a little resemblance to a certain twenty-first century politician’s words on an Access Hollywood tape.

- A violent thunderstorm in 1929 set off a rush for shelter in the rightfield bleachers, resulting in a panic that killed one man immediately and badly injured several others, including a seventeen-year-old girl named Eleanor Price who was carried by Babe Ruth and others to the Yankee locker room where Ruth “knelt beside her on the floor, stroking her head until she died.”

- “For [Depression-era] New Yorkers, the more pressing question was, how to root for such a team? This bloodless, humorless corporate juggernaut. Here was the origin of the old saw: ‘Rooting for the Yankees is like rooting for U.S. Steel.’ …[S]heer domination and efficiency were not altogether unwelcome…But there needed to be more. There needed to be at least some evidence of a soul in the machine…It was Gehrig who, ultimately, made the Yankees human….”

- “New Yorkers loved the sheer, frenetic energy of [Fiorello LaGuardia], the way he stamped his own pugnacious face on the vast, impenetrable workings of the city’s government. He was ubiquitous….’It seemed as though the town had been invaded by an army of small, plumb men in big hats,’ the New Yorker noted. ‘He was everywhere.’ ”

- From the nineteenth century through today, the major leagues are “the most complete and enduring cartel in American history…directly against not only potential business rivals but also the customers, whom they charge ever-higher prices; the general public, whom they constantly lobby for subsidies; and their own employees, whose compensation, or even right to have anything to say about their compensation, baseball’s owners still contest.”

- In 1942, a German U-boat snuck past Coney Island, enough for the twenty-eight-year-old commander Reinhard Hardegen, who had visited New York as a child, to look and later say, “I cannot describe the feeling with words, but it was unbelievably beautiful and great…[I] wondered what form the life of the city was taking at this hour…Were the Broadway shows just letting out?”

- Casey Stengel, as a Dodger outfielder in 1912-1919, was a “jug-eared, freckled, hot-tempered son of a Kansas City businessman and insurance agent,” nicknamed then both Dutch and Irish, who “had dropped out of high school and later dental school for the chance to play professional baseball. ‘I was a left-handed dentist who made people cry.’ ”

Rooted in history

Those twelve examples give you an idea of Baker’s writing and the sort of topics he deals with as he moves through the history of baseball and New York during the century that this book covers.

His writing is endlessly fascinating as he stresses the stories and personalities of the sport and the city, using game accounts and statistics only as a skeleton for his book.

Much of what Baker deals with isn’t new, yet he brings a vibrant active curiosity to the page and to his lively synthesis of scenes and people. This is not just another book about baseball, just another book about New York.

And there is much that will surprise and interest even those most knowledgeable about the city and baseball.

For instance, the title of Baker’s book The New York Game isn’t a piece of triumphal puff. It’s rooted in history.

The Philadelphia game, the Massachusetts game

The game that Ted Williams played, that Cal Ripkin played, that Shohei Ohtani plays today is the New York game, the sort of baseball that was played in the city in the mid-nineteenth century.

As Baker explains, by the Civil War, nearly every region in the nation had its own game involving a ball and a bat, such as wicket in Connecticut (played by George Washington at Valley Forge).

The New York game’s main competitors were Philadelphia town ball and the Massachusetts game. The field for the Philly game was arranged around a circle of four stakes, twenty feet apart, along with a fifth stake in the middle serving as a sort of substitute pitcher’s mound….

The Massachusetts game was something else again. It was played not on a diamond or a circle but a square. There were four bases, one at each corner….There could be seven to fourteen players a side….But the big differences were these: runners were retired by being hit with a thrown ball, and there was no foul territory or even rules that runners had to stay within the baselines.

There is the promise of a certain wonderfully daft anarchy embedded in these rules or anti-rules, a sort of baseball combined with dodgeball.

“Seminal contribution”

Despite such competition, the New York game was dominant game in the Northeast at the start of the Civil War, and then, because of the war, it was spread throughout the rest of the county.

That was due, Baker writes, to the New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club, one of two teams to play what may have been the first baseball game ever played in 1846.

The Knickerbockers “made their seminal contribution, in consolidating, formalizing, and studiously jotting down what other ball clubs around the city had already improvised.” He goes on:

The “Knickerbocker Rules” decreed the following: The infield was to be shaped like a diamond, with four bases, including home plate. No physical interference with fielders by base runners was allowed….There were three outs to an inning, and batters were retired by striking out, by being tagged or forced at a base, or by a ball caught on a fly or the first bounce…And there was a balk rule, although no one understood it even then.

There were aspects to the rules, such as that one-bounce out, that would be eliminated or refined over time. But the core of baseball as we know it was in those rules.

And, by the 1890s, the baseball “was now clearly recognizable, as the same game that we know it to be today.” The New York game.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.28.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.