In the dark night and under the icy water, Cordelia Gray, lungs bursting, is swimming for her life. She knows that the sea is death if she cannot find the surface somewhere out from where she is and up above her.

And, then,…she saw the water above her lighten, become translucent, gentler, warm as blood, and she thrust herself upward to the air, the open sea, and the stars.

So this was what it was like to be born, the pressure, the thrusting, the wet darkness, the terror, and the warm gush of blood. And then there was light.

P.D. James could write.

Born Phyllis Dorothy James and, later in life, honored as Baroness James of Holland Park, she lived 94 years, dying in 2014. Her original career was as a British civil servant, and it wasn’t until her early 40s that she published, in 1962, her first novel Cover Her Face.

During the second half of her life, James wrote 19 novels, 14 of which were mysteries featuring the poetry-writing, intensely observant and self-questioning Adam Dalgliesh, a high-ranking detective with the New Scotland Yard.

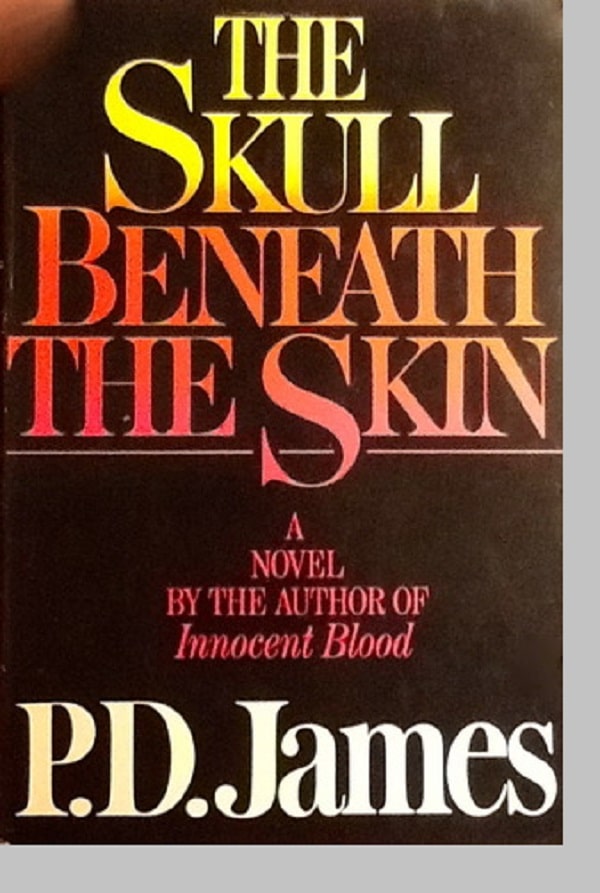

Cordelia Gray was at the center of two other mysteries — An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1972) and The Skull Beneath the Skin (1982), the novel in which she finds herself swimming for her life.

Talk to and confide in

James, it seems, had a deep affinity with the brooding Dalgliesh, fashioning nearly a score of novels around him over a 46-year period, about one every three years.

She gave up on Cordelia after two novels, and, as a reader, I’m sorry for that.

Dalgliesh is unlike most mystery-book detectives in the richly complex internal life that James created for him and put on display for readers. Nonetheless, he is still always the police detective solving crimes.

Cordelia is a young woman who pretty much stumbles into the job of a private detective. She is bright, perceptive and alert, but not one for following rules. At least, in the two novels about her, she fails to keep a professional distance, getting more mixed up with the people who become murder suspects than, say, a police detective would.

Indeed, in both novels, she is considered a suspect for a time, and, in both, she withholds information from the police even though it gets her in trouble.

While readers meet Dalgliesh in mid-career when he is fully formed as a professional, Cordelia is in her 20s in her two books. She has great investigative instincts, and, even more, she is the sort of personable woman whom people, even killers, like to talk to and confide in.

I would have liked to see her get a little more seasoned at her job — and at life. I suspect that, had James written more about Cordelia, the character would also have had to deal with the pitfalls for romance.

As it is, the only vaguely romantic aspect of her life that is told in the James novels is that Cordelia and Dalgleish share an edgy respect for each other and have dined together. That flirtation, if flirtation it was, is over by the start of The Skull Beneath the Skin.

“Like the predator he was”

I don’t know if James ever addressed her decision to limit Cordelia to two novels. (She didn’t mention it to me in the two times I interviewed her for the Chicago Tribune, but, of course, that was for new Dalgleish books.)

I suspect that she had more in common with the middle-aged police detective than with the somewhat unfocused rookie private eye. She had, after all, been a civil servant for three decades, and, when she started writing, she was already middle-aged.

Perhaps she was bored with someone so new to adulthood. In The Skull Beneath the Skin, Cordelia is off-stage for much of the middle section, and the action is dominated by the two investigating police, both of whom are sharply drawn and interestingly idiosyncratic.

Sergeant Robert Buckley was young, good-looking, and intelligent, and well aware of these advantages. He was also, less commonly, aware of their limitations.

He is, in addition, something of a schemer, the opposite of an idealist, a pragmatist intent on success and willing to adjust his sights based on the likelihood of coming out on top. Hence, his decision to join the police.

He judged that success would come quickest for a job for which he was over- rather than under-qualified and where he would be competing with men who were less rather than better educated than himself.

Although he recognizes the need to work devotedly for his chief, Buckley chafes at keeping quiet and keeping his place while the red-haired Chief Inspector Grogan does the case his way.

Grogan looked as he always did before a case, silent and withdrawn, the eyes hooded but wary, the muscles tensed under the well-cut tweed, the whole of that powerful body gathering its energies for action like the predator he was.

“First human contact”

In contrast to these tough cops, Cordelia comes across as all too human, all too soft.

After her discovery of a murder victim, she operates with professional skill and sense. Then, a minutes later, she tells other people about the slaying and breaks down:

And then her control broke. She gave a gasp and felt the hot tears coursing down her face. Ivo ran to her and she felt his arms, thin and strong as steel rods, pulling her toward him. It was the first human contact, the first sympathetic gesture, which anyone had made since the shock of finding [the] body.

I liked Cordelia as a central character who felt the yearning for human contact. That, obviously, was going to complicate things if she showed up in other novels.

I don’t begrudge James her decision to turn her writing away from Cordelia.

In his own way, Dalgliesh is very human, too. But he is certainly more of a loner, someone who is used to being alone and likes being alone.

Come to think of it, that’s what makes P.D. James books so rich — she created characters who had human idiosyncrasies and deeply human feelings. Some, such as Buckley and Grogan, kept theirs well-defended.

Through James, though, Cordelia and Dalgleish showed much more of their full humanity.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.17.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

A very good comment I find it a pity that a character so nicely created was only given two novels.

Maybe linking Cordula with the significantly older Dalgliesh did not work out as intended by the author and she abandonded the girl.

I just read the book and can’t believe this should be the end of Cordelia Grey

I think James found a way to work a Cordelia-type character into the Dalgliesh books via Detective Inspector Kate Miskin. In “Original Sin,” Kate is one of two central police characters and Dalgliesh plays a pretty minor role. See my review: https://patricktreardon.com/book-review-original-sin-by-p-d-james/