Sonja Livingston’s mother led an irregular life, giving birth to seven children, often without a husband, but she still attended Corpus Christi Catholic Church with her kids, striding up when it was time to receive communion.

Sonja, though, missed First Communion with her class because her mother had moved the kids elsewhere for a time. Not a problem, said her friend Angie when, a couple years later, the family returned to the parish in a low-income Rochester, N.Y., community. She could borrow Angie’s white dress and do it solo.

And so she did, at a Thursday night folk mass after which everyone headed down to the basement hall where parishioners had prepared a party with a cake and punch and even presents. When they got there, though, they discovered that someone — girls from a local family even poorer than Sonja’s were the prime suspects — had stolen the presents.

At the time, Sonja thought that the loss of the presents hadn’t mattered, but, now, in her late forties and an English professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, she realizes she’s “still tracing the shape of their absence.” She thinks of those girls suspected of the theft:

“Poverty’s cruelest trick is turning human beings into ravenous birds. And just like that she’s with me again, the girl I used to be, reminding me who I am. Yes, church captivated me as a child, but hadn’t I also been drawn by hunger?”

“The most beautiful thing I knew”

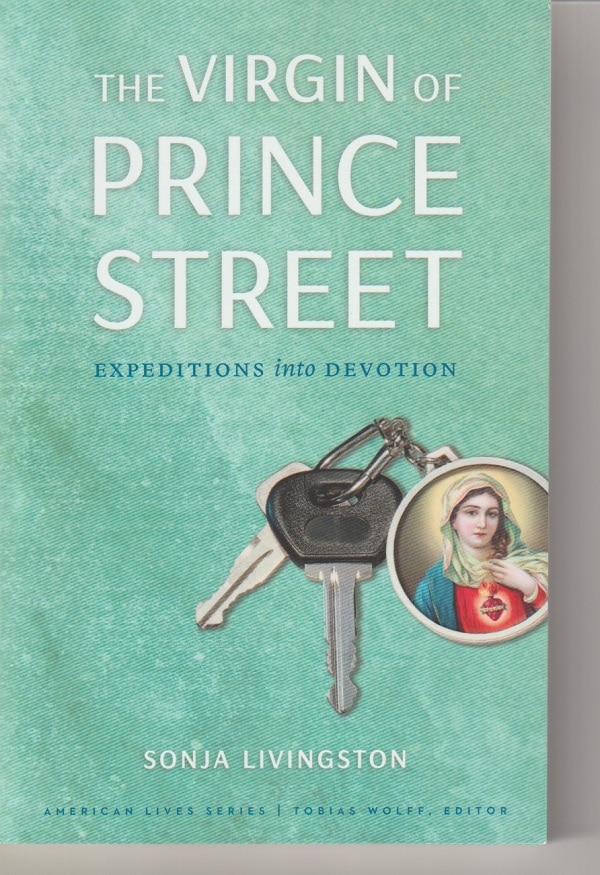

The Virgin of Prince Street (University of Nebraska Press, 166 pages, $17.95) is about Livingston’s return to the church of her childhood — both to Corpus Christi, now called Our Lady of the Americas, and to Catholicism.

It’s a very personal journey, but isn’t that true of everyone’s spiritual odyssey? Like all of us, Livingston’s was a multi-faceted hunger. Part of her hunger was for beauty, outside and in.

“I’d loved the sandstone building on East Main and Prince Street for as long and as hard as I’ve ever loved anything. With its high-flung ceiling and gothic arches, the church was the most beautiful thing I knew. And I was more beautiful in it. Not physically — though a mirror in the basement did, in fact, soften my features; I only mean that I was a better version of myself at Corpus Christi. Everyone was.”

Like many American Catholics of the second half of the 20th century, Livingston writes that “my own skepticism thwarted any hope of theological convention.” In The Virgin of Prince Street, she does not write much about her differences with particular church teachings nor about her distress at the clergy pedophilia scandal.

Like many American Catholics of the second half of the 20th century, Livingston writes that “my own skepticism thwarted any hope of theological convention.” In The Virgin of Prince Street, she does not write much about her differences with particular church teachings nor about her distress at the clergy pedophilia scandal.

She returns to Corpus Christi and begins various spiritual searches — the expeditions of the subtitle — because of Catholicism’s deep resonance for her.

“A better version”

The faith she exhibits has nothing to do with intellectual debates or rules and regulations. Her faith — which is to say, her searching — goes deeper than thought. It goes to a core where words don’t work although Livingston does her best to explain what she is feeling and doing.

It is about returning to a place where she is “a better version of myself” and so are those parishioners she comes to know.

Faith and violence

But faith doesn’t always do that. Faith can lead to violence.

In the 1985, the statue of the Virgin at Ballinspittle was one of many Mary statues in Ireland that were reported by onlookers to move as if alive. Then, on Halloween night, three Evangelical Protestant men “pulled up, jumped from their car, and attacked the statue. They destroyed the Virgin’s face with hammers and axes while taunting the pilgrims.”

A year earlier, faith of a different sort seems to have been at work in the actions of a 15-year-old schoolgirl who went to the statue in her school uniform and gave birth. The infant was dead when the girl was found by other children several hours later, and the frozen young mother herself soon died.

Livingston, who visited the statue during a recent tour of Irish shrines, writes:

“Why did she go there, that girl? Was the statue, slick with January drizzle, the warmest place she knew? Cold to the touch, yes. Fashioned of concrete and plaster, but like cotton compared to…the country that made birth-control impossible…”

“Letting herself believe”

There is anger in those words, but Livingston goes deeper:

“Perhaps, she thought as she approached the church — letting herself believe in the beautiful way only the most desperate do — perhaps Our Lady will help.”

There is ambiguity here, and some believers have a hard time with ambiguity. Livingston, though, embraces it. She doesn’t look for flashy miracles, but, in her book, she seems, on every page, to be describing the small miracles of everyday faith.

The small miracles that all of us experience when we live as better versions of ourselves.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.6.19

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.