All art is strange, disquieting.

Read Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Or attend a performance of Shakespeare’s King Lear. These are idiosyncratic creations to the extreme. Nothing else quite like them, even works by the same author.

Or take a look at the Wilton Diptych (1395-1399).

If you’re not an expert in the visual arts, if you’re simply an admirer, it’s easy enough to develop a sense of art history that leaves you familiar with a great many works by a great many artists. Images of Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo’s Last Supper, for instance, add richness to your life with their beauty and rightness.

But how often do you focus on them as something other than pretty pictures, other than pleasing objects? Think about it: David’s seventeen feet tall! And something extraordinary and very complex is going on in that Last Supper.

The same is true with the Wilton Diptych.

A sad story

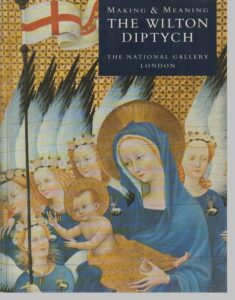

As its subtitle indicates, Dillian Gordon’s The Wilton Diptych: Making & Meaning looks at how this portable altar piece, made up of two hinged panels painted on both sides — “one of the most beautiful paintings every made” — was fashioned for the ill-starred English King Richard II.

How ill-starred? Richard suddenly became king at the tender age of 10. He didn’t seem to have had a good idea of how to reign, or maybe he didn’t have the right advisers. His beloved wife Anne died.

Then, at 33, shortly after the Wilton Diptych was painted, he was deposed by Henry Bolingbroke (Henry IV) who put the former monarch in a castle where, four months later, he died — apparently, starved to death.

It’s a sad story that, in a way, is embedded in the artwork, which gets to the “meaning” part of Gordon’s subtitle.

The diptych

The hinges in the Wilton Diptych — named for the place it was held in the century before, in 1929, it came into the collection of the National Gallery in London — allowed the outer panels to be closed, thus protecting the two inner panels when the altarpiece was being moved from one place to another.

Those outer panels, exquisite in their way, have suffered damage over the past six hundred years while the inner panels are, with minor exceptions, as vibrant as they were when first fashioned.

These inner panels — each 20.9 inches by 14.6 inches — show, on the left, a kneeling Richard and three saints, John the Baptist, King Edward the Confessor and King Edmund the Martyr standing behind and next to him and, on the right, the Virgin and Christ Child, surrounded by eleven winged, halo-ed angels, one of whom is holding a banner.

Art sending a message

At first glance, the Wilton Diptych seems to be a straight-forward depiction of Richard, as an earthly ruler, who, supported by the three saints, kneels in homage to the Baby Jesus in the arms of his mother.

the Wilton Diptych seems to be a straight-forward depiction of Richard, as an earthly ruler, who, supported by the three saints, kneels in homage to the Baby Jesus in the arms of his mother.

But at the time the artwork was created, Richard was in his late 20s and wore a small chin beard and a moustache. So why is he shown with clear cheeks and flowing blond hair, looking almost feminine?

The best guess, according to Gordon, is that the scene being depicted is showing the prepubescent king at his coronation. In other words, this painting sets out to document Richard’s right to the throne.

That idea is buttressed by the many details in the painting that make the art essentially a celebration of his kingship. And that banner? There’s a theory that, in the story being told, Jesus has given the banner to Richard as his designee in England, and Richard has just given it back to his Lord as a sign of his fealty.

To whom?

So, in a way, this is art as propaganda — art communicating a message. But to whom?

The Wilton Diptych, during the king’s lifetime, apparently was never seen by anyone except him and the people around him. Not the English people. Not the nobles.

The best guess is that it belonged to and was used by Richard. So, it would seem that the goal of this work was to convince the king that he had a right to be king — a divine right.

That’s pretty sad inasmuch as Henry VIII didn’t need someone to remind him that he belonged on the throne. Or Elizabeth I. Or Henry V.

Or Richard’s nemesis Henry IV.

Unlike anything else

In one way, it is somewhat helpful to know this information when looking at the work. But I don’t think it’s necessary. Or probably advisable most of the time.

I think what happens is that the real-world concerns that go into making a masterpiece tend to give it grit and strangeness. The more material — ideas and goals and images — that an artist has to juggle in creating a work, the richer the art.

The viewer who doesn’t know those concerns experiences this richness as an aspect of the art, of what the eye sees. This still happens when the viewer knows the details of the history and goals of the artist and patron, and, overlaid on that, is an experience of the art in the mind of reasoning.

That mind-stuff can dovetail with the eye stuff. However, it seems to me, it can also distract.

So, when we look at the Wilton Diptych, we see how a great artist has pulled together all this complexity, synthesized it and brought to life something unsettlingly attractive. We see this whether we know the back story or not.

Who the great artist was, however, isn’t known. Nor is the artist’s nationality known. What is clear is that this work is unlike anything else being done at the time. As Gordon writes:

“The Wilton Diptych can be compared superficially to some contemporary panel paintings and manuscript illuminations but fundamentally to none.”

Gordon adds that scholars have theorized a wide range of possible influences, including Simone Martini. And that’s what got me looking at Martini’s The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus, created in 1333, six decades before the diptych.

The triptych

The Annunciation — a much larger work, nearly nine feet tall and 10 feet wide — is a triptych, created by Martini with the help of his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi.

Like the Wilton piece, it was made with tempera and a lot of gold leaf but without all the sumptuous semi-precious lapis lazuli that gives the right panel of the later English work an almost other-worldly grace.

The central panel of the Annunciation shows the angel Gabriel kneeling to Mary and telling her that she will conceive through the Holy Spirit and give birth to the Son of God, Jesus — if she accepts.

Mary’s body language

I don’t know specifically what Martini and his brother-in-law were trying to say in this work. Whatever it was, there is an unsettling quality to the painting, particularly in the figure of Mary.

Here, look at Mary as the angel is telling her that she has been chosen to be the mother of God.

This is not, for her, a moment of celebration. Indeed, she is turning away from Gabriel, seeming to be pulling her cloak to cover her, as if to hide. The body language says the message just delivered has twisted her, outside and in, in the most awkward way.

And look at her face — at her slit eyes, her small mouth in a frown.

All the exultant gold here says one thing. Mary’s body and face say another.

Unsettling

In both the Wilton Diptych and Martini’s Annunciation, there is a tension that’s undeniable. Look at them again, this time together:

They are both resplendent. Both almost blindingly beautiful. And both strange.

Richard, the boy, may have a wan smile on his face, and he is undoubtedly the focus of everyone’s attention (except for one perhaps distracted angel). But something’s not right.

The King being portrayed was no kid when the painting was made, but an adult whose throne would soon be taken from him. In this work that seems to work so hard to buttress the belief that the crown belongs to Richard, he is portrayed as small and vulnerable, smaller than any other figure except Jesus who, at least, is being held in his mother’s arms (and, after all, is God).

Richard is alone.

With the Annunciation, the tension has to do with the two different stories — the one of great joy that the Son of God will become man, and the other of great sorrow, that of Mary who will watch him grow, suffer and die.

In contrast to Richard, Mary is the largest figure in the composition. If she were to stand, she would be taller than the saints on either side of the triptych and taller than even the angel.

The tiny angels at the top of the work are joyful. Gabriel is delivering a message that is full of wonder and awe, but Mary is corkscrewed in pain and a premonition of the sorrow she will bear.

Mary is alone.

The tension in both works is what makes them masterpieces.

It makes them strange and unsettling.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.1.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.