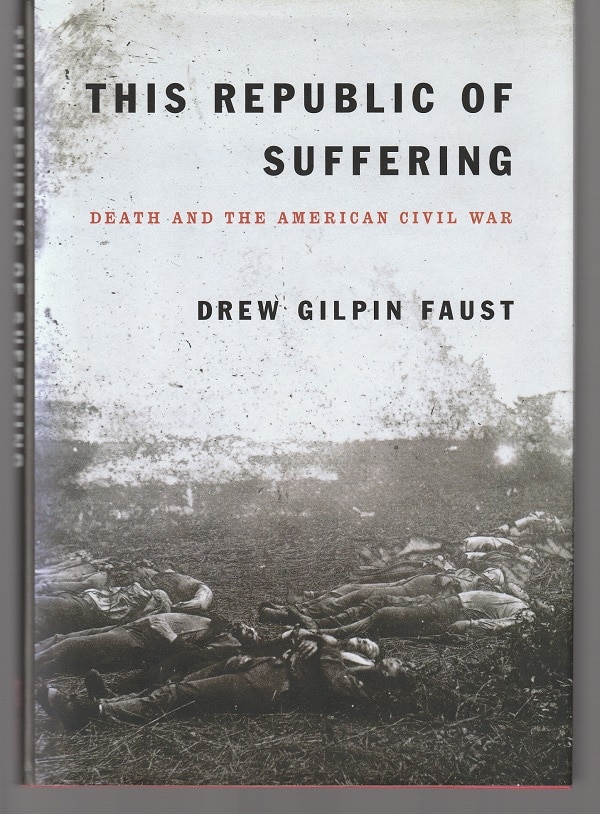

Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War is an extraordinary achievement that answers a needed but previously unasked question:

How did Americans deal — culturally, materially and, above all, emotionally — with the grisly and inconceivable reality of more than 600,000 soldier deaths during the Civil War?

In many ways, Faust’s book is reminiscent of John Keegan’s 1976 work The Face of Battle, a groundbreaking study of the experience of foot soldiers in the medieval battle of Agincourt, the Napoleonic Era confrontation at Waterloo and the World War I bloodbath in the Somme. Previously, no historian had asked: What was it like on the front lines in battle? In asking and answering that question, Keegan broadened and enriched the study of battle in every future book of military history.

Similarly innovative, This Republic of Suffering takes up a question that has been overlooked despite tens of thousands of books on the Civil War and its era.

No previous historian has written about the war without dealing, usually in great numerical detail, with death — the number of casualties, the strategies of generals, the tactics of field officers, the technology of weapons, from bayonets to sabers, from repeating rifles to cannons. And there is no aspect of Faust’s book that hasn’t been touched on by earlier writers.

The reality of death

What Faust has done, however, is to bring the reality of death to the center of the discussion, to examine in great exactness and empathy the many ways in which the dying of soldiers, North and South, wove itself into American life during the four years of war and for many decades afterward.

Her eight chapter headings give a sense of the breadth and depth of her book and the questions that she addresses:

- “Dying” — How did the soldiers think about the possibility of approaching death? How did the fighters deal with the body and memory of a dead comrade?

- “Killing” — How did the soldiers overcome their deeply rooted ethical training to be able to actively work to kill enemy men?

- “Burying” — When and how were the bodies of dead soldiers buried? When were they left to the elements?

- “Naming” — How well were armies able to attach names to the bodies of their soldiers? What happened to unidentified bodies? How could a soldier be determined to be dead if his body had been literally blown to bits by an explosion or a cannon ball?

- “Realizing” — How did the families and friends of the dead come to “realize” that, despite their disbelief, their loved one was dead and reconcile themselves to this loss? Especially when the loved one’s body was never found?

- “Believing and Doubting” — How did the belief systems of Americans cope with the deluge of death that occurred on the Civil War battlefields? How did Americans find meaning in this carnage?

- “Accounting” — In the aftermath of the war, what was done to locate the scattered graves of Union and Confederate soldiers? How were they gathered into local and national cemeteries?

- “Numbering” — What was done to try, after the war, to determine specifically how many soldiers had died?

“Anxious to know, yet dreading to hear”

There is overlap among these chapters. For instance, it was sorrowful for a mother or father to get word that a soldier son had died, but many parents and loved ones were held in “harrowing suspense” by a lack of definite news. Indeed, they found themselves hungry for any information, even the worst of information. As one official wrote:

“A mother has not heard anything of her son since the last battle; she hopes he is safe, but would like to be assured — there is no escape — she must be told he has fallen upon the ‘federal altar’; an agony of tears bursts forth which seem as if it would never cease…

“A father…with pale face and tremulous voice, anxious to know, yet dreading to hear, is told that his boy is in the hospital a short distance off;…while tears run down his cheeks and without uttering another word [he] leaves the room.”

“Slaughtered like animals”

In the Victorian culture of the mid-19th century, dying a Good Death was the hope and expectation — coming to the end in a calm way while making peace with God and saying goodbyes to family. But, on Civil War battlefields, that hope was impossible to achieve.

Comrades did their best to send back word to the dead man’s home that his final moments were tranquil and filled with faith. But they had seen what they had seen, and they knew that his death and all the others around them did not match the expected way that a man was supposed to die. As Faust notes:

Narratives of the Good Death could not annul the killing that war required. No could they erase the unforgettable scenes of battlefield carnage that made soldiers question both the humanity of those slaughtered like animals and the humanity of those who had wreaked such devastation.

Death, she writes, remained unintelligible for the soldiers and those left behind — or, as Herman Melville wrote, “a riddle…of which the slain/Sole solvers are.”

“Occurred in bunches”

In looking at the death of soldiers in the Civil War, Faust weaves together anecdotes and information from North and South.

She notes that Mary Chestnut, the author of an important and vivid diary of the war years in the South, recorded that, in South Carolina, the sound of the funeral march seemed incessant. And Faust adds:

Many small communities on the other side of the Mason-Dixon line found the same. In Dorset, Vermont, home of a quarry that provided thousands of tombstones for Gettysburg, 144 men volunteered and 28 died. Funerals in Dorset seemed never ending and sometimes occurred in bunches when a unit with numbers of local men suffered heavy losses.

“One way to make death real”

This Republic of Suffering looks forthrightly and with clear-eyed compassion at a wide range of topics having to do with death.

Such as fashion.

To embody — quite literally — death was one way to make it real….In the mid-nineteenth century respectable Americans, or those who aspired to be considered among their ranks, customarily observed a formal period of bereavement after the death of a spouse or relative.

Women wore black to show their loss, and there were conventions of how long to wear black and then how to slowly transition into half mourning with clothes of lavender, gray and purple.

The women in the South were more likely to be in mourning than their sisters in the North. Of the 880,000 Confederate soldiers, 29% died, compared to 17% of the 2.1 million Union fighters.

In the South, Faust writes, the sorrow created “a uniformed sorority of grief.” And she quotes Lucy Breckinridge of Virginia:

“There were so many ladies here, all dressed in deep mourning, that we felt as if we were at a convent and formed a sisterhood.”

In Tennessee, a visitor told Nannie Haskins that she looked good in the black she was wearing to remember her brother’s death, and the teenager wrote in her diary:

“Becomes me fiddlestick. What do I care whether it becomes me or not! I don’t wear black because it becomes me…I wear mourning because it corresponds with my feelings.”

“Off the dead”

The sheer magnitude of Faust’s research and the intricacy of her synthesis is flatly astonishing, especially given that she was pioneering this comprehensive approach to the consideration of death in the Civil War culture.

This Republic of Suffering is an important touchstone book for future historians and one that anyone interested in the Civil War needs to read.

Nonetheless, it must be said that, given its subject and Faust’s refusal to look away from hard truths, reading this book can be depressing, shocking and revolting.

For me, one such time came when Faust mentioned that many Union graves were vandalized in the South. Another was the realization that, on some battlefields, bodies were left unburied to rot or even worse.

Indeed, one federal officer, given the job after the war to get the Union bodies buried in cemeteries, found at Shiloh human bones in “large quantities.” And he learned something else from nearby inhabitants.

Faust writes that the officer was told by those people “that their hogs, customarily left free to forage, were no longer fit to be eaten ‘on account of their living off the dead.’ ”

Patrick T. Reardon

1.5.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.