On September 9, 2017, I wandered over to Westminster Abbey because I was in London for the first time seeing the sights and I knew it was chockful of a lot of historical stuff.

When I got inside, it was a magical place.

For one thing, this structure — at least in parts of it — is nearly 1,000 years old. There are spots on its floor where Queen Victoria stood, walls and wood that William Shakespeare could have touched. It’s even depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry from 1066. I’ve lived all my life in Chicago which is not yet 200 years old.

For another, the interior of the abbey is a wonderfully chaotic mix of altars, windows, monuments, graves, memorials and, here and here, over-the-top sculptures. And this mess of stuff — a building in which more than 3,000 people are buried and hundreds of others memorialized — contained, in its tumult, a vibrant, idiosyncratic history of the English peoples.

For a third, it contains the grave of Elizabeth I, and I’m a big fan of her and her time — a feminist powerhouse before there was feminism.

Finally, the abbey was, for me, a magical place because that afternoon at 3 p.m. Evensong was held. I found this out when I came in and hung around, waiting near the ropes, so I could be sure to get a seat for the prayer — daily prayer has been offered in this place for more than ten centuries — at which the abbey choir would sing.

I was among the first dozen or so people, and we ended up sitting in the choir stalls on either side of singers. It was transcendent.

Unique to each reader

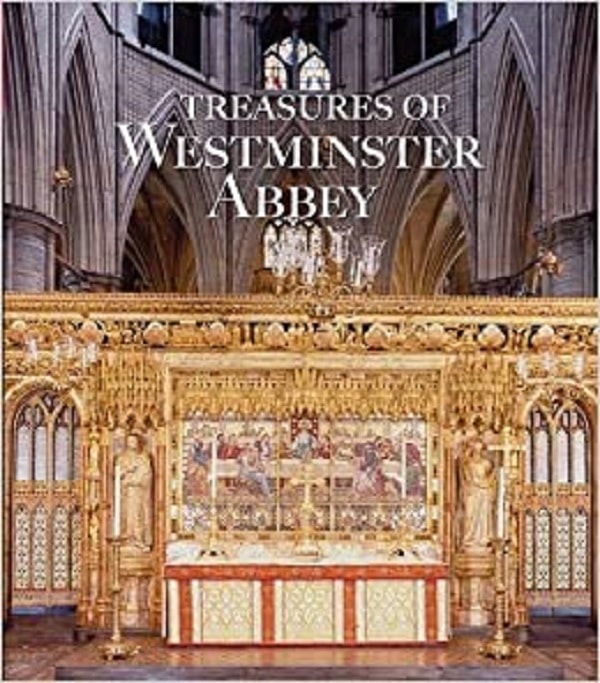

Treasures of Westminster Abbey by Tony Trowles, published by Scala Arts & Heritage is a beautifully illustrated 176-page celebration of the abbey. Because of its large format — roughly 10 inches by 11 inches — it’s not exactly a guidebook. It would be a clumsy item to carry around with you while touring the abbey.

It is a guide, though, inasmuch as it gives the reader a bit of information about the various sections of the structure (including maps), about the abbey’s history, about its stained glass windows and other church-related art and about hundreds of the people who are buried within its walls or memorialized.

You can look through the book after a visit as a reminder of what you saw. Even more, though, this is a book to study ahead of time — to get a feel for the layout and to make notes of graves or other aspects of the abbey that you want to be sure to see.

In that way, it’s very much a book that’s different with each reader — unique, in fact, since each person will bring personal interests and goals to the reading of the work.

My list

My own reading of Treasures, fueled with my hope and expectation of visiting again the Abbey, became a checklist of what I want to make sure to see or, in some cases, see again on a return visit.

Here’s the list:

- Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), government bureaucrat and the author of The Canterbury Tales

- Henry V (1387-1422), subject of four of Shakespeare plays and winner at the Battle of Agincourt, recalled with an effigy of black oak atop his marble tomb.

- William Tyndale (1494-1536), the Bible translator, memorialized with a marble and alabaster tablet since, alas, he was burned at the stake as a heretic in the Netherlands.

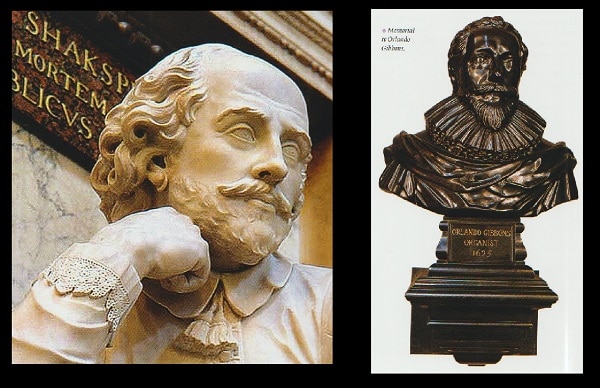

- William Shakespeare (1564-1616), memorialized with a sculpture and marble monument since he is buried at Stratford-upon-Avon. (See photo below)

- Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), English composer and organist at the Abbey, memorialized with a black marble bust, a copy of the one on his monument at Canterbury Cathedral where he is buried. (See photo below)

- Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), Lord Protector from 1653, memorialized with a stone tablet that shows where his mortal remains were buried for a few years after his death before his body was disinterred during the Restoration of the monarchy, hung from a gibbet at Tyburn and then beheaded.

- Aphra Behn (1640-1689), the first English female professional writer, long-overlooked but later championed by Virginia Woolf who wrote “all women together ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn” — in the Abbey.

- George Frederick Handel (1685-1759), recalled with a stunning life-size sculpture of the composer at the organ with a page of easily read music in his hand, above where his grave is marked in the floor. (See photo below)

- David Garrick (1717-1779), honored with a vividly theatrical life-size marble statue of the dramatist that shows him pushing aside the curtains of a small stage. (See photo below)

- Jane Austen (1775-1817), the novelist who wrote Emma and Pride and Prejudice is memorialized with a tablet and buried and Westminster Cathedral.

- Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1963), the British prime minister in World War II is honored with a memorial stone of green Italian marble and buried in Oxfordshire.

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), the American President, buried at Hyde Park in New York, is recalled in a tablet erected by the British government in 1948 as “a faithful friend of freedom and of Britain.”

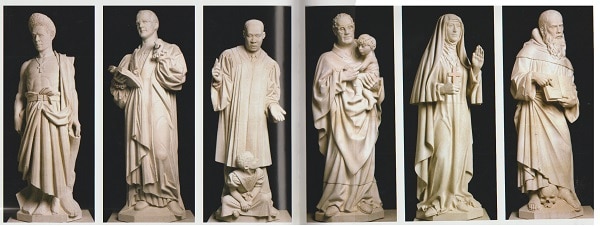

- Ten Martyrs of the 20th Century, a range of religious and spiritual leaders, including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dietrich Bonhoeffer and St. Oscar Romero, honored with life-size statues installed in 1998 in niches above the west door, the main entrance to the abbey. (See photo below)

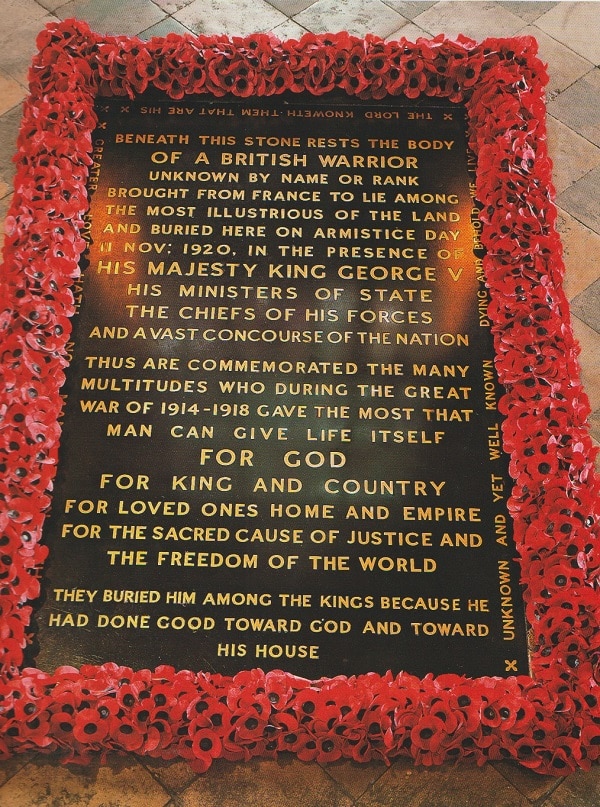

- Unknown warrior, an unidentified British serviceman killed during World War I, buried in 1920 in a grave marked with a large stone of black marble and an inscription in brass letters. (see photo below)

The photos

William Shakespeare and Orlando Gibbons

George Frederick Handel and David Garrick

Unknown warrior

20th century martyrs

Three other photos

Reading the Treasures book, I found two items I missed in my 2017 visit that I’ll want to see in my next visit:

A portrait of Richard II, dating from around 1400, is on a wooden panel that hangs on a pillar outside St. George’s Chapel and is the earliest known contemporary painting of an English monarch.

And, even older, the Coronation Chair, fashioned in the late 1200s in Scotland and used by British monarchs since 1300.

In addition, there is one item I look forward to seeing again in the out-of-the-way Chapter House part of the Abbey: the oldest door in Britain, dating from about 1050, and, according to some scholars, it may have been a major door in the abbey used by King Edward the Confessor.

Elizabeth I (and her sister)

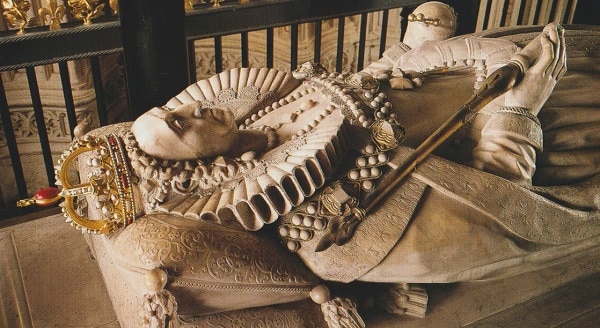

Ultimately, though, for me, the jewel in the Abbey’s crown of treasures is the tomb of Elizabeth I (1533-1603), one of two daughters of Henry VIII.

Her mother, Anne Boleyn, was beheaded for treason when Elizabeth was three years old. Later, Elizabeth’s Catholic sister Mary I (1516-1558) sent her to the Tower of London. When the barge carrying the Protestant Princess to what she feared would be her death arrived at the Traitors Gate — the same entrance through which her mother was brought — the 21-year-old refused to step onto land, fervidly proclaiming her innocence.

Tested and steeled by the threats that overhung her childhood and young womanhood, Elizabeth at 25 took over the reins of government, and, surrounded by a horde of men, some well-meaning, some treacherous, she led the nation for nearly half a century.

When, in 1588, the Spanish Armada was threatening the British Isles, Elizabeth, wearing a silver breastplate over a white velvet dress, addressed her troops at Tilbury in Essex. She told them:

“My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourself to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people …

“I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.”

Ah, what a woman!

And, in one of the most final of final words, inside Elizabeth’s large, ornate marble monument, her coffin rests atop the coffin of Mary I.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.21.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.