Over the past eight years, since April, 2016, I’ve been working my blissful way through Terry Pratchett’s 41 Discworld novels, starting with the first one, The Color of Magic — Wait, I tell a lie, I started with a graphic novel version of the first two, The Color of Magic and The Light Fantastic.

Pratchett died at the age of 66 in March, 2015, and the last of his Discworld books, The Shepherd’s Crown, was published at the end of that summer. I’d read it right away — and then what?

At this point, I can’t remember if I’d already read every one of the Discworld novels, but I know however many there were, I’d read them in a scattershot manner that led me to miss things here and there and misunderstand others. So, starting at the beginning enabled me to see each book in its context, knowing what had gone before (while also, without perfect memory, having a sense of what was to come).

It was a way to honor Pratchett — and also feed my hunger for his writing. And it’s been, as I say, a blissful journey, reading four or five of the books each year.

Now, the 37th Discworld book

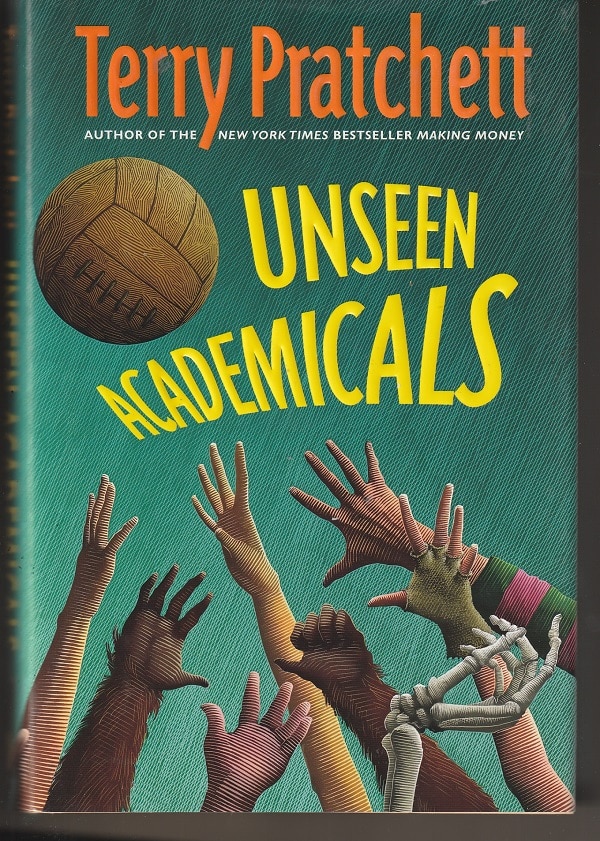

Now, I’ve reached Unseen Academicals, his 37th Discworld book — and the first published after he announced his Alzheimer’s diagnosis in December, 2007.

Pratchett’s announcement came three months after he’d sent Making Money out into the world, and Unseen Academicals didn’t arrive until two years later.

That was a long wait for fans who were used to getting a new book every year. In addition to the delay, Unseen Academicals, published in the fall of 2009, was different because it was, at 400 pages, the longest Discworld book by far, about 25 percent longer than the next longest.

The question, of course, was whether the new Discworld would be as good as all the earlier ones or if it would show the damage of Pratchett’s disease.

I don’t remember noticing any diminution of his storytelling when I read Unseen Academicals the first time.

I am aware now, having re-read the book, that there were elements of the novel that I didn’t get because of my disorganized reading of the earlier books. These were elements that I saw much more clearly on my re-reading of the book.

The City Watch as a running joke

And I have to say that, after re-reading the book, I didn’t notice any new weakness in Pratchett’s ability to tell his story with humor, zest and cleverness.

But I did notice some differences, and I think they had to do with his Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Unseen Academicals seemed much darker to me, this time around. Such as in Pratchett’s portrayal of the City Watch who, up to this point, had been something of a running joke throughout the Discworld novels.

There are some really odd and goofy characters in the Watch, and even some of the more normal members aren’t all that normal, for instance, a werewolf and a 6’6” dwarf — and they’re dating (in a very cute way).

Sam Vimes is the ex-drunk who is not only the head of the City Watch but also, by reason of his marriage to Lady Sybil, a Duke, but still a street cop at heart. His huge anger is kept in check only by his even more gargantuan belief in law, order and justice.

The Watch, in other words, were a lot of fun through the first thirty-six books. But not in Unseen Academicals.

“Big, big sticks”

Late in the novel, Trevor Likely, a kind of Romeo to the novel’s Juliet (who is surprisingly called Juliet), is talking about all the bad things that could go wrong at a planned football game.

It is a game will pit a team from the wizards’ Unseen University (called the Unseen Academicals) against a team of local people that is going to be dominated by thugs, goons and hooligans. It has been arranged, for mysterious reasons, by the tyrant of Anhk-Morpork, the Patrician, Havelock Vetinari, but that doesn’t calm Trevor’s qualms.

“Vetinari’s got the Watch, though, ‘asn’t he? And you know about the Watch. Okay, so there’s some decent bastards among ‘em when you get ‘em by theirselves, but if it all goes wahoonie-shaped they’ve got big, big sticks and big, big trolls and they’ve not got to bother too much about who they hit because they’re the Watch, which means it’s all legal.

“And, if you get ‘em really pissed off, they’ll add a charge of damaging their truncheons with your face.”

One benefit for me of having read the earlier books in order is that none of them depict the City Watch as such law enforcement storm troopers. Early on, the books described the Watch personnel as silly, for the most part, and later as good guys trying to do the right thing.

In Unseen Academicals, however, Pratchett portrays them as indiscriminately violent and unreasoning. They come across, in my reading, as the blind destructive force of a blind destructive Fate that has no truck with any idea of fairness.

Perhaps that’s how one feels to hear a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Stupid and mean and evil

There is also a strong strain of bitterness in Unseen Academicals.

The central character is Mr. Nutt who has read just about everything to try to figure out how to be of “worth” and who speaks with the clarity and precision of someone who has read just about everything and who, for the first seven years of his life, was chained to an anvil. There is a darkness to his biography, hidden from those around him.

Mr. Nutt is a small, seemingly harmless young man who works at the Unseen University and is close friends with Trevor Lively. It turns out that he is one of the last living descendants of a kind of creature that, in human myths, was an extremely violent and destructive weapon of war — a weapon that was created, i.e., crossbred, by humans for violence and destruction.

Despite that family legacy, Mr. Nutt is quiet and inoffensive and yearning for “worth,” but is still badgered by the bullies of the world. In Unseen Academicals, the bullies come across as particularly stupid and mean and evil.

“Mother and children”

And the Patrician tells this story:

“I have told this to few people, gentlemen, and I suspect never will again, but one day when I was a young boy on holiday in Uberwald I was walking along the bank of a stream when I saw a mother otter with her cubs.

“A very endearing sight, I’m sure you will agree, and even as I watched, the mother otter dived into the water and came up with a plumb salmon, which she subdued and dragged on to a half-submerged log. As she ate it, while of course it was still alive, the body split and I remember to this day the baby otters who scrambled over themselves to feed on the delicacy.

“One of nature’s wonders, gentlemen; mother and children dining on mother and children.

“And that’s when I first learned about evil. It is built in to the very nature of the universe. Every world spins in pain.”

Perhaps that’s what you end up writing after hearing a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

“Can’t magic them sensible”

And one of the wizards, Ponder Stibbons, is asked to work some magic to avoid the violence and destruction that is certain to break out in the game between the Unseen Academicals and the local team of thugs.

And he explains:

“We can do practically anything, but we can’t change people’s minds. We can’t magic them sensible. Believe me, if it were possible to do that, we would have done it a long time ago.

“We can stop people fighting by magic and then what do we do? We have to go on using magic to stop them fighting. We have to go on using magic to stop them from being stupid. And where does it all end?”

Nothing comes through Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books — and all of his writing — more than his deep affection for human beings, an affection that understands the ability of humans to be joyful, courageous and clever and the ability of humans to be close-minded, grumpy and, well, Ponder says it well, stupid.

Throughout the Discworld books, Pratchett celebrates humanity for all its beauty and warts, but, in Unseen Academicals, he seems more aware of the warts, seems even weighed down by the reality of those warts — weighed down by the fact that many people use their lives for meanness and fear.

Weighed down by his knowledge that his time as a human being is suddenly very short and he doesn’t want to waste it whereas many humans will continue to go blindly along after he’s gone in their meanness, fear and stupidity.

Perhaps that’s what one ends up thinking about after hearing a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.30.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.