There is a beautiful embrace of complexity, a wonderful delight in ambiguity and amazements, to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s 2007 book of history, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History.

It is the book of a historian about the history of women that rejoices in details and eschews broad-brush statements.

The stories of famous women, Ulrich notes, have routinely been “appropriated for contradictory causes.” For instance, Queen Esther, the Biblical protector of the Jewish people, has been used as a model of political action and of political silence — of revolt and of submission.

That’s why details matter….Details help us understand the precise circumstances that allowed Artemisia Gentileschi to become an artist, or Harriet Jacobs a writer. Details keep us from falling into the twin snares of “victim” history” and “hero history.” Details let us out of boxes created by slogans.

This last sentence comes near the very end of Ulrich’s book, and it suggests why she came to write it.

“Well-behaved women”

Back in 1976, in her first scholarly paper, Ulrich was reporting on her research of 17th century New England women who were unknown except for being the subjects of funeral sermons highlighting their piety.

In her first paragraph, she noted that Cotton Mather referred to these women as “the hidden ones” and that they spent their time living quietly and virtuously, giving no speeches, attending no colleges, casting no votes. And she ended the paragraph this way:

Hoping for an eternal crown, they never asked to be remembered on earth. And they haven’t been. Well-behaved women seldom make history.

That final sentence was a writerly grace note for Ulrich, one that provided a context for the women who were her subjects and one that acted as a quick and passing commentary on the wider subject of history.

Then, nearly two decades later, journalist and author Kay Mills published a popular history of American woman, From Pocahontas to Power Suits: Everything You Need to Know About Women’s History in America, and, for the book’s epigraph, she used Ulrich’s sentence with a slight word change: “Well-behaved women rarely make history.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

“A grainy photo”

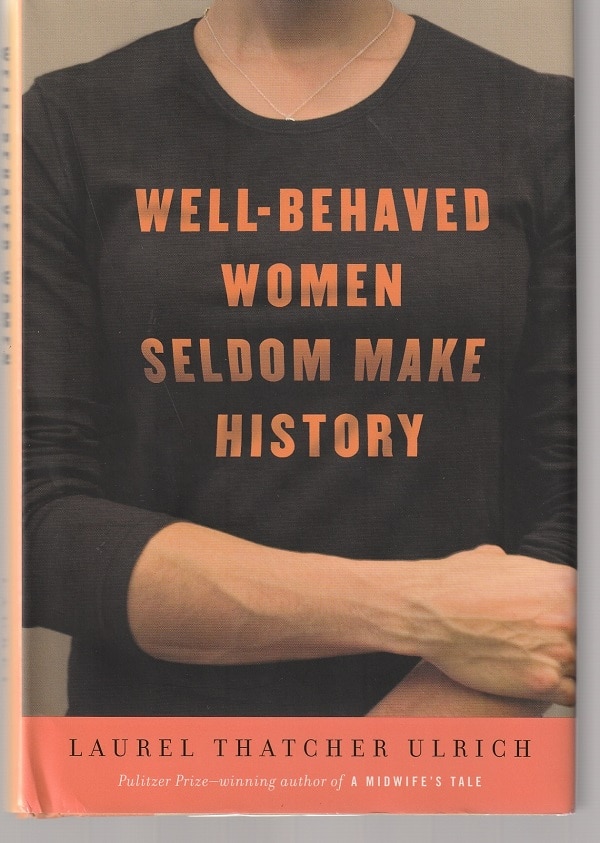

Ulrich’s sentence, in various iterations, became a slogan that ended up on coffee cups and bumper stickers, T-shirts and greeting cards, tote bags and magnets. And Ulrich found that, all of a sudden, she had “this curious fame.”

In a 22-page introduction, titled “The Slogan,” she details many of the ways that the phrase has been used to endorse a wide variety of activities and thinking, and she makes clear that this has been more than a bit unsettling for her.

At a checkout counter of one independent bookstore, Ulrich found her name and sentence on “a dusky blue magnet embellished with one leopard-print stiletto-heeled shoe above a smoldering cigarette in a long black holder.” And then there was a website selling T-shirts that featured both her name and a grainy photo of her at a lectern.

When I e-mailed to ask why the proprietors were selling my picture without permission, they responded:

“I guess we are not very well-behaved girls.”

“The right to make history”

Ulrich writes that the ambiguity of the sentence is certainly the reason for its wide use.

To the public-spirited, it is a provocation to action, a less pedantic way of saying that if you want to make a difference in the world, you can’t worry too much about what people think. To a few it may say, “Good girls get no credit.” To a lot more, “Bad girls have more fun.”…

And because I am a historian, I can’t quite leave it at that. For some time now I’ve been collecting responses to the slogan, puzzling over the contradictory answers I have received, and wondering why misbehavior is such an appealing theme….One thing it doesn’t appear to have a lot to do with history, at least not the kind that comes in books.

Ulrich spends part of this introduction discussing how famous women, such as Rosa Parks and Joan of Arc and Lady Godiva, Marie Curie and the Angolan heroine Njinga Mbandi, can be seen — and have been seen — as well-behaved and not well-behaved.

And she spends part discussing her career as a historian, explaining that, when she wrote that “well-behaved women seldom make history,” she was making a commitment to help recover the lives of the otherwise obscure women who were her subjects.

It was a commitment that she has lived out as a historian, publishing such books as the Pulitzer Prize-winning A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard based on her diary, 1785–1812 (1990) and A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (2017).

The extensive popularity of that early sentence and the many ways in which it has been used has surprised her. And, yet, she notes:

While I like some of the uses of the slogan more than others, I wouldn’t call it back even if I could. I applaud the fact that so many people — students, teachers, quilters, nurses, newspaper columnists, old ladies in nursing homes, and mayors of western towns — think they have the right to make history.

“Reading against the grain”

Anyone coming to Well-Behaved Women looking for a screed about how women have been oppressed throughout history or hoping for a paean to the power of overlooked heroines will be disappointed.

In looking at women in human history, Ulrich looks at the details, and the result is a complex examination of limits and opportunities, of success and failure.

For instance, her opening chapter tells the story of three writers:

- Christine de Pizan (1364 – c.1430), the author of The City of Ladies which gathered and told the lives of worthy women from story and history, an early effort to understand women in the arc of human existence.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), the radical women’s rights activist and author of Eighty Years and More, a memoir that Ulrich describes as “not a history that included women, but it did honor rebellion, the dominant theme in her life story…the making of a revolutionary.”

- Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), a major 20th-century novelist and feminist icon whose books included A Room of One’s Own in which she fantasized about what Shakespeare’s life would have been if he’d been a girl — imagining a sister of his, Judith, who isn’t permitted to go to school, runs away to be an actor in London, is laughed out the door, becomes pregnant and commits suicide.

These three, Ulrich writes, used history “to argue against narrow definitions of womanhood,” doing so “by reading against the grain of existing narratives and by writing new ones of their own.”

“History is made in libraries”

Throughout Well-Behaved Women, Ulrich uses these three writers as touchstones but doesn’t treat them as infallible.

Consider that, over the course of ten pages, Ulrich details the lives of three gifted women from Shakespeare’s time — painter Artemisia Gentileschi and writers Elizabeth Cary and Aemilia Lanyer. All three had talent and pluck and were blessed with fathers who furthered their careers and were willing to permit them to seek needed training in circumstances where they had to live by their wits.

They succeeded, despite difficulties, and left a record of their lives and their work. Yet, Woolf, a feminist icon writing in 1929, couldn’t imagine a talented woman succeeding as an artist in Shakespeare’s world. As Ulrich writes, “Why was it, she asked, that ‘no woman wrote a word of that extraordinary literature when every other man, it seemed, was capable of song or sonnet’? ”

That’s what Woolf was asking a century ago, but Ulrich notes the questions are different today:

Why was it that Woolf knew nothing about the women writers who were contemporaries of Shakespeare? Why did Professor Trevelyan dismiss women’s lives with a few grim sentences? The records were there, but no one had bothered to look.

Woolf’s fable is a reminder of a central theme of this book: that history is made in libraries as well as in streets. Because Woolf went looking for forgotten women, others eventually joined the search.

“No universal sisterhood”

That search for women in history is the aim of Ulrich’s book, and she tells many complex stories, wonderfully textured with the grit and friction of life.

Serious history reminds us that women have been on both sides of most revolutions. There is no universal sisterhood, no single history of women. Women were among the accusers as well as the victims in European witch hunts. They supported as well as worked against slavery.

Part of the history of women is what women have done. Part of it is how men have viewed women and fit them into history or didn’t. Part, too, is whether anyone is looking and asking questions — with an open mind.

If history is to enlarge our understanding of human experience, it must include stories that dismay as well as inspire. It must also include the lives of those whose presumed good behavior prevents us from taking them seriously.

If well-behaved women seldom make history, it is not only because gender norms have constrained the range of female activity but because history hasn’t been very good at capturing the lives of those whose contributions have been local and domestic.

The bottom line for Ulrich is that history isn’t as simple as well-behaved and not well-behaved. It’s about who gets noticed and why. As she writes in her final sentence:

Well-behaved women make history when they do the unexpected, when they create and preserve records, and when later generations care.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.3.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.