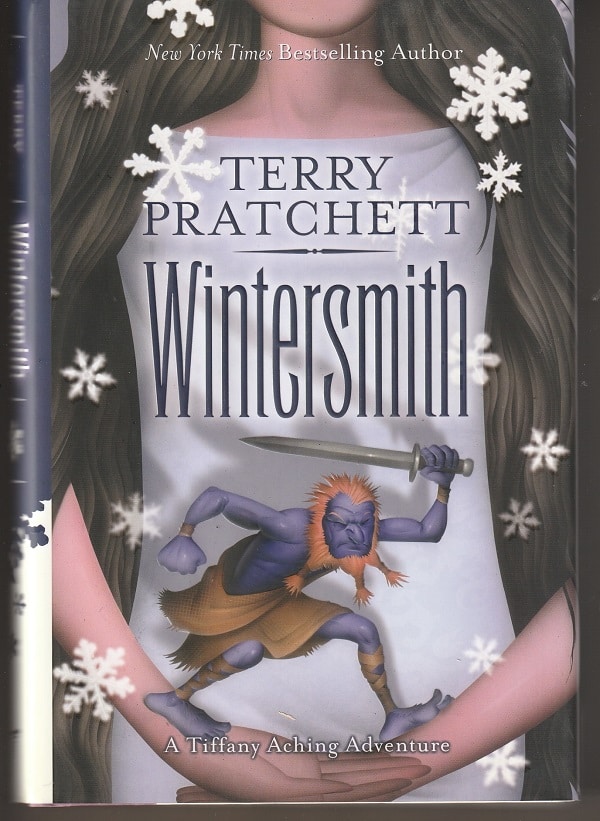

In Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, the Nac Mac Feegles are six-inch-tall, red-haired, blue-skinned fairies who — nearly all of them male — drink, fight, steal and swear in something like a Scots accent and are a perpetual after-game Manchester United fandom without the football.

Yet, they are kind-hearted, totally courageous (since they are technically already dead), do a lot of good for those they like — such as the “wee big hag” Tiffany Aching, a witch in training, nearly 13 years old — and provide instant comic relief in the seven Discworld novels in which they appear. Here’s how they show up in Wintersmith:

A small group of little men was creeping across the floor. Their skins were blue and covered with tattoos and dirt. They all wore very grubby kilts, and each one had a sword, as big as he was, strapped to his back. And they all had red hair, a real orange-red, with scruffy pigtails.

One of them wore a rabbit skull as a helmet. It would have been more scary if it hadn’t kept sliding over his eyes.

The Feegles are all over the place in Wintersmith, Pratchett’s 2006 novel in which Tiffany, due to high spirits, finds herself dancing with the spirit of winter, the Wintersmith, in a Dark Morris dance.

That’s a ritual in which the Wintersmith and Lady Summer — two elementals, i.e., powerful beings without the personalities or egos of gods and goddesses — transfer power, winter taking ascendence as summer descends to wait in the deep soil for the next season turn.

“Really a metaphor”

Tiffany’s PWOL (present without leave) in the dance sets in motion a number of plots — some of which involve witches being witches, others of which have to do with Wintersmith’s attempt to become human to meet Tiffany and make her his queen, and still others about the threat of an unbroken winter which has the bright side, if you’re really askew, of eliminating death because it will kill every living thing so no other beings in the future will have to die.

The Feegles have been told they are going to have to go (again) to the Underworld (to the great distraction Death, the guy with the huge scythe) and bring along a relatively unheroic Hero in the form of Roland, the young boy once saved by Tiffany who may or may not be sweet on her (as she may or may not be sweet on him).

They tell Roland that they’ll lead him to the limbo-like shadow depths where he will save a lady in distress, and he says:

“Oh, you mean like Orpheo rescuing Euniphone from the Underworld? It’s a myth from Ephebe. It’s supposed to be a love story, but it’s really a metaphor for the annual return of summer.”

To which the Feegles stare in stunned uncomprehending silence.

“A lie to help people”

To which, one of the Feegles, Awfully Wee Billy Bigchin, a gonnagle — i.e., a bard and mousepipe player who, unlike most of the others, can read and write and is a storyteller and tends to be a brighter bulb in the Feegle billboard — explains:

“A metaphor is a kind o’ lie to help people understand what’s true.”

That sentence brought me to a full-stop as I was reading Wintersmith because it sums up all of Pratchett’s writing. His 41 Discworld novels as well as his other fictions are all “lies to help people understand what’s true.” (Of course, that’s what all great fiction is about.)

There is wild silliness in his books, a lot of slapstick, a lot of puns. The novels are droll. They are witty and clever and goofy. And they are serious.

Pratchett didn’t write nonsense. He wrote stuff that, at times, seemed like nonsense because life for human beings is often and in many ways nonsensical.

His stories are metaphors for life. His characters are metaphors for us and for the complicated craziness that any human being has to face and find a way to maneuver through, around or away from.

His comedy is a metaphor for the tragedy of living. Human beings are born to die, and the only way to handle it is to roll with the punches that life throws until the final one comes — and the best way to roll with the punches is through laughter.

“Something to live up to”

At one point about two-thirds through Wintersmith, Tiffany is staying with a veteran witch named Nanny Ogg who, like all witches, serves the people of her neighborhood as a medicine woman, midwife, adjudicator and whomever they need her to be.

Unlike wizardry, witchcraft has less to do with magic and more to do with hard common sense and general availability.

Nanny took her to the isolated village of Slice, where people were always glad and surprised to see someone they weren’t related to. Nanny Ogg ambled from cottage to cottage along the paths cut in the snow, drinking enough cups of tea to float an elephant and doing witchcraft in small ways.

Mostly it seemed to just consist of gossip, but once you got the hang of it, you could hear the magic happening. Nanny changed the way people thought, even if it was only for a few minutes. She left people thinking they were slightly better people. They weren’t, but as Nancy said, it gave them something to live up to.

This goes to the heart of Pratchett’s universe — that metaphorical place where human-like lives are lived out through a comic and serious storytelling.

Pratchett always opts for the everyday people. He knows their faults, but also knows their good points. He knows that, for them, the difference between having a good day and a bad day is simple — hope.

That’s what, in this tiny moment in Pratchett’s world, Nanny gives to the people of Slice. She gives them a reason to hope and to strive maybe to be “slightly better people.”

“Silly unthinking insults”

It’s also why Pratchett gets so mad at those human beings who, knowingly, take advantage of the blindnesses of people in a ruthless, merciless way.

And, yet, he can also make the reader resonate with the humanity of a villain.

In Wintersmith, Annagramma Hawkin is another witch in training who, unlike Tiffany, is arrogant, bossy and hoity-toity. And she is making a total failure of her first posting as a full-fledged witch.

She asks Tiffany for help while also trying to make it seem that Tiffany is coming to her for lessons. She’s clueless about how people live and how they think and feel, and, well,….

There were times you [ i.e., Tiffany] could feel that the world would be a better place if Annagramma got the occasional slap around the ear. The silly unthinking insults, her huge lack of interest in anyone other than herself, the way she treated everyone as if they were slightly deaf and a bit stupid…it could make your blood boil.

Talk about a villain in Pratchett’s fictional universe. She is everything a witch shouldn’t be. Everything a human being shouldn’t be.

“This worried, frantic little face”

And yet…

But you put up with it because every once in a while you saw through it all. Inside there was this worried, frantic little face watching the world like a bunny watching a fox, and screaming at it in the hope that it would go away and not hurt her.

This is a core Pratchett realization: Even bad guys have feelings. Even bad guys are confused and anxious and unsure of their place in the world.

Some bad guys can do better. Annagramma does. By the end of Wintersmith, she is on her way to being a decent, helpful witch.

Even bad guys are people. That’s a constant lesson in Pratchett’s books.

Annagramma, like all his other characters, is a metaphor. For you and me.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.13.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.