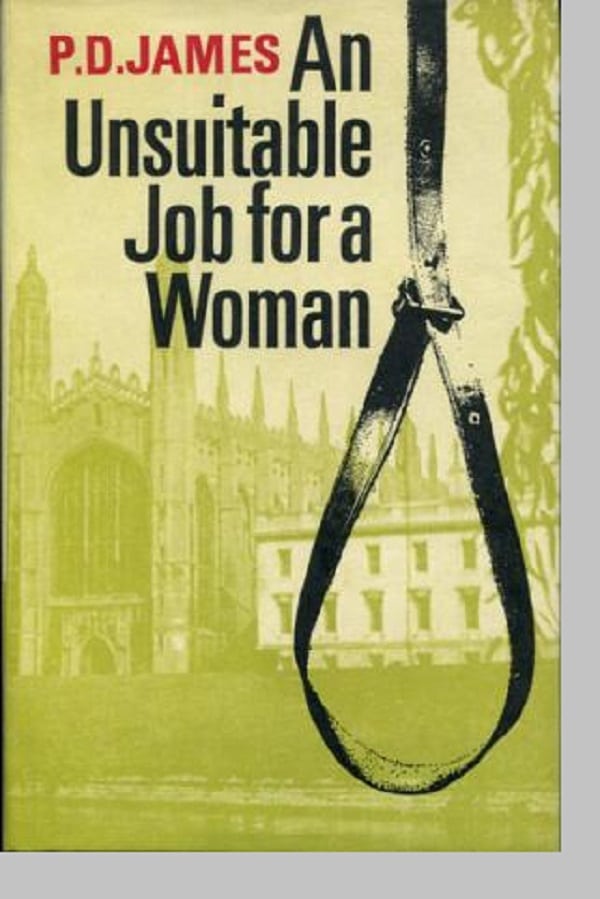

In 1972, when P.D. James published An Unsuitable Job for a Woman, she’d been a novelist for just a decade.

Her first four books were centered on Adam Dalgleish, a tightly constrained, deep-feeling police detective who is also a modestly well-known poet — Cover Her Face (1962), A Mind to Murder (1963), Unnatural Causes (1967) and A Shroud for a Nightingale (1971).

In Unsuitable Job, her fifth novel, James was experimenting with a different central character, Cordelia Gray, a beautiful, slight and tough 22-year-old whose life has been shaped and misshaped by experiences ranging from a poet-revolutionary father to six years in a convent school, from the art museums of Europe to loud, crowded lower-class foster homes, from her mother’s death after giving her life to the poignantly inept ex-cop Bernie Pryde who took a shine to her and made her a partner in his private detective agency.

Dalgleish, though, isn’t far away.

Dalgleish

Throughout the novel, Cordelia is reminded of the many repeated adages that Bernie passed on to her as pronunciations from on high, i.e., the savvy insights of his former boss, Dalgleish. From her irritation at the repetitions and her affection for Bernie, she envisions Dalgleish, who bounced Bernie out of police service, as something of a prig.

Then, at the novel’s end, Dalgleish makes a very definite appearance, and, as Cordelia sits across from him in his office, with a policewoman sergeant taking notes, James describes her thinking:

He was old of course, over forty at least but not as old as she had expected. He was dark, very tall and loose-limbed where she had expected him to be fair, thick set and stocky. He was serious and spoke to her as if she were a responsible adult, not avuncular and condescending. His face was sensitive without being weak and she liked his hands and his voice and the way she could see the structure of his bones under the skin.

He is attractive as a man and as a personality, but, at this moment in Cordelia’s life, he’s dangerous.

In the end, he comes away, telling a colleague:

“I don’t think that young woman deludes herself about anything.”

Convolutions

That comment — “He was old of course, over forty at least” — is the voice of the young. And part of the pleasure of Unsuitable Job, written when James was 52, is how well she captures a moment in history when young people of the West, Baby Boomers all, were beginning to understand that they held huge power in society.

Not only Cordelia, but four other people of 22 or so (my own age in 1972), Cambridge University students, blasé about sexual freedom, quick to apply the label fascist to a rich man, unworried or burdened by student loans or future expectations, blithe, breezy, insubstantial — and all friends of Mark Callender, who is found hanged in an old farm cottage.

There are goodly number of suicides — or apparent suicides — in Unsuitable Job. Even, as the novel opens, that of Bernie Pryde, recipient of a dire cancer diagnosis, whose body is found by Cordelia in his office with his wrist slashed.

There are also at least a couple murders and several other deaths, including that of a small boy and that of a dark, lurking sociopath and that of a cold-hearted bastard, as well as Cordelia’s mother and, just before the start of the novel, her father.

As with her earlier novels, James, I think, is still throwing too many ingredients into her stew, although they’re all pretty tasty. Unsuitable Job is a good novel, but it could have been a lot better without some of the convolutions.

As with her earlier novels, James, I think, is still throwing too many ingredients into her stew, although they’re all pretty tasty. Unsuitable Job is a good novel, but it could have been a lot better without some of the convolutions.

“Morbid excrescences”

When I say convolutions, I’m not including the lengthy descriptions that James provides the reader in delightfully well-observed prose — descriptions of people, such as the one above of Dalgleish, and of places, such as this room into which Cordelia is led:

It was a horrible room, ill-proportioned, bookless, furnished not in poor taste but in no taste at all. A huge sofa of repellant design and two armchairs surrounded the fireplace and a heavy mahogany table, ornately carved and lurching on its pedestal, occupied the center of the room.

Cordelia’s reactions to many of the places she sees tend to be critical, such as one ugly Victorian house:

The garden suited the house; it was formal to the point of artificiality and too well-kept. Even the rock plants burgeoned like morbid excrescences at carefully planned intervals between the terrace paving stones. There were two rectangular beds in the lawn, each planted with red rose trees and edged with alternate bands of lobelia and alyssum. They looked like a patriotic display in a public park. Cordelia felt the lack of a flag pole.

“Perpetually ready”

These descriptions from Cordelia’s point of view are always pungent and keen, but, just as the constant negativity was beginning to grate on me, James offered an explanation.

Cordelia is about to enter one of the Cambridge University buildings, a structure she judges too pretty for its purpose. Then, James notes:

She concentrated on her criticism of the building; it helped to prevent her being intimidated.

Like the seemingly throwaway facts about Cordelia’s past that James drops into her story, this insight explains much about how the young woman approached the world.

In a similar way, there is this glimpse into who Cordelia is. It occurs as she is preparing to go to Cambridge to begin investigating the hanging of Mark Callender.

Cordelia enjoyed clothes, enjoyed planning and buying them, a pleasure circumscribed less by poverty than by her obsessive need to be able to pack the whole of her wardrobe into one medium sized suitcase like a refugee perpetually ready for flight.

“Such agony”

The best of the descriptions that James provides the reader in Unsuitable Job — and one of the best in all of her work — doesn’t have to do with a place or a person, but an insect.

Cordelia and some other young people have built a fire.

As she bent forward to stir the coffee Cordelia saw a small beetle scurrying in desperate haste along the ridges of one of the small logs. She picked up a twig from the kindling still in the hearth and held it out as a way to escape. But it confused the beetle still more. It turned in panic and raced back towards the flame, then doubled in its tracks and fell finally into a split in the wood. Cordelia pictured its fall into black burning darkness and wondered whether it briefly comprehended its dreadful end. Putting a match to a fire was such a trivial act to cause such agony, such terror.

In that paragraph, P.D. James expresses the worldview at the heart of all her writing and sums up all of human existence and all of existence in six short sentences.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.17.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.