Early in her writing career, critics often chided P. D. James for what they said were slow-moving plots in her mysteries. In a way, they were right, but they missed the point.

Any readers who came to a P.D. James novel looking for fast action — or, indeed, much action at all — were going to be disappointed. On occasion, Commander Adam Dalgliesh of Scotland Yard would hasten to stop a crime or nab a suspect, but such derring-do would take up very few pages of a James novel.

There’s one moment in Death of an Expert Witness when, in the dark of an East Anglia night, Dalgliesh and Inspector John Massingham drive quickly from Hoggatt’s forensic science laboratory to the nearby Wren Chapel after the chapel’s bells unaccountably begin ringing. Their dash to investigate takes up a single page and doesn’t result in a shoot-out, just a grisly discovery.

Indeed, the book ends with Dalgliesh quietly walking with the killer around a garbage-strewn waste area of no man’s land, calmly discussing death and dying.

That sort of quiet, weighted scene is the core of a P.D. James novel, not a lot of clickety-clack of the plot.

“Done the same”

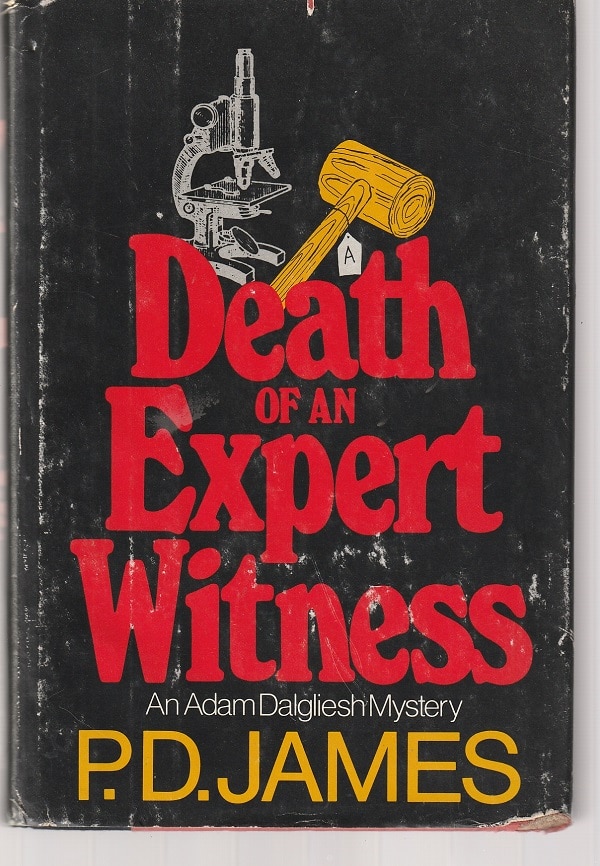

Published in 1977, Death of an Expert Witness was the sixth of 14 Adam Dalgliesh novels by James. The first Cover Her Face was published in 1962, and it took James a while to find firm footing in the genre.

She was a fervent admirer of Jane Austen (as she showed when she borrowed Austen’s Pride and Prejudice world for her 2011 novel Death Comes to Pemberley). And, like Austen, James was wanting to write literature, work that was primarily interested in what makes people tick, their emotions, their experiences, their blind spots.

Not for her, the black and white world of much crime fiction — good guys and bad guys.

Dalgliesh isn’t your normal know-it-all crime-solver. He’s a poet and a thoughtful man who, in the midst of his day, in the midst of his job, is always studying his internal workings, aware of his flaws and idiosyncrasies. For instance, near the end of Death of an Expert Witness, he confronts a woman who has had affairs with more than one of the murder suspects and is astonished by her reaction.

But it was his own self-knowledge that disgusted him more. He understood only too well what had driven [those men] to creep guiltily like randy schoolboys to that rendezvous, to make themselves partners in her erotic, esoteric game. Given the opportunity, he would, he thought bitterly, have done the same.

Embracing complexity

There is, it must be said, a lot of lust taking place behind the scenes in Death of an Expert Witness, and, in the hands of another writer, the novel could have been quite prurient.

By the same token, there is also much anger and deep anxiety and isolation and sorrow and uncertainty. Given full rein, all those many emotions would have resulted in a cacophonous story of screams, screeches and moans.

James, though, looks at all of this with a cool, knowing — maybe impartial, maybe not — gaze. She gives the sense that these characters in her novel are like herself and her readers, each a ball of contradictions and urges, of good intentions and bad habits.

This is why her books will seem slow-moving to fans of many other writers in the genre. James eschews the superficial, the stereotypical. She embraces complexity in virtually every character.

“Thin whisper of breath”

Indeed, in the 62 pages of the first section of Death of an Expert Witness, James introduces the reader to the inner thoughts and psychologies of more than a dozen characters, many of who will become murder suspects — and they aren’t even the full roster of significant people in the novel.

For instance, three-year-old William, the son of Henry Kerrison, an investigating doctor working for the forensic laboratory, is sleeping as his 16-year-old sister Eleanor watches:

His head had flopped to one side and the thin neck, stretched so still that she could see the pulse beat, looked too fragile to bear the weight of his head. His lips were slightly parted, and she could neither see nor hear the thin whisper of breath. As she watched he suddenly opened sightless eyes, rolled them upward, then closed them with a sign and fell again into his semblance of death.

“Small, wrinkled fists”

A few pages later, another child, a two-month-old baby named Debbie — the daughter of Susan Bradley and her husband Clifford, a biologist at the forensic lab — has her moment in the gentle spotlight of James’s story.

It’s half past six, and Debbie has started to wail. Susan moves quickly so as not to awaken her husband.

She picked up the warm, milky-smelling cocoon and crooned reassurance. Immediately the cries ceased and Debbie’s moist mouth, opening and shutting like a fish, sought her breast, the small wrinkled fists, freed from the blanket, unfurled to clutch against her crumpled nightdress…

Susan raised her cheek from resting against the soft furriness of the baby’s head. The small, snub-nosed leech latched onto her breast, fingers splayed in an ecstasy of content.

Yes, this is a scene in which the reader learns the Clifford Bradley is terribly scared of his boss at the lab, frightened that he will lose his job. This is a plot element among dozens of other plot elements.

Humane touches

But the description of Debbie, like the description of William, isn’t about moving the puzzle-solving along. Neither plays any role in Dalgliesh’s detective work or his piecing together of who did what when.

Yet, there they are in the pages of this James novel, just two glimpses into the humanity of the people who make up her story.

Dalgliesh does solve the crime — well, crimes — that have taken place in and around the forensic lab. But that’s not why you read a James novel like this.

You read for such wonderful humane touches, as the description of William asleep and of Debbie nursing.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.2.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.