Christopher Moore is a writer of joyfully goofy and ribald novels about such things as vampires, demons, San Francisco, a Native-American trickster and the comic aspects of Shakespeare’s tragedies, such as the randy fool in King Lear.

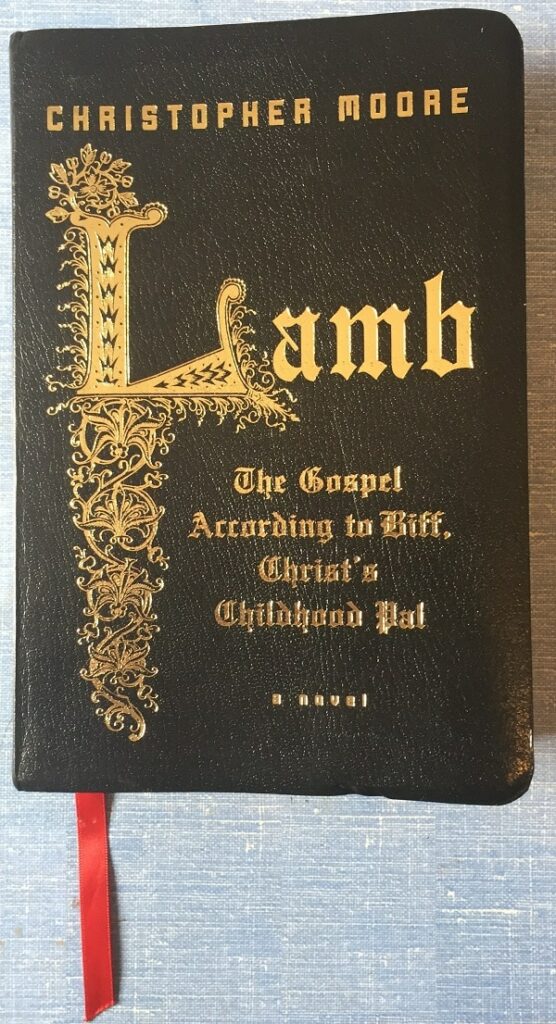

Yet, as much as it might seem a sacrilege to make fun of the Bard — Moore even has a novel called Shakespeare for Squirrels — he really swung for the blasphemy fences with his 2002 Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal.

Prior to this year, I’d read Lamb twice and reviewed it once, in 2017, reveling in its over-the-top irreverent humor with an undertone of seriousness.

That’s what’s apparent in all of Moore’s books. He’s cheeky, rude, mocking and profane, but his heart’s in the right place. His characters live in a world of darkness and threat, pain and violence, yet they find with each other hope and love and delight.

In 2018, Moore published a noir novel, called, surprisingly, Noir, which was sad and daffy and wacky and surprisingly heartfelt, but not all that dark, and not at all hopeless. In an afterword, Moore acknowledged:

“What I ended up with is essentially ‘Perky Noir,’ a lot closer to Damon Runyon meets Bugs Bunny than Raymond Chandler meets Jim Thompson…But what was I going to do? ‘Noir’ was already typed at the top of every page.”

Drudges and Excretions

Re-reading Lamb again recently (for a book club meeting), I was less struck by Moore’s humor than by his earnestness.

Part of this, I’m sure, is that I’ve heard the book’s jokes before, such as Biff’s tendency to prove a point by quoting from a non-existent biblical book, to wit:

- Dalmatians 9:7

- Imbeciles 3:7

- Drudges 5:4

- Excretions 3:6

- Amphibians 5:7

I realize that might not seem like thigh-slapping comedy to many people, but, for anyone like me who has spent a lifetime hearing references to this or that, often obscure, verse in this or that, often obscure, book of the Bible, it’s hilarious. Take my word.

“Around corners”

Most of the humor arises out of the idea that Jesus, whose name is actually Joshua in Hebrew, had a best friend. Well, why not? Why would Jesus have been any different from other kids?

And, like many best friends, the two are very different. Joshua knows — his mother’s told him more than enough times — that he will be the Messiah, but he’s constantly trying to figure out what he needs to do to fulfill that destiny. He’s studious, compassionate, responsible and more than a little obsessed with sex, mainly because he knows — the angel Raziel has told him — that he’s not supposed to engage in it.

Biff — well, Biff is different.

My proper name, Levi, comes from the brother of Moses, the progenitor of the tribe of priests; my nickname, Biff, comes from our slang word for a smack upside the head, something that my mother said I required at least daily from an early age…

My ability to learn Hebrew and the Torah was spurred on by my friendship with Joshua, for while the other boys would be playing a round of tease the sheep or kick the Canaanite, Joshua and I played at being rabbis, and he insisted that we stick to the authentic Hebrew for our ceremonies.

That’s more fun than it sounds, or at least it was until my mother caught us trying to circumcise my little brother…Overall, I think it was good for little Shem. He was the only kid I ever knew who could pee around corners. You can make a pretty good living as a beggar with that kind of talent. And he never even thanked me.

Brothers.

“Doofus”

Biff, as you can tell, is a smart-ass. I was going to say smart-aleck, but that’s too genteel. Biff ain’t genteel.

Biff has an anarchist’s affection for backtalk and subversiveness and a deep and abiding loyalty for Joshua who, while not a prig, is somewhat innocent and naive. Banned by the angel from sex, Joshua pesters Biff for descriptions of his many sexual encounters. It’s a kind of research.

From childhood, Biff and Joshua are friends with Maggie, Mary of Magdala. Biff loves Maggie, and Maggie loves Joshua. Of course, she also loves Biff, as a friend, which causes Biff no end of pain.

Biff smart-talks and back-talks everyone, including Joshua, and, at one point, when all three are 13, Maggie tells him:

“You shouldn’t make fun of him. He’s trying very hard….But aren’t you touched by who he is? What he is?”

“What good would that do me? If I was basking in the light of his holiness all the time, how would I take care of him? Who would do all of his lying and cheating for him? Even Josh can’t think about what he is all the time.”

“I think about him all the time. I pray for him all the time.”

“Really? Do you ever pray for me?”

“I mentioned you in my prayers, once.”

“You did? How?”

“I asked God to help you not to be such a doofus, so you could watch over Joshua.”

“You mean doofus in an attractive way, right?”

“Of course.”

A new gospel

Like the main characters in Moore’s other novels (all men), Biff is a Beta Male. He’s never going to be the hero of any world he’s in, but he’s trying to do the right thing and have fun and break some rules and take care of those he loves, Joshua and Maggie.

It’s that part of Biff that caught my attention in this re-reading of Lamb.

The book starts with Biff being awakened from the dead at the beginning of the 21st century by the angel Raziel. The powers that be, the angel tells him, have decided that it’s time for a new gospel and he’s the one to write it.

Lamb is this gospel that Biff writes with occasional glimpse of the St. Louis hotel room where he’s held captive by Raziel who spends all his time watching and not quite understanding television. They get their food and other deliveries from a Mexican bellboy named….wait for it….Jesus.

Biff’s gospel is in three parts:

- The childhood of the two friends, giving a lot more details than are now in the Bible, such as playing rabbis.

- The hidden years, which start when the two are teens and ends when they are 30 and which involve visits to the three wise men, from whom Joshua learns Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Hinduism, and Biff is schooled in the finer points of the Kama Sutra from various sexy women.

- The ministry and passion, basically the stuff in the four canonical gospels but seen from a slightly askew and more personal perspective.

“Even creeps”

Joshua learns a lot from the Far Eastern spiritualities as he’s trying to figure out his Messiahship.

For instance, on their way back to Judea, the two bump into an old friend in Antioch and visit over a cup of coffee:

Joshua was as excited as I had seen him in a long time. It might have been the coffee. “You won’t believe the wonderful things I’ve learned since I left here, Joy. About being the agent of change (change is at the root of belief, you know), and about compassion for everyone because everyone is part of another, and most important, that there is a bit of God in each of us — in India they call it the Divine Spark.

Joshua and Biff call it the Holy Ghost.

Despite Maggie, Biff isn’t a doofus. Or, at least, not only a doofus. He’s listening to Joshua and buying in to much of what he preaches. Indeed, Biff summarizes the gist of every sermon he ever heard from his pal:

“You should be nice to people, even creeps.”

Totally earnest

Christopher Moore describes himself as “a not particularly devout Buddhist with Christian tendencies.” His career has been as the author of sexy comedies.

Yet, when Moore’s writing here about the lessons that Joshua is teaching — change and belief, compassion, and being nice to even the creeps — he’s being totally earnest.

He’s also earnest about the final week of Joshua’s life and how excruciatingly painful it is for Biff to watch his friend permit himself to be offered up like a lamb for the slaughter.

Joshua’s passion takes up the final 37 pages of the 402-page book, and, this time of reading Lamb, I found myself caught up in Biff’s increasingly frantic efforts to save Josh — frenzied, agitated and unsuccessful.

For reasons that become clear in the novel’s final pages, Biff knows nothing of what happened after the death of his friend on the cross. This is a specter that haunts Lamb from the first to the last page.

All he knows is that his friend died. For all of Biff’s humor, there is an undertone of sadness to his story.

Maybe I needed a third reading of the book to finally tune into its sorrow.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.1.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.