Andre Norton was at the very start of her career as a novelist in the early 1950s. By the time of her death in 2005 at the age of 93, she had published more than 200 novels, most of them science fiction and fantasy.

Her first science fiction book, Star Man’s Son, (later, better known as Daybreak: 2250 A. D.), was the first novel to imagine life on earth after a nuclear war, a subject that, ever since, has been addressed by probably hundreds of others as well as scores of movies and television shows.

While breaking such new ground, Norton had also learned from her predecessors, such as Robert Heinlein, the value of creating a story setting which could be used in more than one book.

Recycling a setting and often characters resulted in a series of novels that shared the same fictional universe. It saved time and energy and let the writer focus on storytelling without having to envision an entirely new situation. Heinlein had two series: Future History and Lazarus Long.

Norton had nineteen series. One major setting was the Free Trader’s universe in which Norton set a series of series — seven series totaling 24 novels. A series, though, could have as few as two titles, such as the Central Control series, Norton’s initial use of the strategy.

The Central Control series

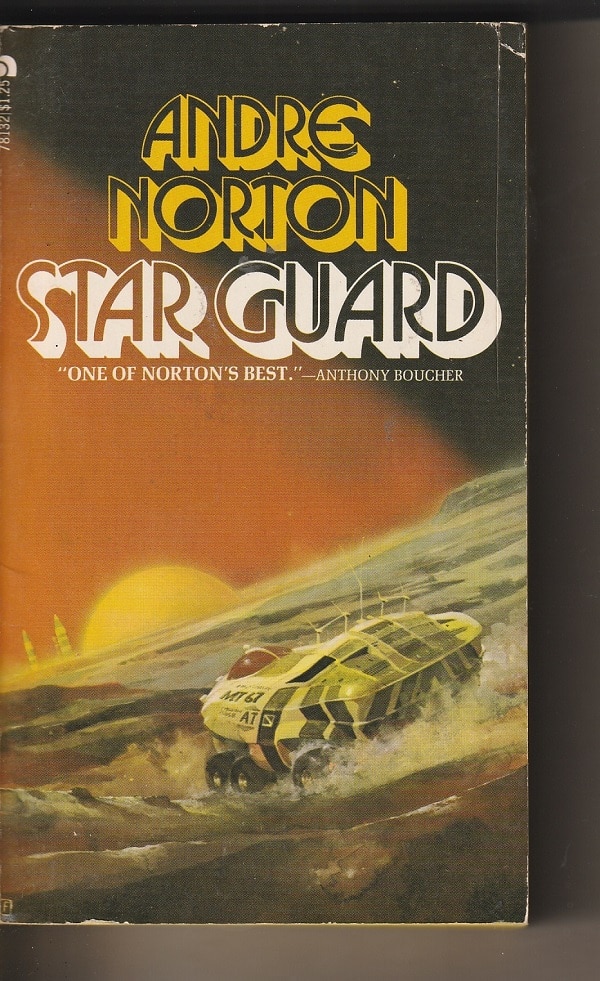

The two titles in the Central Control series were among the four novels Norton published in the three years following Daybreak: 2250 A.D. — Star Rangers in 1953 (later reissued as The Last Planet) and Star Guard in 1955. The Central Control books were set in a cosmos in which humans, late to the space travel game, had only the option of serving as mercenaries if they were to go to other planets.

I read The Last Planet a year ago when I was recovering from a bout with Covid. I found the story disappointing although it’s possible that the virus was the reason, not Norton’s book.

Star Guard is better but not as sharp as I’d hoped. And I’m thinking that maybe both novels are uneven because Norton was still learning her craft.

True, Daybreak: 2250 A.D. was a home run right off the bat for Norton. But it had a very tight, clear focus on the adventures of the young outcast Fors of the Puma Clan. The Last Planet and Star Guard are more episodic and involve a number of characters taking important actions, not just the central figure, lessening the story flow and coherence.

Like a western

That’s not to say that Star Guard doesn’t have its attractions.

Norton envisions two groups of Terran mercenaries, called Combatants: the Archs, experts in low-tech weaponry, who march in “hordes” and serve on low-tech planets; and the Mechs, experts in high-tech arms, who march in “legions” on planets with advanced technologies.

Because of powerful Central Control figures pulling strings in the background, these two end up pitted against each other on the planet Fronn in violation of 300 years of tradition and usage. There is no way that the Arch horde in which the new recruit Kana Karr is serving can go up against Mech power head to head, but, like many guerilla operations, they use their mobility and ability to work with the planet residents to accomplish their goals.

If you think about it, that sounds like the battle strategies employed by Native Americans against the European and later U.S. invader, and there is much of Star Guard that brings to mind western novels and movies.

For instance, you can almost see John Wayne leading a ragtag group of soldiers across a western desert, on the lookout for a larger and dangerous foe. (In this case, it’s the Native Americans who are the dominant force.)

The rugged country about them might be a lunar landscape in their own system, lacking all life. It was when the dried stream bed they followed branched into two that Bogate called a halt. Both of the new canyons looked equally promising, though one angled south and the other north. The Terrans, shivering a little in the bite of the wind from the snow peaks, were undecided.

How many times has a vista like that been shown in an American western movie? Indeed, the area is even called the badlands. And there’s something akin to tumbleweeds.

The wind was rising in gusts which whistled eerily between the heights, propelling the migrating puff balls — circular masses of spiky vines which traveled so until they found water where they could root for a season. Of a sickly, bleached, yellow-green, they were armed with six-inch thorns and the Terrans granted them the right of way.

“Give Grace”

The most affecting scene in Star Guard comes when Kana finds a severely wounded Arch named Deke and is told that the Mechs have ambushed his party of leaders sent under a white flag. Having delivered his message and too wounded to survive, he says to Kana, “Give Grace, Comrade—”

Kana swallowed, his mouth dry…He had been drilled in the ritual, he knew what had to be done….

Deke’s pain-filled eyes held his. His duty done, he was waiting for the release from the world of agony which held him…

Kana opened his shirt to find the slender knife that all Arches wore for just this purpose — the “Grace” of the fighting man. He said the proper words and then replied to Deke’s request: “— so do I send thee home, brother-in-arms!”

And ended Deke’s agony.

Star Guard may be a flawed novel, but that is a very poignant scene.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.23.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.