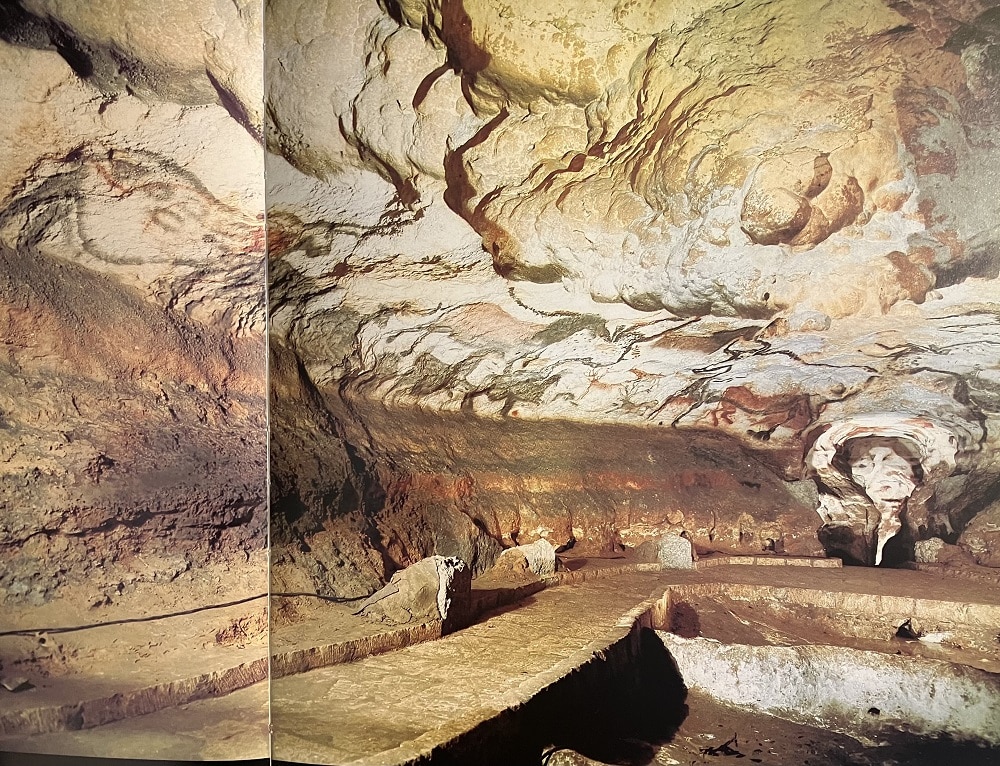

It is astonishing to turn to pages 102-103 in Mario Ruspoli’s The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs and find the curving wall and mural in the Hall of Bulls, also called the Rotunda.

Part of this is the way the photograph is laid out over a page and a half, with the fold separating a quarter of the image on the left from the three-quarters on the right. This gives a curve to the pages as they each lift away from the fold, a curve that echoes, in a way, the bend of the wall, from left to right.

But, mainly, the amazement comes from the beauty and richness of the art, from the rhythm of the figures moving toward the opening that leads to the Axial Gallery, a procession of animals in action in unison.

And that these images, discovered in 1940, were created by an artist or artists some 17,000 years ago.

That’s roughly 50,000 human lifetimes ago.

Two processions

Not in the photograph is a similar procession of animals depicted to the right of the Axial Gallery opening, moving, in their case, from right to left. Both processions are headed for that opening, as if on migration.

The difficulties of photography in such caves means that it was impossible to get both processions into the same frame. Indeed, as happens in many of the caves that are found with prehistoric art, some images in the Lascaux cave system could not be photographed at all.

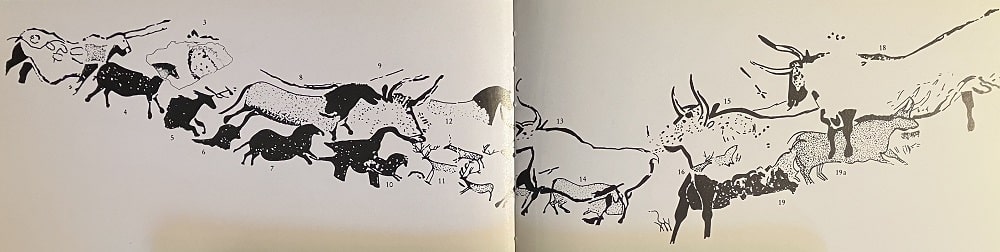

But Ruspoli does provide a drawing that replicates the two sides that make up the frieze.

Of the artists who produced such images, he writes:

Their beautiful and daring compositions have earned the cave the name “the prehistoric Sistine Chapel.”

Three books

The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs is one of three scholarly and lushly illustrated books published over the past four decades about the richest prehistoric cave systems that have been discovered so far.

One of the other books is The Cave at Altamira by Pedro A. Saura Ramos, published in 1998.

This cave system, near the Spanish town of Santillana del Mar, was discovered in 1868, nearly three-quarters of a century before Lascaux. It is believed to be about 14,400 years old, or a couple millenniums more recent than Lascaux.

Given the beauty of Michelangelo’s ceiling paintings and their fame in Western culture, it is no surprise that Altamira, like Lascaux, has also been called the Sistine Chapel of prehistoric art.

Arguably, though, the third cave system could be described as equally beautiful — and it’s more than twice as old as Altamira and nearly twice as old as Lascaux.

The Chauvet Cave, near the town of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in Southern France, contains art that was painted more than 300 centuries ago, carbon-dated to around 30,790 years ago and earlier.

It was found in 1994 by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps and Christian Hillaire, three recreational speleologists, i.e., people who search for and explore caves for scientific purposes, combining skills in fields of chemistry, biology, geology, physics, meteorology and cartography.

In their book, Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave — The Oldest Known Paintings in the World, published in 1996, the three write about their initial search of the cave system and how it felt to come upon the Lion Panel with its overlapping portraits of nearly a dozen big cats advancing leftward across the rock wall toward a crowd of bison and other animals:

Suddenly our lamps lit up a monumental black frieze that covered 30 feet of the left-hand wall. It took our breath away as, silently, we played our torches over its panels. There was a burst of joy and tears. We felt gripped by madness and dizziness.

The discoverers of the Chauvet Cave lay claim to the title “Dawn of Art,” but, in truth, all three of these cave systems represent together the beginnings of human artistic expressions.

The artists here, in these three places, belong with the ranks of Leonardo da Vinci, Georgia O’Keefe, Michelangelo, Artemisia Gentileschi, Vermeer, Giotto, Manet, Mary Cassatt, Monet and all the other modern (i.e., since maybe 500 A.D.) painters whose work pack our museums today.

If it weren’t for the fragility of these cave systems, they would be major pilgrimage sites of art lovers from across the globe.

A television series and a book

Ruspoli was a filmmaker who was chosen by the French Ministry of Culture to create a video record of the paintings and etchings in the Lascaux Cave. The recordings, conducted under strict guidelines, took place over a three-year period and were the basis for an eight-hour, four-part television series Corpus Lascaux in 1983.

Afterward, Ruspoli created The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs, a large-format book centered on scores of still images that were taken as part of the film project.

These, he wove into a deeply researched text which went into great detail describing the Magdalenian Civilization that produced the cave paintings as well as the animals with which the people of that era lived, how those people hunted, fished and gathered, and the indications that have been found of the religion of those people and their language.

When the book was in final production, Ruspoli died suddenly on June 13, 1986. The work was published on May 4, 1987.

Art as religion

In describing what he and his film crew found at Lascaux, Ruspoli writes:

The Palaeolitic artist were certainly not consciously making art, and they had no idea of preserving it.

They were intent only on fixing momentarily — sometimes using very elaborate techniques — the images of a religious and mythological world in which the elements recur of what could be called a first Genesis, resulting from the relationship between mankind and the deified animals.

In the imaginary space, magic and metaphysics are expressed by the interplay of symbols based on tradition, as in primitive religions.

In other words, the paintings and etchings on these walls weren’t art for art’s sake.

They were expressions of religious beliefs — beliefs that Ruspoli rightly notes that are impossible for us to determine from such a far distant time.

Art as art

So, for us, without the religious worldview of those artists, we can only look on these paintings and etchings with awe. We can only approach them as works as art — as a beautiful and skillful expressions of human beings responding to their world.

Consider the Fleeing Horse at the end of the Axial Gallery:

This image is an amazing evocation of strength, motion, beauty and effort at full gallop.

Similarly, this painting of the Great Black Aurochs, exhibiting power and, with its flowing hair, speed and intense energy:

By contrast, the Falling Cow, with a spear in its body, is the epitome of distress. The image communicates agony, uncertainty and a wobbling and a stumbling:

Rhythms of the herds – two more processions

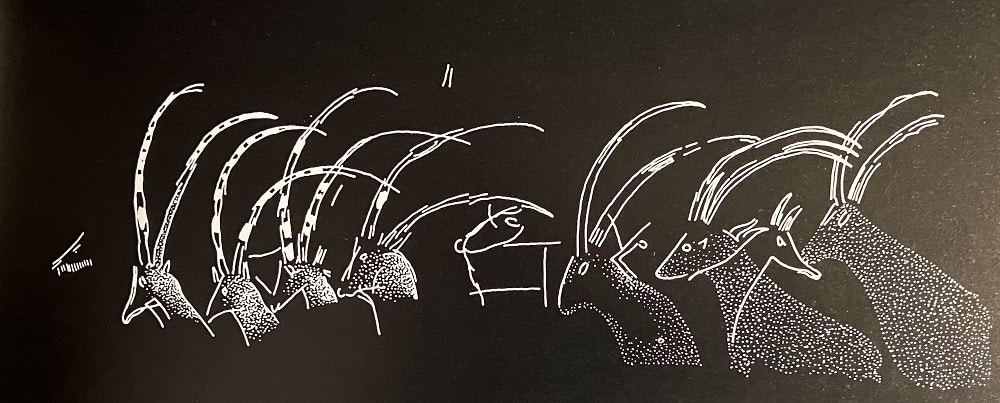

Engravings on stone are difficult to photograph in most cases, but especially in these ancient caves with their rough walls and difficult lines of sight.

Ruspoli solves that problem by offering the reader a transcription of one — a line of seven ibexes with their long curved horns, crossing each other here and there to give the sense of the individuals moving or standing together in a herd.

There is a similar yet different rhythm to this grouping of swimming stags that were drawn quickly with a manganese crayon in an area called the Nave.

In this image, the artist used the dark color of the lower rock to represent the river in which the deer are swimming. Ruspoli writes:

Only the necks, heads and tall charcoal antlers are visible; the rest of the bodies vanish into a mass of dark, misty rock, which forms the “imaginary ground,” or rather the “imaginary river”…..

The coarse yet precise quality of the line does not detract from the magnificent drawing. The movement of the swimming herd recalls the fords that were regularly used by deer and this gives the procession of animals the sense of being documentary evidence taken from life.

The masterpiece

The masterpiece of Lascaux is the image that is hidden at the farthest point, at the bottom of a shaft that Ruspoli describes as a “sacred place…the heart of the sanctuary.

One experiences a sort of metaphysical shock and begins to speak in a hushed voice, almost a whisper, while the light travels along the vertical walls and suddenly reveals the famous scene.

There is the bison, its entrails hanging out, its tail lashing the air in rage. A long spear cuts across it. The bison has two manes, a device used by the artist to signify the movement of the animal as it lowers its head to gore its enemy.

That enemy is the man, a puppet dressed up in a bird mask, thrashing about with arms that are almost as spindly as his legs, with only four fingers on his hands. He is falling backward with the stiffness of one consenting to his own murder — and so reestablishing the order of nature.

Ruspoli writes that this image, given its quality and its narrative and its location, obviously had some strong religious import for the artist and anyone of that era seeing it, that we can only guess at.

For us, today, perhaps reverence before the artistic richness is the best and only response.

And the best and only response to the art at Lascaux as well as at Altamira and Chauvet — to the genius of artists of 100,000 human generations ago.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.9.2023

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.